The other day, a friend of mine asked me to share what media I’d been taking in lately. Even though it was a logical request, I was reluctant to respond. Instead of keeping tabs on new releases, I’ve been spending my limited time and money indulging in familiar pleasures: Haruki Murakami’s A Wild Sheep Chase, Bruce Springsteen’s Born To Run, and just about everything to do with J.R.R. Tolkien.

The more I thought about it, though, the more clear it became that revisiting these long-time favorites of mine wasn’t simply a retreat into the past. I was rereading Murakami’s novel in preparation for a piece I’m writing about personal rituals, but also in anticipation of the October publication of my favorite writer’s magnum opus 1Q84 in English. Born To Run was in my CD player as a way of paying tribute to E Street Band saxophonist Clarence Clemons, who just passed away. And my mind was full of Middle Earth because my ex and I have been taking our daughter to see the Lord of the Rings trilogy on the big screen for the first time. The critic in me may have been feeling sheepish for not taking stock of the latest cultural offerings, but I had new reasons for turning to old comforts.

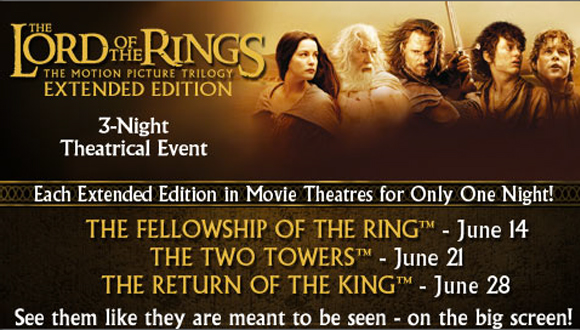

The screening of Peter Jackson’s films was especially interesting in this regard. Showing one time only at selected multiplexes around the United States, on Tuesday nights at 7pm — the third installment Return of the King is still to come on June 28th — they are the most recent example of a crucial shift in the distribution of mass culture.

The idea of a repertory is nothing new, of course. Theatrical troupes, opera companies and rock bands all have to strike a balance between new and familiar content, with the latter usually tipping the scales towards the past. Colleges and art houses have been screening older films for decades. And television has long relied on reruns to fill in programming gaps.

What’s different about this reprise of the Lord of the Rings trilogy is that screenings were taking place in so many locations simultaneously. Their one-time-only character made them into an event. Moviegoers didn’t have a choice of showtimes — it was Tuesday at 7pm or nothing — and had to leave their homes to convene in a public setting. But this event was also an example of coordinated mass distribution of a product that, because it was digitally projected, was functionally identical at each and every location.

Walter Benjamin’s famous thesis about the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction applies here, but with a different emphasis. Because what these screenings demonstrate is the degree to which not only cultural artifacts, but cultural experiences have lost the singularity that imbued them with an aura. Seeing a film from ten years ago at your local second-run movie theater may not seem all that different from seeing it at the multiplex of your choice — we had several options to choose from in Tucson, a city of some 500, 000 inhabitants — but the decoupling of time and place that occurs in the latter case is profoundly significant.

The technology that makes it possible to duplicate a singular event in this way, letting audiences experience films as if they were one giant crowd dispersed over a vast territory, is also the technology that has driven the biggest viewing trend of the past decade: the move from passive reception of one-size-fits-all programming — a fundamentally Fordist relation to mass culture — to active control of scheduling via “on-demand” services and recording devices — a perfect example of what David Harvey calls “Post-Fordism” transposed from the domain of production to the domain of distribution.

It’s interesting, then, that consumers’ preoccupation with getting greater control over media content is being tempered by situations in which they willingly surrender some of it in order to be part of a collective undertaking. The feeling of solidarity that we get as part of an audience for a one-time-only screening is the dialectical complement to that sense of individual mastery that comes with being able to choose when, how and on what devices we watch something.

Fathom Events, the promoter for these Lord of the Rings screenings, is the most prominent example of a business model that has grown up through the cracks in the twentieth-century Culture Industry. Up until now, most of their attention has been devoted to high-definition broadcasts of live events, such as performances by the Metropolitan Opera. By expanding to encompass cinematic repertory, they are reinforcing a development that has been underway for some time throughout the arts.

If the distinction between “high” and “mass” culture is largely a question of access, as Benjamin suggested, then enabling people to see the former at a fraction of the cost significantly blurs it. At the same time, turning movies meant to play round the clock for weeks on end into one-time-only events gives them a new prestige.

In both cases, though, generating the audiences necessary to make this interstitial venture worthwhile depends on placing safe bets. The Metropolitan Opera broadcasts that bring the most viewers into the multiplex are those featuring the proverbial old warhorses of the repertory. By the same token, it’s no accident that the Lord of the Rings films were given the special event treatment.

Not only were they wildly successful in their initial theatrical release in the early 2000s, but the core audience for J.R.R. Tolkien-related material has remained strong in the interim. Fathom Events could bank on the summer screenings being a success even without the benefit of the media coverage that first-run movies receive. Once a few Tolkien fans got wind of the screenings, word of mouth — or, to be more precise, its social media equivalent — would take care of the rest.

As someone who was excited to have the opportunity to see The Lord of the Rings on the big screen again and even happier that I could bring my daughter along, it would be disingenuous of me to portray the experience in a negative light. I would have gladly paid a good deal more for the pleasure the films have given me this time around. But that doesn’t mean that I’m oblivious to the troubling aspects of this development. Because if it’s only safe bets that receive this treatment, novelty will become more and more scarce in the cultural marketplace. Why pay $10 to see a new film I might hate, with an audience filled with disinterested texters, when I can pay a few dollars extra to see one I know I will enjoy with people who share my enthusiasm?

When I first saw The Fellowship of the Ring, the first film in the trilogy, in a movie theater back in late 2001, I was surprised and moved when the audience spontaneously clapped. The Two Towers got a similar response when I saw it in late 2002. And The Return of the King, which I saw on opening night in a theater rife with anticipation, actually outdid its predecessors, receiving a ten-minute standing ovation.

At the time, I thought it a little strange for the audience to express its appreciation in this way, since none of the people who made the film could hear the applause. But what I later realized is that people were really clapping for each other, acknowledging the courage it takes to suspend disbelief and immerse yourself wholly in a fictional universe with lots of people you don’t know.

It didn’t shock me, then, when the 2011 screenings were also met with applause. The audience clearly felt the need to repeat the fondly remembered ritual from before, as well as reconfirm its commitment to the films. But I couldn’t avoid the impression that this form of self-congratulation was also a way to vote for the safety of the past over the uncertainty of the present. The trilogy may have been the product of dark times, from the aftermath of 9/11 through the Iraq war, yet that period is now starting to glow in the light of nostalgia compared to the dire circumstances prevailing today.

I’m the last person who should argue against the exercise of nostalgic impulses, given how often I let my own run wild. Nevertheless, I have to wonder whether the desire to relive past pleasures — and to do so in the safety of numbers — isn’t threatening to transform the cultural arena into a space where we can learn more about what we already know but very little that is truly new.