Arizona has become the site of a little-noticed literary flowering: it is home to some of the best prison writing in North America. During the last two decades, Jimmy Santiago Baca, Ken Lamberton, and Richard Shelton have converted their experiences with Arizona’s penitentiaries into prize-winning books. No US state can claim a similar cluster of prominent prison writers. Baca has become one of the major voices of Chicano literature; Lamberton writes luminous nature essays and has won the Burroughs Prize; and Shelton’s Crossing the Yard (University of Arizona Press, 2007) is the much-noticed autobiographical capstone of a 30-year career as a volunteer teacher in prisons.

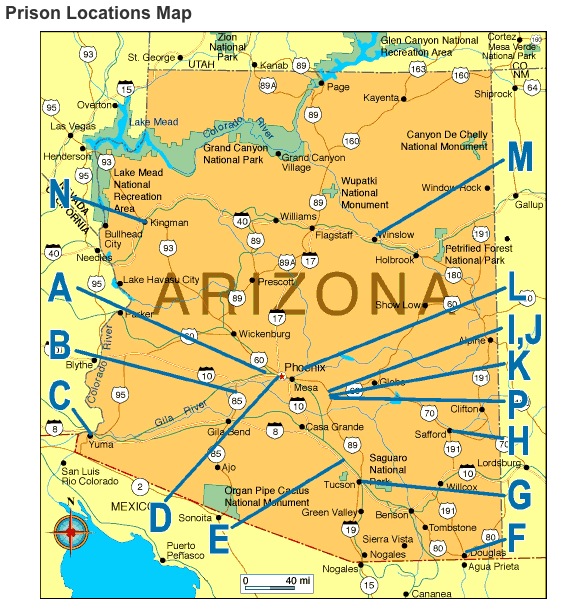

The carceral state birthed an incarcerated literary movement. Conditions were ripe for a take-off. For comparison, Arizona prisons currently hold over 40,000 inmates, or about twice the number in Australian prisons despite Australia having three times the population. The state’s repressive civic climate keeps adding to that number for much the same reasons as Arizona’s criminal law system long has served as an out-sized source of civil rights decisions from the federal courts. In Arizona, there is no social problem that a stretch in county jail or state prison cannot be recommended to solve. One in 33 citizens is incarcerated, on parole, or on probation. The prison industry cannot find enough Arizonans to jail, so the state’s private prisons now hold most of Hawaii’s prisoners and tens of thousands of undocumented immigrants.

Walking Rain Review, one of the centerpieces of this literary movement, has been a witness to this build-up of Arizona’s prisons. Richard Shelton, a now-retired English professor and distinguished poet who made his career at University of Arizona, founded the journal twenty years ago to publish the work of inmate writers from Arizona prisons. Fifteen issues ensued. Many of the writers appearing in the journal participated in the creative workshops that Shelton led for decades.

The 15th number of the journal, published last year, will be the last. It is unfortunate that the journal is closing down, but such journals are labors of dedication that fade away together with human energies that have created and maintained them. Ken Lamberton and Erec Toso, both of whom have worked with Shelton, are planning a new prison literature journal to continue the work of Walking Rain Review.

Reading the poetry and prose, I come across the familiar voice of William Aberg. But he is the only one I know: all the rest are unfamiliar to me as writers. A small group of names appears from one issue to the next, a sign of a writing community that the review has encouraged and enabled. One expectation haunts this journal and prison writing generally: it should concern prison. But why? An imprisoned imagination nonetheless can take readers to vastly different landscapes and moods. This limitation of expectation burdens readers who have read little prison writing, not imprisoned writers. As much of the writing in Walking Rain Review makes no reference to prison as does writing that locates itself within prison.

Prison writing that is self-referential in terms of imprisonment raises another issue that has pursued critical theory for generations — the role of biography in interpretation. The interpretive schools of both New Criticism and deconstructionism emphasized the text by itself and rejected biographical information on the author, although for different reasons. Contemporary theory tends to be less prescriptive, suggesting that as readers we can and should use all information available to us while weighing it with good judgment. While we cannot read a poem exclusively through its author’s biography, neither should we ignore available evidence that facilitates textual analysis.

For example, take Gordon Grilz’s short poem “Rescuer” that appears this last issue. It reads, in part —

We sent out search parties

at first light but they found

no trace of you

only the empty place

where my wife used to live.

These lines echo with the bloody facts that 30 years ago Grilz, intoxicated, walked into his estranged wife’s home with two weapons, executed her male friend with three bullets to the chest and one to the back of his head, then put four more .30-30 rifle bullets into the head of his wife in the kitchen as she called the sheriff’s office. Their two children were in the next room. Who is the “you” in this line? Why does it begin with an omniscient distance from the subject? Who emptied his wife’s place and how? Is that “empty place” a double-entendre? An absence of biography acts to conceal, not reveal.

This history calls into question the ethics of another Grilz poem, “Arbeit macht frei,” with its implicit comparison of Auschwitz prisoners to the “we” of contemporary prisoners. Did Grilz hear the irony of this poem’s opening line?

The guard in the tower looks

down on us. He stands

silhouetted against an

overcast sky choosing

his targets. The weight of

the rifle on his shoulder is

nothing compared to the burden

of his soul.

The poet held a rifle and fired, not the poem’s guard. A poem cannot take back and redeem murder. Ethics lie in acts, not ruminations. False victimization via a poem only compounds prior acts.

Yet even if a poem such as “Arbeit macht frei” can be challenged for a very poor analogy that suggests one writer’s continued denial decades after these acts, much of the work suggests intense engagement with memory. In a compelling poem entitled “Something Inside Me,” James Anderson writes —

I was released from that prison one year

and nine days ago, but last night

remembering, I sank

deep into the terror

that curls claws beneath my chest,

trembles me like water boiling,

boiling, boiling…

Anderson’s exact time-keeping from his release date and his Poe-esque invocation of terror suggest how imprisonment haunts consciousness. Once imprisoned, in a deep psychological sense always imprisoned. On the facing page from this passage, Stewart Gonzales details the methodology of psychological damage in “Strip Search.” Guards conduct the search —

With eyes like x-acto

Knives peeling me

Layer by layer

Until I am nothing

They feel more secure

Knowing I’m not hiding

My dignity in any

Cracks or crevices

The William James Association has documented and fought against the continued elimination of arts programming in US prisons. Yet even as US state prison budgets continue to grow, overtaking state expenditures for higher education, prison education and arts have been chopped mercilessly. In California, the Pelican Bay super-max prison ran an excellent literary journal that printed its last issue two years ago. It is journals published outside the walls that are sustaining US prison writing.

We need forums such as Walking Rain Review to read and debate prison literature. There is a sense of profound loss when such a journal disappears. In the context of constantly disappearing educational and communication opportunities in prisons, it is a loss that strikes both inmates and a public readership. The social concealment of the vast US prison system advances a small step instead of retreating.

One is always astonished at Joe Lockard’s range of knowledge and the ardour with which he fights for the literature of the underprivileged , he is prominent for his courses on anti-slavery literature , it is always fascinating to follow his insights into paths of American writing.

More from that author !