“Lippy Kids”, the strongest track on Elbow’s latest album Build a Rocket Boys!, takes a while to build up momentum and even longer to ease to a close. Over the sparest possible piano figure, a single note played over and over, simultaneously insistent and muted, a series of tasteful accents is gradually added and then subtracted. Only the carefully spaced intrusion of Guy Garvey’s evocative voice imparts the weight of a full-fledged song. Even then, the music sounds like it’s about to evaporate, making the six-minute running time something of a miracle.

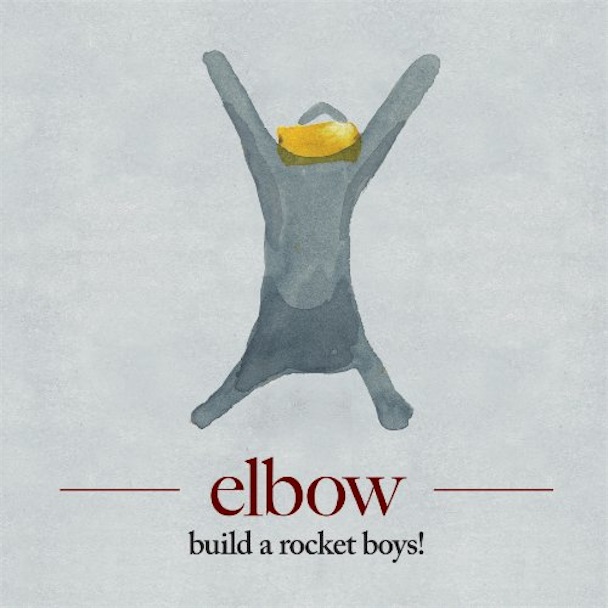

This sense of fragility suffuses Build a Rocket Boys!, whose bold title seems like an ironic commentary on the band’s reluctance to make grand, reckless gestures. Garvey’s lyrics impressionistically communicate the splendid messiness of boyhood, but with the wistfulness of someone who can only remember what it felt like instead of feeling it anew. While Elbow has never been the sort of band either to indulge or inspire bacchanalian abandon, their subject matter this time around confirms how completely they have rejected the commonplaces of youth culture.

Elbow isn’t alone in this regard. Indeed, a number of the artists most lauded by contemporary critics make music that refuses to rock or roll. From the gentle neo-folk harmonies of the Fleet Foxes to the post-classical minimalism of Sufjan Stevens, from the dub-haunted soundscapes of Burial to the pulsing tableaux of Radiohead, a large swath of popular music seems intent on repudiating distinctions that have been taken for granted since Sun Records introduced Elvis Presley to the world.

Despite what the more myopic devotees of Radiohead might think, the idea that rock musicians might transcend their genre through sheer force of will and talent is nothing new. After all, it was in the 1960s that rock and roll metamorphosed from youth entertainment into an art form worth taking seriously. At least, that’s how people who wanted to take it seriously have told the story.

That said, there’s no shortage of examples with which to prove their point. Bands like The Beatles, The Beach Boys, The Kinks and The Who all moved from writing music that made teenagers shriek and writhe to the sort that invited rapt contemplation, simple two-minute pleasures giving way to architecturally intricate suites adorned with details even FM radio technology was too crude to communicate. Even when these latter works still “rocked”, to use the vernacular parlance, they did so with a self-awareness that made listeners believe that their too-solid flesh could melt into air.

Coupled with the way Pop Art, following Marcel Duchamp’s notorious lead, recast throwaway goods as gallery fare, this trend inspired a massive legitimation crisis in the domain of culture. Suddenly, the developmental narrative that had implicitly underpinned taste-making was broken into fragments that could be arbitrarily rearranged like episodes in a Modernist novel. It was still possible to grow out of a particular preference, but doing so was no indication that one had grown up. Indeed, maturation could be signaled by abandoning prejudices against mass culture for an anything-goes mentality.

More than four decades later, the effects of this stunning reversal are still keenly felt. To be sure, there are some who make the passage from youth to adulthood in a linear progression, leaving behind one set of taste preferences for another at each stage along the way. But whereas these individuals would once have been typical within educated circles, their insistence on putting the past behind them now marks them as eccentric.

Ever since the Baby Boomers began to feel middle-aged, it has been considered perfectly normal to stay fiercely attached to one’s youthful infatuations. In his 1982 song “Jack and Diane”, John Cougar famously urges listeners to “hold on to sixteen as long as you can”, because the burdens of being a grown-up are just around the corner. As the large number of twenty and thirty-somethings still living with their parents indicates, a lot of people have taken this injunction literally. But far more have heeded this advice in their cultural pursuits.

Critics often lament that the majority of today’s Hollywood movies are targeted at teenagers, with little funding left over for pictures with “mature themes.” What this argument overlooks, however, is the fact that it’s not just teenagers who flock to films heavy on special effects and light on story. On any given night at the multiplex, a sizable percentage of the people attending such fare will be middle-aged viewers who have opted not to act their age.

The same phenomenon manifests itself in popular music. That balding guy blasting “Nuthin’ but a ‘G’ Thing” from his hybrid SUV at a stop light, the wool-suited lawyer who buys a compilation of early 80s alternative rock while getting her morning latté at Starbucks, the software engineer who schedules his vacation so that he can finally see My Bloody Valentine live at All Tomorrow’s Parties — all are doing their best to prove that one’s relationship with a cultural touchstone is never truly over.

This, in fact, is the reason why what’s left of the mainstream music business has placed so much emphasis on reissuing old records in “new-and-improved” guises. A great many consumers are more willing to buy music they already have for a second or even third time than they are to risk their money on something new. Demonstrating financial devotion to their past is a way of making it stay part of their present.

It’s against this societal backdrop that we must evaluate the work of bands like Elbow. For in rejecting the commonplaces of youth culture, they are also declaring their opposition to the mainstream. There’s no shortage of irony in this posture. Although they certainly aren’t known as a chart-topping act, Elbow’s last album The Seldom Seen Kid did win the prestigious Mercury Prize and eventually went gold in the United Kingdom. And Radiohead, with whom Elbow have a lot in common, have managed to parley their “outsider” status into top-ten sales around the world, including the United States.

But maybe we should stop thinking about the mainstream in such commercial terms. As ease of access to cultural diversity and a dearth of shared experiences make what Chris Anderson calls the “Long Tail” a major force in the marketplace, the fixation on youth is becoming a crucial common denominator. Whether mega-selling or niche-marketed, youth — not as an age, but a concept — is mainstream. At a time when we are constantly being bombarded with culture that is supposed to make us feel younger, it’s almost radical for art to insist that we act our age.

That’s why the most important track on Build a Rocket Boys! is also the one that people who cherry pick songs for their iPods are least likely to choose. A reprise of the album’s opener “The Birds”, it’s the only song that doesn’t feature Garvey’s expressive singing. As the lyric sheet explains, the man repeating lines like, “the birds are the keepers of our secret as they saw us where they lay,” in a wavering, gravelly voice is John Moseley, a now-retired piano tuner and professional actor who, “still finds time to play at home in Cheshire where he lives with his wife Audrey.”

Like the retiree Paul McCartney imagined in The Beatles’ “When I’m Sixty-Four”, Moseley is defined by his successful passage to old age rather than inevitably doomed efforts to stay young. As a role model, then — and it’s worth remembering that Paul McCartney is actually older than Mr. Moseley — he is a true alternative and also a testament to Elbow’s achievement. It may be hard to endure youth with grace, but surviving adulthood demands even more of us.

Build a Rocket Boys! is not a thrilling record. The responses it inspires are sedately ruminative. Yet in forcing us to ponder our expectations for rock and roll, the tacit assumption that music can temporarily free us from the burdens of history, it provides us with satisfactions of another order. Sometimes it’s better to fade away slowly than to burn out before we’ve taken the measure of our times or ourselves. Because the real miracle is not in finding the fountain of youth, but perceiving the beauty in losing it.