It was my friend Jerlyn who got me into hardcore punk. We went to high school together. At the time, I was a wayward ex-raver looking for something — anything —with a drop of integrity. I was around sixteen when I went to my first hardcore show.

Punk felt familiar. Everyone was a reject on some level. Hardcore kids were earnest and messy, unpretentious on principle, though sometimes to the point that sincerity became its own pretension. They flaunted their awkwardness and reveled in their youth. Popularity was petty and scorned. They dressed androgynously, everyone in the same work pants and plain t-shirts, and played together like brood of puppies, childish and pack-like.

Fast-forward ten years. I survived high school, went to college. I moved to Israel. In Jerusalem, I completed a Master’s degree in Cultural Studies and wrote a thesis on a religious revival there. After a few years, I moved back to the States and ended up in San Francisco. One night, I was making dinner with a friend in Oakland, clicking through old punk clips on YouTube between chopping vegetables.

“You know that band Shelter?” He was frying onions in an iron skillet. “They sing about Krishna consciousness and shit. I used to think they were sketchy back in the day, but I just heard them on Pandora — I kind of like them!”

We googled “shelter hardcore band” and found their old albums covers, replete with frolicking Hindu deities mixed with golden goddess statues under names like “Perfection of Desire” and “Attaining the Supreme.” The old singer had taken on a Sanskrit name and was now a yoga teacher in Greenwich Village. The picture on his website showed an upside-down tattooed body balancing on one hand, his legs bent in complicated geometry.

This brought back blurred teenage memories of going to a Krishna Temple with Jerlyn and her boyfriend. There was a ceremony and then a free vegetarian buffet. I remember one or two hardcore kids in their Dickies and Salvation Army dress shirts sitting outside in the balmy Detroit summer eating dal and curried potatoes, wooden bead necklaces and thin canvas shoes. Hare Krishna hardcore punk? Although I’d forgotten the idea for a long time, it still felt familiar somehow.

I became fascinated and curious over this lost chapter of punk history. When I had been working on my master’s thesis in Cultural Studies, I became interested in the anthropology of alternative spiritualities, what scholars refer to as new religious movements. New religious movements flourished in the West after the 1960s. Everything from the Jesus People to Family International, from Sufi clowns to the Hare Krishnas, drew adherents from the countercultural milieu. Although the original counterculture was rooted in the antiwar movement, and implied a range of radical causes, some of its successors left behind the political critiques in favor of spiritual ones. Others found a way to interweave political and spiritual ideas, with many unexpected results.

I began to wonder about other new religious movements and how they interacted with countercultural values. Punk is one of the only widespread youth subcultures left (the other than comes to mind is hip-hop) that still maintains a radical political stance, however nebulous and unrefined. Krishnacore appeared to interweave punk with an alternative spirituality. “How does that work?” I wondered.

II. Origins and Evolutions

The International Society for Krishna Consciousness, or ISKCON for short, was founded in 1966 by A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Prabhupada was a renunciate in the Gaudiya Vaishnavic tradition that dates back to the 16th century. The Hare Krishna movement, and the term for its adherents, comes from the Maha Mantra, or “Great Mantra,” whose repetition is believed to bring about “Krishna consciousness,” a higher consciousness expressed as a pure love of Krishna. Their primary text is the Bhagavad Gita and the Bhagavata Purana. Their central practice is the devotional worship (bhakti) of the gods Krishna and Radha (Krishna’s consort, a godly name for a girlfriend). Krishna is viewed as an incarnation of Vishnu, the supreme God. The iconography is elaborate and the terminology esoteric and exhaustive, drawing from the many worlds of Hindu philosophy.

Prabhupada traveled to the United States in 1965 intent on spreading Krishna consciousness in the West. The story goes that he came with only forty rupees, roughly seven dollars, and lived off the profits of the literature he sold on the street. Prabhupada would sit in Tompkins Square Park chanting under an elm tree. The hippies hanging out around the Lower East Side were naturally drawn to the swami singing under the tree. Before long, they began to sit and chant with him. After only two months, he had cultivated a following. He encouraged the young people to preach, dance, and sing as a way to spread the word. The elm tree under which he sat is today called the Hare Krishna Tree, complete with a plaque and an inscription. According to the plaque, it’s the first place Prabhaupada chanted the matahare chant in the United States.

The group established a headquarters in New York City in the 1960s and another center in San Francisco soon after. The organization grew quickly. ISKCON opened a temple in Detroit in 1975 at a mansion on the Fisher Estate where I would go to vegetarian buffets twenty years later. The property was bought for the organization, strangely enough, by Elisabeth Reuther Dickmeyer and Alfred Brush Ford. Dickmeyer was the granddaughter of Walter Reuther, president of the UAW until his mysterious death in a plane crash 1970. Ford is the grandson of Henry Ford. He had become a Hare Krishna in 1975 and renamed himself Ambarish Das.

For most of their history in the United States, the Hare Krishnas were viewed as a cult by the mainstream. The movement and eponymous chant became associated with drugged out hippies; it’s even in Hair. This is ironic considering that the regime of “the four principles,” corresponding to the four legs of dharma, forbade intoxicants and casual sex, making any serious overlap with the hippie counterculture limited at best. While the group was the target of anti-cult task forces, academics argued that Hare Krishnas were not a “cult” but, to the contrary, a proper “religion.” The Hare Krishnas were practicing Hinduism as it had been practiced for centuries, they said.

Nonetheless, there were several scandals and trials against the organization starting in the mid-1970s, picking up steam after Prabhupada’s death in 1977. By the late 1980s, the movement had begun to contract, its followers defecting to practice on their own or with different gurus in similar Vishnaic traditions. The worst came in the late 1990s when over ninety accusations of child sexual abuse were leveled at ISKCON boarding schools in India and the US. In spite of these scandals, the group remains viable. It has developed a presence in the former Soviet states while its following in India continues to expand.

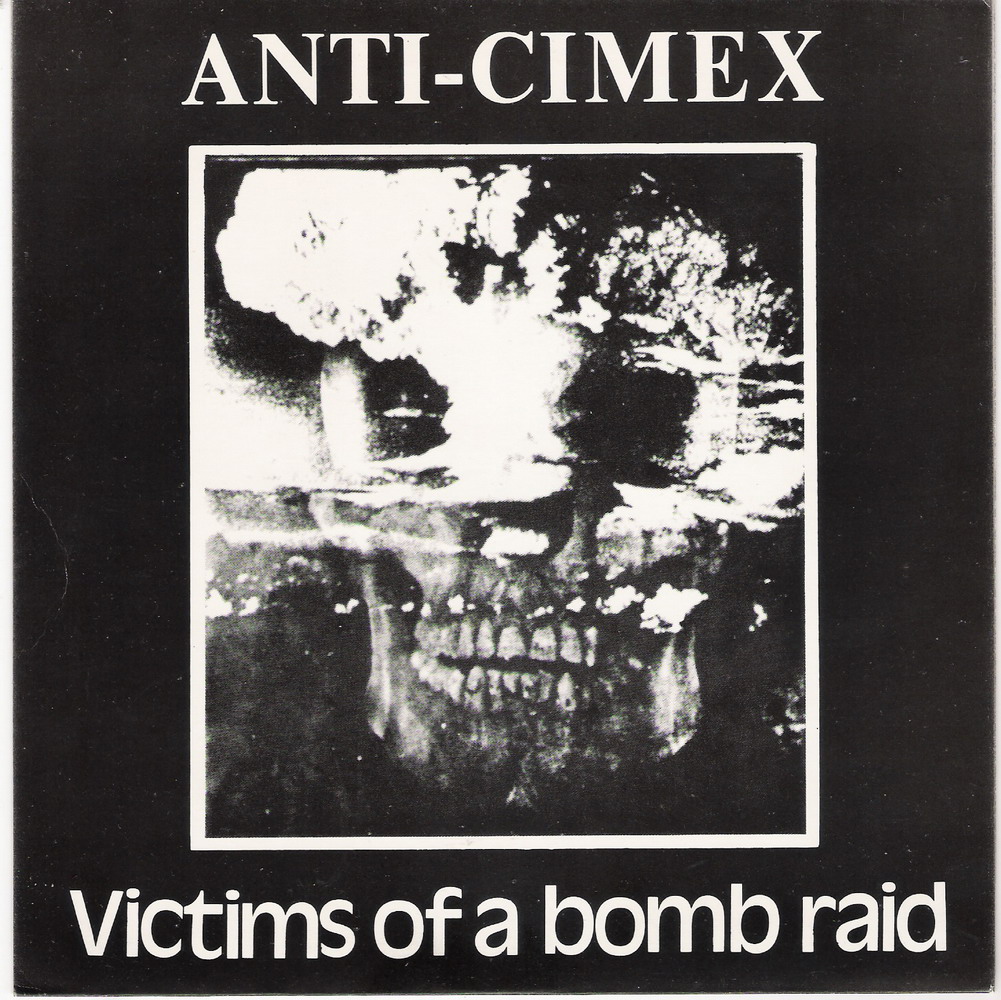

The historical memory of punk is shoddy at best, left to gonzo journalists and oral historians. The “straightedge” lineage of hardcore is unique in this respect. It can be traced back to one song by Minor Threat, the punk band from Washington, DC, fronted by Ian McKaye who would later form Fugazi. In the song “Straight Edge” McKaye derides people for smoking dope, eating pills, and sniffing glue. “I’ve got the straight edge,” he sings in the chorus.

Straightedge became the term for swearing off drinking, drugs, and casual sex. The letter “X” — simple, crude, defiant — became the symbol of straightedge. What had started as the mark the doorman put on underage kids’ hands so the barman would know not to serve them at shows became a badge of sobriety. It was a way for both the underage and “legal” alike to declare that they were rejecting the lifestyle that made this designation necessary in the first place.

Somewhere around the late 1980s, hardcore became nearly synonymous with straightedge. Hardcore originally referred to the style of music that was faster, heavier, and more discordant than other kinds of punk at the time. Vocals were shouted in a style somewhere between marching slogans and a yelling tantrum. Musically, it borrowed from heavy metal and thrash, moving away from the ska roots of early punk. Straightedge kids and older punks overlapped at first. But as straightedge gained momentum, the scenes began to diverge. Hardcore bands started touring with other hardcore bands and crowds mixed less.

In Straightedge Youth: Complexity And Contradictions of a Subculture, author Robert Wood quotes McKaye saying that the older punks thought the straightedge kids were “some weird fundamentalist Christian kids” or just plain stupid. Straightedge challenged aspects of punk culture that had been taken for granted. It made the link between the excesses of the origina punk scene and a society that goaded people to consume endlessly and distract themselves with mindless entertainment. Straightedge called out the nihilism of punk for the kind of apathetic self-annihilation that had been so glamorized in figures like Sid Vicious. Deviance and rebellion could take many forms, the straightedge kids were saying, not all of them self-destructive.

The Emergence of “Krishnacore”

There are conflicting creation myths surrounding the origins of Krishnacore but it’s clear that it began sometime in the early 1990s. One writer said it was the Cro-mags. The friend who I was cooking dinner with — a semi-grown-up crusty punk, for the record — says it was Shelter. According to Jerlyn, the Krishna thing started in Detroit with the band 108.

Like so much of American punk history, Krishnacore can be traced back to the Lower East Side, the same neighborhood that Prabhupada had made his first home in the United States some twenty years earlier. Since then, the Hare Krishnas had been through many ups and downs yet still maintained a presence in the neighborhood, particularly in Tompkins Square Park, where the Hare Krishna tree stands. As at ISKCON centers across the country, the Hare Krishnas would serve a free vegetarian lunch in the park every Sunday for the community, the curious, and the indigent.

The equation pretty much wrote itself: free vegan food + Lower East Side + public park = punks eating. The vegan buffet was prime time for Hare Krishnas to hand out their literature and talk to people about Krishna Consciousness. As it had for the hippies before them, propinquity proved fruitful for the punks.

The majority of Hare Krishnas in the United States, like most hardcore kids, were from white working- or middle-class backgrounds. Many of them had been involved in youth countercultures before becoming devotees. By the early 1990s, there were probably a couple devotees that had once been into punk too. The unique background of the organization, with its roots in the counterculture of the 1960s, made critiques of modern society their normative rhetorical mode when reaching out to new members. Considering this degree of commonality, once one looked past the robes and costumes, it’s easy to imagine how angry, world-weary, critically minded hardcore kids could feel comfortable hanging out with members of a foreign religious sect. It must have been eye-opening to see a new dimension to their revulsion towards consumer culture and the vapid hedonism of the world around them.

An extensive website maintained by a punk devotee in Australia, Mark ‘Vijaya‘ Langstone, provides a thorough history of Krishnacore pieced together from personal stories and fragmentary documentation of punk historians. (The most recent is a book by Brian Peterson called Burning Fight: the Nineties Hardcore Revolution in Ethics, Politics, Spirit, and Sound, published by Revelation Records.) The Cro-Mags, a hardcore band that formed in late 1980s, was the first to have members who were practicing Hare Krishnas, but the first band that made Krishna Consciousness front and center in lyrics and imagery was Shelter. (The Cro-Mags went on to corner the market on scowling horrorshow Vedanta thrash punk.) Shelter was founded in 1990 by Ray Cappo, formerly of Youth of Today, a seminal New York hardcore punk that was part of the first wave of hardcore in the late 1980s.

In 1991, the band 108 was formed. This was the band Jerlyn remembers being popular when she first got into hardcore. (I apparently wasn’t paying attention. I didn’t like bands that were “too screamy.”) Other bands followed. Worlds Collide. Refuse to Fall. Baby Gopal. Ray Cappo founded Equal Vision Records in the early 1990s to release Shelter albums. A few years later, Steve Reddy bought the label and began taking on other Krishnacore bands. The label is still around and has expanded to include all kinds of hardcore, emo, and metal-influenced punk. It also created a sub-label, Mantraology, in 2009 exclusively for “Krishna-conscious music.”

Kirshnacore combined the musical onslaught of hardcore — propulsive drums, repetitive guitar, monotonal scream-singing — with lyrics about freeing one’s mind from the illusion of material reality:

Don’t give me your costume.

Externals will suffocate me.

Don’t give me your costume.

I’ll try to reach inside.

I got to clarify, I got to amplify

All the reasons why I choose to serve and defy.——108, “Serve and Defy”

There are further divisions within Krishnacore — itself an esoteric subgenre of a subgenre of a subculture — aligning more or less with internal factions in the straightedge scene. Earth Crisis fused Krishnacore ideas with radical environmentalism. Propaghandi did the same with politics, raging against the injustices of capitalism and government oppression.

Probably the most extreme were straightedge “hardliners” who extended their ideology of nonviolence to diatribes against abortion. With names like Vegan Reich and Raid, they walked a thin line between fascist militarism and reactionary spiritualism. Considering the political atmosphere in the hardcore scene, the vocal stance on abortion was brave if not a little bizarre. Anti-abortion Krishnacore brings punk full circle: here were punk kids embracing a strict moral program of rules and boundaries and seeking to impose that program on others. It was the other side of room compared to the outrageous, irreverent antics of early punk.

Devotees who stayed involved in the hardcore scene would use the setting to “spread the good news,” i.e., evangelize. The presence of proselytizing hardcore kids at shows and festivals did not go over well. Peterson quotes several accounts of taunts, derision, threats and even violence — not just by people making fun of the faith but by newly religious Krishna devotees defending their worldview. Eventually, the anarchistic, grassroots culture of hardcore stretched to incorporate the lifestyle of these Krishna devotees. Their functional similarity to straightedge vegans softened the aversion people felt towards the dogmatic trappings of their lifestyle. By the early 1990s, literature on Krishna Consciousness and Hindu philosophy and visible signs of Krishna devotion were commonplace in the hardcore scene.

From our vantage point today, it might seen as though the Krishnacore moment has passed, or at least lost steam. Vijaya disagrees. It may have become less popular in the States but Krishnacore bands are cropping up around the world, he told me: Go X Mind! in Moscow, Bhimal in Poland, Sudarshana in Argentina, and FriendshipxSeva in the Philippines (described on their website as “the two piece ultrafast SxE Krsna crustcore outfit”) to name a few.

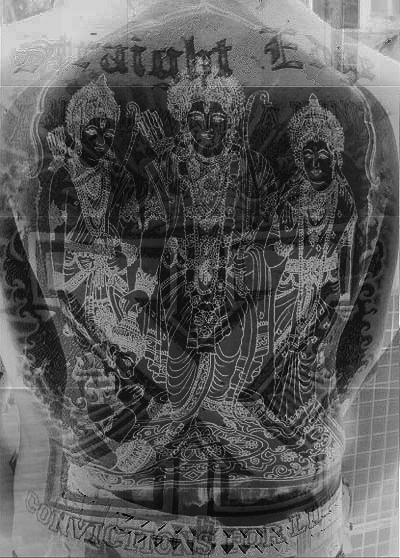

Seeing how passionate and widespread was the initial interest in the 1990s, the most curious aspect of Krishnacore is why it never caught on even more. Many took on the style and ambience of the Hare Krishnas and incorporated the ideas into their personal philosophy, even getting Krishna-themed tattoos and practicing Krishna devotion on their own. A few joined the Hare Krishnas but for the most part, Krishnacore never really went anywhere. It was and remains an obscure cul-de-sac in punk geography. It is referred to over and over again by people who were in the scene as simply a fad.

Hardcore in the Age of Kali

The whole idea of Krishnacore runs counter to the common conception of punk as an atheistic and cynical subculture that functions on principles of individual autonomy and anarchism. From the typical punk point of view, religion is just another power trap, an institution telling you how to believe and act. On top of that, punk is loud, raucous, and angry. By comparison, Hare Krishnas are soft and nonjudgmental or from the punk point of view, flaky and weak, occupying the same ideological territory as hippies, the subcultural nemeses of punks.

I had many questions about Krishnacore. How did the two subcultures come together the way the did? Was Krishnacore simply a “fad”? (Steadfast fans like Vijaya would disagree.) And what might this convergence tell us about the potential interweaving of antiauthoritarianism and spirituality?

But to begin with, how did Krishnacore make sense on a practical level?

I emailed Jerlyn. Besides the free lunch and cute boys, I couldn’t remember any details of our outing to the Fisher Mansion. Jerlyn told me that most of the kids in the vegan straightedge scene were into Krishna at least a bit. A few even “converted.” She listed off some names. One rung a bell. I’d had an awful teenage crush on Kamil. He had turquoise eyes and black hair. Whenever I saw him, he was sitting by himself at the local coffee shop sketching in a spiral-bound notebook. (This was before laptops.) Now I remember that Kamil wore a necklace of small wooden beads wrapped around his neck like a chocker. They were the Tulsi beads of the Krishna “devotee,” as Hare Krishnas refer to themselves. When I thought about it, I remembered a bunch of kids sporting the bead necklaces. I always thought it was just a style.

Jerlyn also mentioned Kevin, whom I vaguely remembered as well. Through another mutual friend (and the magic called the internet), I got in touch with him. Kevin was a hardcore kid who became a Hare Krishna and then a monk. He lived at the temple in Detroit for three years in the late nineties. He told me he got into Krishna Consciousness through Shelter and 108 (“of course”).

“At first I was totally unaware of the culture or philosophy. But I had a curiosity about it that lead to my reading some books and then visiting the temple. I just really developed a taste for it,” he wrote. “It seemed fun at the time. . . I identified being a Krishna devotee as a form of ‘ultimate rebellion.’ Not just against my parents or the government or against the lame mainstream or whatever — but against the whole material world itself.”

Later on, he explained that, “back then, to ignore Krishna Consciousness only meant bringing more suffering onto one’s self. To be a devotee of Krishna represented freedom and spiritual liberation.”

Kevin’s experience is a lens on how the fusion of punk and Krishna Consciousness took place, as a novel mixture of ideas, practice, and identity.

While it might be silly to imagine that punk scenesters have anything resembling a unified “philosophy,” they definitely embody a certain ethos and cultural position. Punk defines itself defiantly vis-a-vis dominant forms. It is heavily influenced by radical (especially anarchist) thought and celebrates individualism, anti-consumerism and self-sufficiency. Conversely, it rejects mainstream, bourgeois values. Straightedge is the puritanical wayward son of this original subculture, adding to the same stance a fundamentalist dedication to integrity and purity.

Now juxtapose this punk ethos against the philosophy of Krishna Consciousness as espoused by the Hare Krishnas. This philosophy is a branch of Vedanta, which is monistic and otherworldly in the sense that it views this world as inferior — less real — than another world beyond. For Krishna devotees, the material realm is corrupt and ultimately illusory; they aim to transcend it through ecstatic worship and meditation. As immaterial beings enmeshed in this material matrix, attainment of Krishna Consciousness is a way to lift ourselves up and out of the mortal coil, or so the idea goes.

The philosophy of Hare Krishnas, though hopeful in many ways, is also grounded in a fatalistic understanding of human civilization. According to the Hindu calendar, our current era is the Kali Yuga, the reign of Kali. During the Kali Yuga, greed and brutality rule; death and destruction are rampant. This reign began several thousands years ago, around the time that’s correlated with the dawn of civilization. It is scheduled to continue for another few thousand years.

These ideas, coupled with a stark criticism of the modern world, are something any punk kid can get behind. It appears that the Hare Krishna philosophy tapped into a reservoir of disillusionment in hardcore kids. It acknowledged the deep fucked-up-ness of the world while presenting a path of transformation and transcendence that was not too far removed from the path of being straightedge. A person pulled himself up from the inane, base desires of the world around him. The religion provided a philosophical depth to the vague constellation of style and pathos that framed hardcore straightedge identity.

Culture is not just ideas, though. It’s also art, iconography and patterns of behavior, what the anthropologist refer to as “practice.” When one looks closer at Krishnacore, it appears that the genre also flourished thanks to a random coincidence of cultural practices. As Kevin said, it seemed fun. But why?

The most obvious overlap was with straightedge. A lot hardcore kids had already sworn off animal products, intoxicants, wearing leather and even casual sex, which made being a Hare Krishna not that big of a leap, practically speaking. Straightedge kids and Hare Krishnas both kept unconventional diets that were interwoven with their critical views on mainstream society. And both broadcast their outsider status with a particular “costume.” In fact, punk and Hinduism both use conspicuous material signifiers to communicate allegiance and devotion. This was true even for straightedge hardcore, the most sparse and Calvinist of punk cultures. (The hardcore style — plain t-shirts, nondescript work pants, plain canvas shoes, Salvation Army sweaters, small earring hoops, black frame glasses — went mainstream a couple years later.)

Styles and symbols draw their power from the ambiguity of their meanings. Punk kids play with this quality, constructing a cut-up aesthetic from diverse images. Part of being hardcore was the printed t-shirts, stickers, and silk screened patches, the cover art, posters, and tattoos. For punk kids, Hinduism comes with a hoard of awesome graphics — icons, deities, and symbols — perfect for these purposes. It might not have been a conscious attraction but I suspect this is part of what made Hare Krishnas seem cool.

Then there were the sandalwood bracelets and necklaces (the Tulsi beads I remember on Kamil) that resonated with the sensitive-yet-tough image of hardcore. (At the time, in the early 1990s, the genre known as “emo” was just beginning to catch on.) Hare Krishna men shave their heads, as did hardcore guys. This kind of aesthetic overlap, purely coincidental, was enough to encourage cultural experimentation.

Then there were the social aspects. “We used to say Hardcore was ‘more than music,’ but I’d argue that it’s not about the music at all. It’s a community and a family. The music is a ritual,” said Norman Brannon, who played guitar in Shelter. Indeed, if you look at their investment in communal rituals, hardcore kids and Hare Krishnas have a lot in common. Hardcore kids go to shows where they dance (or what passes for dancing) and sing (or what passes for singing). Krishnas meet at the Temple or in public places for kirtan, the traditional singing and dancing that can go on for hours. The communal singing and dancing, and the trancelike state they produce, are primary shared practices. In both cases, an emulated speaker — guru or band leader — articulates words of truth. Underneath it all is the same uninhibited joy at sound, movement and raw expression.

However, probably the most basic element that connects hardcore punk and Krishna devotion is the break with accepted social norms. To be a punk, however subtle or overt, meant embracing one’s identity as a freak and social outcast, a cultural dissident of sorts. Once a person has been desensitized to the pressure of conformity, it’s easier to explore weird ideologies far and wide.

Hare Krishnas, well-versed in countercultural critiques, were able to tap into these commonalities. But there is still the obvious tension between the anti-authorianism of punk and the hierarchical nature of religious institutions (e.g., ISKCON). Krishnacore seems to defuse this tension. How?

As Kevin put it, “to ignore Krishna Consciousness only meant bringing more suffering onto one’s self. To be a devotee of Krishna represented freedom and spiritual liberation.” Krishnacore translates rebellion from the realm of the material (“political”) world into a higher realm of metaphysics. The rebellious attitude of punk is rooted in the conviction that the world is infuriating and off-kilter. That attitude is usually coupled with a call to action, whether it be withdrawal from society or confrontations with authority. It’s that call to action that gives punk its tendency toward radical politics. The same sentiment is expressed in a preoccupation with power, freedom and control. This is why punk is eternally attractive to teenagers: as a counterculture, it epitomizes the urge to commandeer control of one’s own life from the hand of arbitrary authority figures. It’s about rage, subversion, and radical empowerment.

Straightedge expands these ideas into the internal realm, creating ethical principles of behavior that re-appropriate control over one’s body and mind, and by extension, over one’s societal impact as a producer and consumer. As straightedge was an expansion and revision of hardcore, Krishnacore can be seen as an expansion and refinement of straightedge. The social critique — of consumerism, materialism, machismo — evolves into a deep disillusionment with the material world in general. Krishna devotion emerges as a profound program for ameliorating the suffering and shortcomings of the world by transcending it. The same principles and preoccupations — freedom, control, power — are central but they’re re-encoded in new vocabulary and practices.

For those punks who fully embraced it, Krishna Consciousness was a continuation of straightedge hardcore. It integrates a deep and comprehensive indictment of modern society with a firm belief in the will of the individual to change the world — not on a material level but on a metaphysical and personal level. Anyway, what could be more deviant — more “hardcore” — than joining the Hare Krishnas?

The Future of Devotion

The resultant fusion of these disparate streams of thought and practice is a fascinating case, however fleeting, of religious syncreticism. I set out to understand how this fusion worked on a subjective level, an ideological level, and a practical level. I was hoping to find grown-up hardcore kids who were still practicing devotees; I did, but only a few. But I also uncovered many more grown-up hardcore kids who are now ex-devotees.

Judging from experiences articulated by these ex-devotees, it appears that the tension between the anti-institutionalism of punk and the demands of Krishna worship was never fully resolved. From what I can tell, each of these individuals has been fundamentally shaped by the religious subculture. In the end though, they weren’t interested in being formal members of ISKCON or the Krishna community.

As Kevin put it, he just wasn’t “into it” anymore. “Basically I got bored with it after a few years. I lived in the temple as a full-time monk for two solid years. I just started to miss having a car, having a job, going out, playing music… GIRLS. So I just kinda started to lose my enthusiasm and then I moved out of the temple, got a job… I also started drinking beer (a big no-no for Krishnas) and breaking the rules, because I just wasn’t into it anymore.”

Robert Fish, the lead singer of 108, had a different take. “By the time I ‘left’ it was clear that I was more comfortable representing and speaking for myself and even my loose association with a religious sect did me no good. Also my philosophical inclinations were different than what one has access to in ISKCON so that was that. … I was always a bit on the outside.”

Norman Brannon is now a DJ in New York. In an interview for Scanner Zine from 2008, he said he had stopped practicing as a Krishna devotee about three years prior. “I was looking for something intangible and I found it there. I ultimately left because my passion for the whole thing just wasn’t really there anymore. I didn’t want to just go through the motions simply because I had been involved with this thing for fifteen years — you know what I mean? It was part of a larger reevaluation process that was really important for me. “At this point, I’m more of an agnostic — in the generic sense of the word, anyway — but I appreciate and respect the Vaisnava philosophy and lifestyle greatly. I mean, I would still count the guru that initiated me into the movement as one of the most important people in my life.”

Then there are those who stayed within the institutional framework of ISKCON. Most seem focused on bringing more people into the group. Vijaya was open in talking about the obstacles of being a part of any institution but he sees that as inevitable, a fact of life he’s made peace with. As for hardcore, he told me he was “more involved within the Krishna movement [than the hardcore scene] but I write articles for zines and websites and stay in touch with many scenesters for the purpose of spreading the [Krishna] culture there.”

Vic De Cara, a former member of the band 108, is still a practicing devotee. In an interview in the zine War on Illusion, he is frank about his approach to hardcore. He says of 108, “I had been doing 108 not because I was so much attracted to it but because I felt it was the right thing to do. It was my service to Krishna, and I did it.” When he quit 108, he started a school within ISKCON to educate incoming hardcore kids. About 108, he says, “our biggest accomplishment was that we reached certain people who were otherwise unreachable.”

Ray Cappo (a.k.a. Raghunath), whose website my friend and I stumbled across while making dinner that night, seems to be an exception. He was one of the first faces of Krishnacore. Today he is a yoga instructor and, from what I can tell, still a devotee although it’s not front and center in his public persona. It’s not even clear if he’s formally associated with ISKCON.

For every person that stayed with the practice, there are a few others who drifted away. These people are harder to find since they’re obviously not as eager to talk to strangers about Krishna Consciousness as those who are looking to spread the faith. Those who left ISKCON but still practice Krishna devotion are not organized in a communal sense. Their spirituality is mostly a personal matter.

Its unclear if Krishnacore in the United States will survive beyond the few individuals who are still devoted to this unique cultural amalgamation. The subculture remained largely ornamental, an aesthetic subgenre of hardcore punk, and was never a substantial synthesis of the two lifestyles in a collective sense. From what I can tell, devotees who came to Krishna Consciousness by way of straightedge hardcore were no different in practice or belief than any other devotees — except perhaps that they deserted more frequently. In short, the antiauthoritarian stance of punk never took on the institutional hierarchy of ISKCON. A full-scale Krishna sect with a dispersed, consensus-driven and transparent power structure (or radical political leanings) never developed.

Prospects for Countercultural Spirituality

In the last half-century, religion has been undergoing a massive shift. Church attendance in the Western world has been steadily declining. At the same time, so-called alternative spiritualities are growing. Yoga studios, New Age centers, and mediation practice are on the rise among the otherwise unaffiliated. A theme running through all of these transformations is the negotiation of modern individualism, authority, commitment (communal and personal), and the hunger for wisdom and transcendence.

The unlikely fusion of straightedge hardcore and Krishna devotion is one example of a creative attempt to deal with these issues. What does it tell us about how the ethos of punk might be elaborated within the framework of spirituality? Because punk is one of the most significant countercultures of the last forty years, this is a question I ponder in my intellectual wanderings at the intersection of counterculture and alternative spiritual movements. Most fusions of counterculture and spirituality, like the early Hare Krishna movement in the United States, took place among “hippie” subcultures that abandoned political analyses for a “higher” perspective, leaving them open to authoritarian or exploitative power structures. Would the fusion of punk and spirituality be different?

While it’s easy to see punk as a juvenile halfway house before one moves on to adulthood, this would be ignoring the importance these youthful subcultures hold in their ability to sow critical perspectives and identity. Out of these subcultures grow social movements with the power to shape society. The tacit connection between punk and radical politics is a case in point. With the decline of organized religion and the rise in “spirituality,” more creative fusions like this one are likely. In this context, the example of Krishnacore is murky at best. It seems that the radical principles of punk got lost in the shuffle and the hardcore devotees were either subsumed by ISKCON or left to practice on their own.

It’s possible that the punk ethos is simply too precarious by nature; perhaps it’s inherently antithetical to communal stability. To take this a step further, it’s possible that radical politics, based on a materialist critique of power structures and the allocation of resources, is by nature materialist; perhaps this materiality is fundamentally at odds with the metaphysical focus of the Vedantic worldview. With the phenomenal spread of yoga practice and the attendant seep of Vedantic philosophy across the Western world, it’s only a matter of time before Krishna devotees break away from ISKCON and form their own distinct social organization and cultural bend. Time will tell what these communities might look like.

Still I wonder, what would a punk-influenced spirituality look like? What might be the defining characteristics of a radical spiritual community?

Like much religious devotion, punk is about renunciation and reclamation. As the 108 song goes, its about choosing to serve and defy: to defy false gods and serve chosen ones. After Krishnacore, more hardcore bands emerged that screamed and thrashed out spiritual messages, from Islam, Judaism, and even Christianity, to crowds of sweaty, stage-diving teenagers, attesting to the fact that the subculture was eager for a spiritual dimension to their ethical theorizing. Krishnacore does leave us with one valuable lesson, taken to heart by the punk anti-institution, Food Not Bombs. The key to starting a revolution, spiritual or otherwise, might be free lunch.

Great exploration of one of the weirder edges of punk. I would question however the assertion that “hardcore became nearly synonymous with straightedge.” From what I understand straightedge (sXe) itself was a significant but small element of the broader hardcore scene.

Interesting article on a very interesting subject… I delved into this a little (though much more superficially) on one of my blogs in 2008:

http://roughinhere.wordpress.com/2008/05/03/poly-styrene-x-ray-spex-and-the-hare-krishnas/

That was when I was still devoting that blog to a wide range of “global music” (and culture)… In the time since then, that blog has transformed into one devoted exclusively to very old Indian film music because, well, I like that music much more. 🙂 (Though the blog I’m linking this post to keeps up the “global” tradition a bit…) And, by the way, I have always wondered if joining the Hare Krishnas gives you a chance to hear lots of Indian music (since I know you get to eat lots of Indian food). If this is the case, why would any punk rocker who joins the Krishnas continue to be a punk rocker and not become a complete Indian music fan? Actually, I’m just kidding there… I wholly respect people’s decision to join the Krishnas but remain “hardcore.” (And anyway, if I decided to join a spiritual/religious group strictly for love of the music, it would more likely be the Sufis.)

As I mentioned in my post, I can’t think of punk rock Krishnas without thinking of (recently dearly departed) Poly Styrene, of X Ray Spex. Understanding that old school punk is not the same as hardcore, I still think that if we want to talk about punk rockers becoming Hare Krishnas, Poly would have to be considered the godmother of that trend. Certainly, she was the first punk rocker (of any kind) whom I heard about doing that sort of thing. And though I never heard her do music connected to the Hare Krishnas, when I heard about her conversion (possibly in the very early 80s), I wondered what punk rock and the Hare Krishnas might have in common that would explain the phenomenon of someone in that musical subculture joining that cult. Yes, I was asking the question even back then. 🙂

———————–

P.S. Felt like looking Poly up on Wikipedia and, wow, it says that the first X Ray Spex saxophonist, Laura Logic, joined the Krishnas at the same time as well…