For the last month, my wife and I have lived next to a synagogue. Not just any synagogue. Perhaps one of the most beautiful ones in Europe. The Great Synagogue of Turin, on the Piazzetta Primo Levi. First constructed in 1884, the monumental structure befits its location. Styled in a deliberately Moorish fashion, with classically Islamic details, it betrays the close proximity of the Middle East.

The fact that the synagogue is smack in the middle of a largely Muslim immigrant neighborhood does little to depress such associations. One block away is a Moroccan restaurant. Several Berlin-style döner kebab parlors sit a block to the west. Three halal grocery stores lie two blocks to the north. Our downstairs neighbor wears a hijab. She likes to play Om Kolthoum on the weekends. Her wi-fi network is named, rather appropriately, donerbackup.

“Atah Israeli?” (Are you Israeli?) yelled a man with short hair and a khaki vest, standing at the building’s Piazzetta Levi entrance. “Ken” (‘yes’) I replied, as he looked me over, curious about my presence. Having overheard me say “Abba” to my dad, whom I had just started speaking with on my mobile, I’d given him entrée. I got back on my phone, and continued speaking with my father. He made no further attempts to interrupt.

This is the first time I’ve lived so close to a synagogue. Raised in a stereotypically secular Israeli household until I was sixteen, I had no idea what Tisha B’av was until I took a class on Judaism my junior year in college. My professor asked me something about its significance in the Jewish calendar. The only thing I can remember is being embarrassed. Intensely ethnic in my personal identity, I had no grasp of the religious tradition on which it was theoretically founded.

For the last few weeks, I’ve felt the same way about the synagogue. For as many times as my wife has asked me questions about Italian Jewry, the only thing I can do is talk about the Piazzetta’s namesake, the late author Primo Levi. “You know, he was opposed to the war in Lebanon,” I said regarding Levi’s controversial positions on the 1982 conflict. “Apparently his opinions were not very welcome in the community.”

I feel bad for not knowing more. According to family lore, my paternal great-great grandparents were Venetian. Like many Italian Jews, their ancestors fled to Italy during the Inquisition. Timber merchants, they remained in Venice until the early 19th century, when the family began moving to other parts of Europe, and, as in the case of my immediate ancestors, eventually Ottoman Palestine. The last Italian Schalit – a cantorial composer from Mantova – is supposed to have died during the Second World War.

The fact of the matter is that my curiosity stops there. Call me narcissistic, but I’m far too preoccupied with the details of what I see now to want to become an expert on Jewish life in ancient Rome, or whether Columbus, who lived nearby, in Savona, was in fact a Sephardic Jew. So, for example, I find it far more interesting to consider why, throughout central Torino, there are stickers posted to the backs of municipal signs and lamp posts calling Piazzetta Primo Levi ‘the most beautiful square in Torino.”

What does that mean? In this square, aside from the shul, the only thing worth visiting is an overpriced health food store. Suffering from dairy allergies, I of course go there for all of my soy products. Stocked with conspicuously German organic brands, such as Rapunzel, if it weren’t for all of the local artisanal pasta, you’d think you were in Berlin. Not to knock Rapunzel, or make jokes about Nazi vegetarians. The location is still funny.

What’s most eye-catching about Piazzetta Levi is the military presence. Twenty-four hours a day a camouflaged Italian armored vehicle sits in the square. Two soldiers usually sit inside, while another two stand outside, scanning passersby. Always Alpini (mountain commandos), you can tell what part of the Italian army they belong to by the style of hat they wear: pointy, olive green caps, with a large feather affixed to them.

Their camouflage outfits are distinct. An Italian take on American digital camos, there’s something particularly local about their stylishness. Having lived in Italy when I was a child, the visual affect was not unfamiliar. Witness to countless Italian security personnel on Genoa’s streets (it was the mid-’70s, during the Years of Lead) I remember how well-dressed the paramilitary Carabinieri were, with their tailored black outfits and perfectly fitting berets. They looked like more fashionable members of the SS.

The Alpini are less scary-looking. I don’t know whether it is the earthy colors of their uniforms, or the fact that they are protecting a synagogue that makes them appear less threatening to me. They stand next to a cement barrier with the words “Fuoco al Lager” (‘Burn the concentration camp’) scrawled on it, pistol at the ready, while young Jewish children walk by on their way to day school. I feel protected myself.

Well, somewhat. The graffiti is a dead give away. For those Jews who monitor racism in Europe, the security provided to the synagogue appears absolutely necessary. Danger could come from fascist anti-Semites. Or, more likely these days, Jihadis ramming the building with a car full of explosives. To activists who monitor European anti-immigrant politics – the kind associated with Centers for Identification and Expulsion (CIE, as is referred to in the second barrier in the photo) – such graffiti facing a synagogue is its own ironic reminder that Jews are still considered different, too.

This is not to say that Jews are considered immigrants. Especially in a place like Italy, which hosts one of the world’s oldest, continuously existing Jewish communities. Rather, because so much of the racism to which non-Jews, as well as Jews, remain subject is continually tinged with the imprint of German fascism. Though this may be common sense to some, as Nazism is understood to have incubated many hatreds, as a Jew, you are also taught that Muslims study and ape Nazi anti-Semitism too.

So, if you know this, and you see graffiti like “Fuoco al lager” next to a synagogue surrounded by kebab shops and halal groceries, it can be a source of dissonance. Especially when an explicitly Jewish institution remains so heavily guarded by soldiers. Is the graffiti there in order to remind us that we are more like our neighbors? That we must be more sympathetic, or that we must identify with them? Or is it simply a reminder that we exist as part of a community that continues to be considered different? That our neighbors are seen to be more like us than we are like Italians?

In most European cities today, it is not uncommon to encounter swastikas scrawled on buildings. In Italy, in urban settings, the Nazi symbol is oftentimes as common as its antitheses, the anarchist A and the communist sickle and hammer. Its familiarity, unfortunately, makes sense, as it coincides with a rise in rightwing, anti-immigration sentiment, and racist attitudes towards Europeans of Middle Eastern and Muslim descent.

Hence my lack of surprise, when, around the corner from the synagogue, I encountered the slogan “Juden raus” scrawled on the wall. A sticker for Italy’s Refounded Communist party had been pasted over “Juden.” However, someone had begun to peel it off. A swastika is partially covered by another Rifondazione sticker underneath. Needless to say, the discourse fit the prejudice. Jews were being incited against not from an Islamist perspective, but a fascist one. Not in Italian, but in German. Whoever wrote it, the continuity was still there.

Ten blocks away, on Via Belfiore, sits a döner kebab parlor. When I first arrived in town, I noticed it, because of a large mural that had been painted outside the door. Like the slogan on the anti-car bomb barrier in front of the synagogue, it referred to the CIE. “No Ai CIE” it read (No to the CIE). The accompanying graphic are helmeted security personnel carrying away a non-descript person. It is a particularly jarring image.

I recognized it, because my wife had taken a photo of it before I arrived. “The immigration politics will remind you a lot of Via Padova,” Jennifer said. “At least in terms of the local street art.” She was right. In some respects, this was even better than Milan. Because Torino is a city with a more liberal political reputation, of course there would be differences as well as overlap. Unhappy with the last picture I took of the mural, last week I decided to go back and take better pictures.

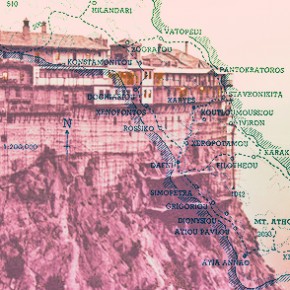

When I arrived, I found the original (see the lead photograph in this essay). It was the same, except that someone had since spray-painted a large swastika over it. As though by doing so, they were communicating the idea that the antithesis of a Europe with döner shops in it is one that is fascist. I couldn’t help but assume that these guys were saying the same thing as whoever had written “Juden raus” around the corner from the synagogue. That they wanted us all to go, because their ideal community was the same one that once excluded ours.