Today, the media spotlight is on Philip Hammond as he tries to steer away from disaster and reassure the British public that the Conservative government might be worth keeping around. But the truth is that the Autumn Budget is boring and it was intended to be. What matters much more than the budget is the history in which we are living.

It is easy to forget that we are living in just another chapter of human history. Francis Fukuyama was wrong to suggest that the historic conflicts of ideology were a thing of the past because we had reached the final stage: liberal democratic capitalism. Yet more than a quarter of a century later, the West finds itself confronted at every front by new populist challengers.

The recrudescence of nationalism with Brexit and Trump should remind us that the past is always with us. Another reminder is the way that the old leaders keep popping up, whether it be George W Bush or Tony Blair. It’s always funny to see past leaders resurface many years after leaving high office.

Most recently former PM Gordon Brown has been on the airwaves and our screens describing Jeremy Corbyn as a “phenomenon”. He’s been out of power for several years now and he usually refrained from talking about the Labour leadership, though we should not doubt that Brown was not a friend to Corbyn in the past.

The former PM was one of the New Labour grandees to come out and attack Corbyn’s candidacy on the campaign trail. Brown threw the kitchen sink at JC, bringing up everyone from Putin and Chavez to Hezbollah and Hamas. It was a hysterical speech of epic proportions. Yet this is not the approach Brown takes today.

Instead Brown argues that the party has to unify around Corbyn because it is clear the Labour leader speaks to the British public and addresses their concerns. But this is a tactical position and it should not be misread. Brown wants to see to it that the Labour right survives in the long-term, and the best way to do this is to cooperate with the Corbyn project of mass party democracy.

If there is a real difference between the Blairites and the Brownites, it is over tactical questions. Brown was always more cautious than Blair and this sometimes took the form of interesting splits on policy. For instance, Blair was so passionately pro-European that he backed the euro but this was opposed by Brown and his allies. Likewise, the Brownites were much more sceptical when it came to unleashing market forces and did so to the extent they felt it was the most practical choice.

The difference is pragmatism, though the aims and many of the methods remain the same. Indeed, it should be understood that Brownism is just a sub-section of Blairism. It is wrong to claim that the Brownites were to the left of the Blairites because the two groupings occupied a very narrow conception of political ideas and debate: the radical centre.

Oxymorons aside, the Brown government may have been a brief detour away from the Blair years in its loss of style, however, the substance remained the same. It was New Labour with bad PR, and the fall of the Brown government was really the end crisis of the Blair legacy and Corbyn may be the answer. This process mirrored a similar crisis in the Tory Party after Thatcher was forced out of power. Except it has no answer.

The ousting of Thatcher in 1990 left a deep void in the Conservative Party, which has never been totally surmounted. The first attempt was to propel Major into its entry. The first problem was that the Conservatives had to redefine its agenda in time to win another election. At first, the Major government moved to initiate market reforms in the public sector mainly in the form of performance targets. Once this failed, Major turned to ‘back-to-basics’ moralism about single parents and other manifestations of ‘public indecency’.

Despite the recession, John Major held strong in 1992, and the Labour Party was once again defeated. Much like Miliband, Neil Kinnock had attempted to avoid deviation from the acceptable lines of debate. He had capitulated at every turn and hoped to bypass the most pressing political issues of the day. As bad as the Conservative establishment was, in the eyes of most people, at least it was clear where they stood. Likewise, Miliband failed to assert a counter-narrative to the dogma of austerity, thereby disarming the opposition.

The reality of the situation in 1992 was only realised five years later. John Major had won because he was effectively unchallenged, but the silent crisis in the Conservative Party became increasingly vocal. It soon erupted in a rebellion of backbenchers against the leadership and its conditional support for the European project. Major stood little chance against Tony Blair, who easily out-manoeuvred the decrepit government. The void at the core of the Tory Party still remains. It is ever present in Downing Street under this government.

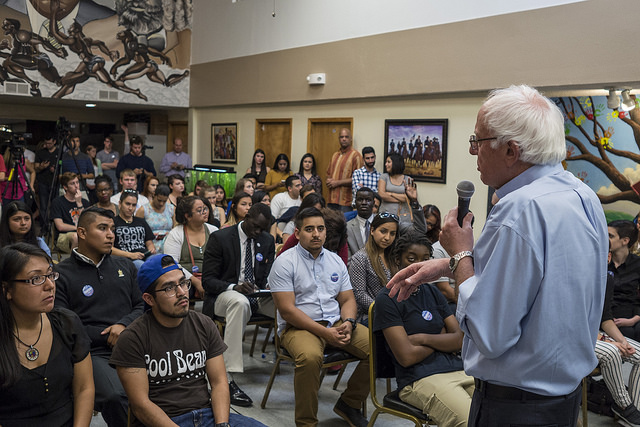

Photograph courtesy of Matt Brown. Published under a Creative Commons license.