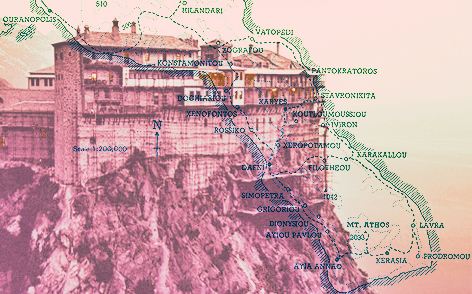

One of the more astonishing moments among autobiographies appears in Maryse Choisy’s Un Mois Chez les Hommes (1929). In preparation for a visit to Mount Athos, the long peninsula in northern Greece that constitutes a monastic republic where, by religious edict, women have been forbidden to visit for over a thousand years, Choisy relates how she decided to have an elective bilateral radical mastectomy. She called it the ‘Amazonian’ surgical procedure and undertook it with her boyfriend’s agreement. It worked: she was able to pose as a male servant, smuggle herself over the isthmus border beyond which women are prohibited, and spend a month wandering between the peninsula’s twenty monasteries.

Choisy, briefly a patient of Sigmund Freud, had a personality that swung between enthusiastic extremes. Her immediately previous book, Un Mois Chez les Filles (1928), had been a participatory journalism study of a Marseilles brothel. She went from sexual dissipation to self-mutilation and chastity in the space of two closely-spaced books. Much of the remainder of her career was taken up with an intellectual effort to synthesize psychoanalysis with Christianity, an issue of concern especially to conservative Catholics in Europe. That’s why Choisy’s work remains one of the curious corners of French psychoanalytic history.

Choisy’s choice to cut off her breasts was capitulation to religious misogyny promoted as spiritual purity. She surrendered visible parts of her physiological femininity as the price for a month’s worth of acceptance by men in a world that was all male world except her. Her travel account contains almost no reflection on her decision, seeming to accept her loss as a necessary ticket for admission. Aliki Diplarakou, a Greek beauty queen, followed Choisy by a few years in managing to infiltrate Athos dressed as a man, but did so with an intact chest.

Choisy’s story of travel on Athos is one of gender victimization, even if she fails to recognize the act of sacrificial subordination she performs. Like other transgressive narratives such as that of Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Choisy’s narrative has been dismissed as a made-up fraud. That is an unfounded allegation of the sort which is quite familiar in the reception histories of women’s and minority literature. Still, Un Mois Chez les Hommes is the only one of Choisy’s many books that has been translated, once into English in 1962 and again into Greek in 1980.

Vastly preferable to Choisy’s approach in my eyes was the style of an armed communist all-women platoon during the Greek Civil War that invaded Athos in 1948, occupied its capital village of Karyes for a few hours, exchanged fire with the police, and confiscated all the monks’ mules for their retreat. This was perhaps the boldest violation of the avaton (prohibition on women), its originating 9th-century rationale being a dedication of the peninsula to the Virgin Mary, so that any woman trespassing offends against her. There were a few Victorian-era foreign women who succeeded in debarking from boats into ‘the womanless land,’ such as Lady Stratford de Redcliffe in 1852 under the aegis of her diplomat husband and Lady Fanny Janet Sandison Blunt in 1897. Gender-inspector monks have long been stationed at the tiny port of Daphni to prevent such attempts.

A more recent landside incursion occurred in January 2008 of a half-dozen women, including Litsa Amanatidou-Paschalidou, a Thessaloniki parliamentarian representing the Coalition of the Radical Left. They broke away from a demonstration of several hundred villagers against property claims by Athos monks and entered Athos territory briefly in order to bring attention to the problem. Women are currently limited to approaching no more than 500 meters from the Athos coast, as did Russian first lady Svetlana Medvedeva in 2009 when she met a boatload of monks who came to receive her at sea. Women with an interest in Athos are forced to take tour boats that remain outside the 500-meter limit. That is a stricter regime than in the 18th century, when the wives of fishermen were allowed to land on the coast but not step out of their boats. They may not have wished to in any case, since popular belief in the Aegean held that any woman so presumptuous as to set foot on Athos would be struck dead by the divine powers. This prohibition against females even extends to the animal kingdom: with the exception of hens for eggs and cats as mousers, female animals are prohibited. The moral laxity represented by excess feminine fowl, however, led to the Great Hen Massacre of 1932. Religious folk legend holds that even female wild birds that violate the ban fall dead from the sky.

For humans at least, the European Union has taken exception to this gender segregation that has been protected under Greek law since 1926 and whose violation carries criminal penalties. In 1997 the European Court of Human Rights refused a petition from members of the European parliament to rule against the ban. Four years later in the context of a review of human rights in Europe, the EU Parliament in 2001 resolved that the avaton “violates the universally recognised principle of gender equality, Community non-discrimination and equality legislation and the provisions relating to free movement of persons within the EU.” (Resolution 2001/2014(INI), clause 98) Not surprisingly, this suggestion that the Athos community end over a thousand years of adherence to its medieval code met vehement rejection from both the monks and the Greek government.

Anna Karamanou, a former EU parliament member representing PASOK, the Greek socialist party, has condemned the situation for years. In 2001 she said “The ban was imposed 1,000 years ago, when Europe was in the dark grip of the Middle Ages, and reflects the social reality of those times. Nowadays, it can have no effect, as it conflicts not only with the modern understanding of human rights but also with the Christian faith itself… No tradition and no custom can be above the respect of human rights and dignity.” Karamanou has continued to argue that Greek and EU women taxpayers support architectural restoration of the monasteries yet remain denied access to the cultural heritage Athos represents. She is one of the few in Greek politics who identifies the symbolic importance of the gender ban at Mount Athos. Even if sympathetic, others treat the issue as a marginal one, less important than achieving women’s economic and social equality.

Karamanou and Greek feminists demanding that the avaton be ended and Athos opened to women are on the progressive side of history, the side that demands expansion of human rights. The persistence of the avaton encapsulates a conflict between an old patriarchal order and an emergent new equalitarian order. In the old order women are a source of impurity and their appearance constitutes an irresistible sexual temptation, while at the same time religio-cultural rhetoric praises women as righteous, honorable and praiseworthy so long as they know their inferior place. The old order seeks to cleanse public spaces of women and divide private spaces into male and female domains; the new order, generations in the making, seeks to guarantee equal participation and social power for women. Athos is far from alone among world religious sites in its old-order taboo. In Japan, for example, the area of Mount Omine and its Ominesan-ji temple site have remained forbidden to women for a similarly long historical period and now attract genders equality protests.

In his 2004 memoir We Jews and Blacks, the poet Willis Barnstone recalls a visit to the Holy Mountain, writing “In Athos the prejudice against women simply intensifies, in this holiest of places…the essential sorrow of Christianity, and virtually all religions, which see women as property, as child-makers, as servants to their husbands.” Exclusion constitutes intensification of devaluation, marginalization, and ultimately prefaces destruction of the unwanted. The avaton – which begins with that low fence across the Athos isthmus – is an ancient theological iteration of boundary-marking that finds its historical kin in the ghetto vecchio of Venice, Jim Crow railroad cars, dalit villages in India, and the gender apartheid of contemporary Saudi Arabia. Each of these exclusions represents an offense to human dignity, one whose historicity does not constitute justification for continuance.

Yet it is that same exclusion that generates international appeal. In the travel literature of Athos there are men who admire monks as representatives of spiritual attainment possible without the distraction of women. Monks represent a pre-Eve Adam, one who contemplates the world alone. There are repeated stories of adult or elderly monks who were brought to Athos at a very young age and who have forgotten what women look like. In Mount Athos, Thessaly, and Epirus: Diary of a Journey from Constantinople to Corfu (1852), George Ferguson Bowen describes an encounter with a 28 year-old monk who was brought to Athos at age four and had forgotten even what his mother looked like. “He was very inquisitive about women, whom he had heard and read of, but had never seen; of whom, in short, he appeared to know about as much as I know of crocodiles and hippopotamuses.” Instead of considering the tragedy of being cut off involuntarily from half of humanity for so many years, Bowen reassures the young monk that this is no loss, that his soul was guaranteed for heaven and that he should “thank Providence that he, at least, was safe from the allurements of those syrens of real life.” A British visitor with an official party touring the Athos coast by steam-boat during the early 1870s had considerably more charity when confronted by a monk with a similar biography. “One poor fellow asked me, in broken Italian, if women were anything like pictures of the Virgin…I told him to come on board when we went off, that he might see their faces once before he died.” The pitiable monk came aboard ship along with several others joining him for the same purpose.

One National Geographic writer in 1916 crowed about this ban: “For I must reveal to you, O feminists, suffragists, suffragettes, and ladies militant of the western world, that here is a stronghold secure against your attacks.” For him and his sort to the present day, Athos represented a spirited defense against modernity and gender equality. More contemporary defenses tend to emphasize a claimed right of Athos monks to preserve a cultural uniqueness manifested through life without sight of women. In his recent travelogue and history of Athos, Mount Athos: Renewal in Paradise (2004), Graham Speake acquits the monks in milder terms: “They are not all misogynists, but they regard women as a distraction from their vocation.”

If Athos were an all-white establishment and we were to recast the same statement in racial terms, that same line might read ‘They are not all racists, but they see blacks as an unwanted distraction and exclude them.’ With that rephrasing the unacceptability of such a defense becomes apparent. Another species of apology points to the development of nearby Orthodox women’s convents as a substitute for entering the Athos peninsula. Kyriacos Markides writes “It is as if, to accommodate women, a parallel Mount Athos is gradually being created.” But separate-but-equal accommodation arguments remain as unacceptable for gender as for race.

One of the more interesting ruminations on the gender challenges of Mount Athos comes from British journalist Victoria Clark in Why Angels Fall: A Journey through Orthodox Europe from Byzantium to Kosovo (2000). As an EU citizen she is deeply angered to be “imprisoned on a boat” viewing the Athos peninsula only from afar on the sea and perturbed that the Orthodox women who are her fellow passengers apparently do not share her distress. She considers crossing the land-wall, getting arrested, and making a legal case of the matter before the European Court of Human Rights. Such a case might highlight, she speculates, not only citizenship rights but the cultural divide between the Orthodox culture of eastern Europe and the Catholic-Protestant culture of western Europe. In the end, however, she decides that a clandestine nighttime entry or putting on a false beard will do very little in pursuit of cultural knowledge. Clark quite intelligently questions the epistemological value of forceful invasion, especially as she shares so little of the religious culture Athos embodies. The counter-question, though, is whether there is a valid balancing test between epistemological suspicion and civil rights?

For their part, ecclesiastical authorities on Athos regard the entire discussion of admitting women visitors as an impossibility that would end monastic civilization on the peninsula. Their purpose lies in continued distancing from the cosmopolitan world of which women are part. Athos is the world over which they rule, as guaranteed by the Greek constitution and a derogation clause in Greece’s accession treaty to the European Union that limits right of free travel on Athos. In this view, demands to open Athos to women constitute infringement on its right to self-governance. Such demands voiced within the EU, as they have been since at least the 1990s, are regarded by the monks and their lay advocates as just another source of assault on the spiritual integrity of Athos. Religious authorities on Athos have counter-demanded that the EU recognize its special status and protect its traditions.

Yet Athos is both a juridical territory of the European Union and one of the cultural treasure-houses of the world, containing monastic libraries of immense value. Self-government that discriminates against half of humanity, refusing access to either the territory or its monasteries, is government that abuses such autonomy. Similar claims of ‘private property’ were the unacceptable rationale of Georgia segregationist Lester Maddox when he chased blacks out of his Pickrick restaurant in the face of the 1964 Civil Rights Act guaranteeing equal access to public accommodations. Denial of access constitutes a positive harm, harms that range from the mild in Edith Wharton’s unhappy reflections in her 1888 travel diary that became The Cruise of the Vanadis to the dramatically severe in Maryse Choisy’s self-mutilation in order to gain entrance. Equal access is equal citizenship, and equal citizenship is not profanation.

Years ago, after several hours’ hike from the Megisti Lavra monastery together with my brother and a German judge as our walking companion, I stood on the trail and admired the soaring walls and layered balconies of the Simonopetra monastery. It rose above a sea that ranged outward from pale to deep blue. Small terraced gardens lay at the foot of its heavy walls built into the living rock. The beauty of the scene was undeniable, but one was also struck at the centuries of brute labor by monks in order to create that visual magnificence. The materiality of labor and community was far more meaningful than Orthodox spiritual claims. Simonopetra’s architectural aesthetic could be appreciated in the same sense that we admire Shaker furniture or the Chartres cathedral windows while rejecting Shaker or Catholic theologies.

Despite the millennial exclusion of women from Athos because of misogynistic religious beliefs, the labor of unnumbered women was an indelible component of the spectacle. Their labor produced every single monk and male worker who created Simonopetra and all other Athos monasteries. Women have a right to visit and see the fruits of their labor. The long-overdue end of the Athos avaton will commence recognition of their rights.

What an incredible story! Thanks for bringing this unimaginable history to the 21st century.

You have some fair points, but it all comes down to this. It is not about gender equality and Athos is not a public place. The whole peninsula is the private property of the monasteries for centuries now, thus they have the right to decide who they let in. Exactly the same way you decide who you let into your house. The monasteries are the homes of the monks and the surrounding land is their garden. No women ever lived there for centuries, so no women suffered in any way because of the actions of the monks. The monks have chosen a way of life in which they believe that they must seclude themselves from anything that brings pleasure, and that includes female contact. Since Athos is their property, their home, they have every right to enforce it. And even if women were ever allowed in Athos, it is unlikely that they would ever been allowed in the monasteries which by definition are not public places. And in any case, women of faith seem to understand the point of view of the monks, as it is mainly the left-wing atheist type who seem to object to the avaton. So I can hardly imagine that a working male monastery is a place of interest for this type of women. As a last point, Athos is the incredible place it is today, partly because of restrictions like the avaton. Allowing women and mass access of tourism would simple destroy this peninsula, make the monastic way of life dissapear, and turn the whole place into another tasteless greek summer resort. I don’t think that allowing a few thousand men to deny the pleasures of the flesh in their isolated plot of land, is any threat to women’s rights worlwide…

@ George: The Athos peninsula is ‘private’ by virtue of the protections of civil law, specifically article 105 of the Greek constitution guaranteeing its sovereignty and the 1926 law criminalizing women’s entry. Most contemporary human rights law theorists would agree that civil law should not engage in protecting gender discrimination based on private-property claims against public access. Nor do private-property claims constitute sufficient basis to underwrite discrimination in a public accommodation, as the article points out. Athos, with a population of roughly 2,000 monks, grants entry to 100 visitors per day — making roughly 36,000 visitors annually. A non-discriminatory entry system would ensure that half of these entries are granted to women. Many women of faith, I am sure, would be very interested in visiting this UNESCO World Heritage site. If an even older Orthodox monastery such as St. Catharine’s at Mount Sinai can manage to pursue its monastic mission while hosting women visitors, then Megisti Lavra can accomplish the same. The part of your argument to which I am quite sympathetic would be opposition to mass tourism. That would defeat the legitimate purposes of Athos. However, there is no necessary correlation between mass tourism and opening access to Athos on a non-discriminatory basis.

A bunch of people own a peninsula and don’t want to deal with women for a variety of reasons, part of which is they don’t want to have any temptation in their lives. Go champion the cause to end female-only gyms or swim sessions in Europe (http://www.thecamp.co.uk/ http://www.conworld.net/index.php/Venues/bella-sky-hotel-first-in-europe-with-women-only-floor.html http://www.holidaystoeurope.com.au/home/index.php?option=com_content&task=blogcategory&id=78&Itemid=184 http://www.gomio.com/en/hostels/europe/italy/rome/Orsa%20Maggiore%20for%20Women%20Only/overview.htm) if you feel so strongly about these things rather then forcing your way on people who are doing you no harm and who have certain practices which they hold to as a part of their monastic order. Their culture and society isn’t yours to end.

@B. Kelly: The same rationalization might be employed to justify gender apartheid on the Arabian peninsula rather than the Athonian peninsula. Athos does not have exemptions from EU law on gender discrimination.

So what I get from you is that it is OK for there to be women only places as I showed, but not men only places? But you’re going to point at the law in this case even though the law isn’t on your side either since the treaty by which Greece entered into the EU allowed specifically for Mt. Athos to operate as it has been which the EU is lawbound to uphold.

If you own land do you or do you not have the right to choose who is allowed to enter or not? Can I do some grilling in your backyard? May I park a caravan in your garden plot? Or do you have more control over that than you want those monks to have? How about if someone forces you to worship God, how about if you must do it on their terms? Those monasteries are part of how they worship God.

@ B. Kelly: Imputing a response that was not given puts words into others’ mouths and misdirects attention. It is better to focus on the case at point. As for the interpretation of EU law offered in your comment, the EU parliament disagrees emphatically (see above). Regarding the remainder, claims of private property protection for public discrimination are antiques from another age. This was the argument that Lester Maddox used to run blacks out of his restaurant with a baseball bat — it’s my property so I can keep out any sort of people I want and let in others. That rationale does not make discrimination acceptable, nor do claims of religious privilege.

I have not put words in your mouth. I have dealt with the consequences of your argument. It continues to be the consequence of your argument. Sex discrimination is OK for you in some cases and not in others. This is even more true in light of your Maddox argument that you try to liken this to.

Their property is not like a restaurant in terms of private property. They aren’t selling services to people. It is where they live. You can allow people into your house if you choose. You may not tell others that they have to allow others into their house.

This is how they worship God. For you to insist that others dictate what they do with their property in this manner is the same as you telling them they have no right to worship God as they are and that their culture must die to suit yours.

The EU parliament agreed to the conditions of Mount Athos when Greece was allowed in. That a handful of people want them to change it has no force of law. This is a part of their culture, it is their land, and the law protects them. There isn’t any part of your argument that is accurate or compelling.

The EU parliament repeatedly has adopted human rights reports calling for an end to gender discrimination in access to Athos and criminal penalties for women entering the territory, pointing out that this contravenes EU guarantees of free movement and international conventions against gender discrimination. This is the EU parliament, not “a handful of people.” Beyond that, I don’t think this exchange is going anywhere.

Joe, it has been only a handful of people who have insisted on trying to contravene Greek law and the treaty which brought Greece into the EU. This would be plain if you actually looked into your claims. Athonites have a right to self-determination. Now if you’ll excuse me, I have a cook-out to organize in your backyard.

The basic research gateway for EU parliamentary documents is located at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/en/headlines/ See lower left under the drop-down menu titled ‘Access to documents.’ A search on ‘Athos’ will provide access to EU parliamentary reports on human rights that address this issue.

Which does nothing but corroborate what I wrote,

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=CRE&reference=20010705&secondRef=ANN-01&language=EN&detail=H-2001-0567&query=QUESTION

Never been to that site before however I have read the documents. It might do better if you can show your claims rather than expecting me to show you why you are wrong. You seem to disagree with a freedom of religion concept and you seem to not be able to accept that the law and such are specifically not on your side here.

The European Commission and the European parliament are different bodies — the difference between the EU’s executive and legislative functions is a basic point, one that your link suggests you fail to understand. The article above indeed cites an earlier EU Court of Human Rights opinion refusing to get involved with the ban, quite similar to the Commission’s position reported in this link. The article then cites movement against this position by the European parliament and its resolutions. Selective citation of evidence is a poor practice, so one should provide a balanced and relevant history. That EU parliamentary history — not included in the article — includes repeated approval of its committee reports citing the Athos ban on women as a violation of human rights and international law. Perhaps it would be useful to learn about and check the basic EU information sites before commenting.

I’ll remind you that you have yet to give any evidence at all. My “selective evidence” is taken from what you chose to tell me to look at (which was just slightly more narrowly defined then telling me to Google your claim).

Perhaps it would be best for you to actually factcheck your claims before you make them? I certainly checked out the relevant treaties before I referred to them.

Souciant is not a scholarly journal with footnotes. Nor am I required to present research at your bidding. The nature and tone of your comments are a good example of why I do not like talk-backs — free insults from those who know little, do no research, argue poorly, and cannot be bothered writing an essay on their own. If this topic moves you, perhaps you would do better to expend the effort and elbow-grease to write an essay with an opposing point of view. I have responded sufficiently here.