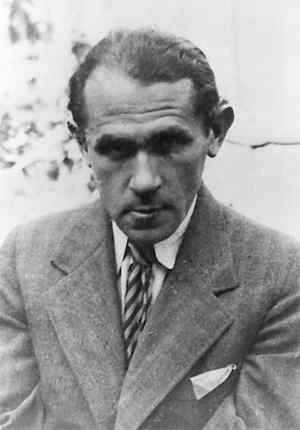

Bruno Schulz was a genius. He invented his own language and sensibility. His narrative style and its fantastic voice create a complex reality, much like the piled-high small shops he describes. Schulz has been mislabeled ‘the Polish Kafka,’ a mistake because Franz Kafka had a far more specific social vision that addressed relations between citizen and state. For Schulz, the subjects were self, family, neighbors and the cityscape surrounding them all. His best-known work, The Street of Crocodiles, repeatedly articulates a sense of foreboding. The darkening city and its directionless, rushing crowds provides a cautionary metaphor for a society that does not know where it is heading.

It is this question that interests, especially today. While we can trace Schulz’s influence within Jewish literature – Cynthia Ozick, David Grossman – and European and American literature – Danilio KiÅ¡, Bouhamil Hrabel, and John Updike, to name the better-known writers – the larger question resides in how fiction engages with society. How does storytelling grapple with emerging ideologies? How can it struggle against a coming catastrophe? While it’s easy to read fiction as a historical mirror, the more difficult issue lies in understanding how it works, in its own time, to comprehend danger. Pursuing this question does not indulge in a deterministic view of fiction as a social crystal ball, turning it into an object whose predictive usefulness can be understood if we gaze at it sufficiently. Rather, we recognize one function of storytelling lies in the work of social exposition and resistance at a specific time and place. The politically neutral story has yet to be written: all narrative is political. Given a sense of social danger, the question becomes how storytelling resists.

Schulz employs surrealism as a mode of writing amenable to historical foreshadowing. Often we understand that terrible events are going to happen before they transpire. We perceive sources of social violence and comprehend their threat, but do not know how such threats may come to realization. The surreal and its search for intensely colored metaphors and expressive language that supersede the ‘normal’ represents one approach that attempts to pursue such searches for what today is unreal but tomorrow may be real.

The fiction that Schulz began publishing in 1934 coincides with a period of intensification of European nationalism and racism. Schulz was a Polish-language modernist in a Jewish community headed for virtual extinction in its home territory within the coming decade. A death-culture was on the march, one based on historical revisionism, militarism, exclusionary concepts of civitas, and denial of entitlement to life itself. In less than a decade Schulz himself would lie dead in a Drohobych street, shot dead by a Gestapo officer. Jerzy Ficowski, Schulz’s leading biographer, suggests that the writer’s “entire life was overshadowed by his intuition of imminent danger.” Yet, though we can almost smell the danger coming off the pages, like most Polish Jews, there was no running away for Schulz. His life was so deeply embedded in Poland’s Jewish community that there was nowhere else to go. Schulz never left Drohobych, a Galician town of some 35,000 at the time, even after publication of The Street of Crocodiles in 1934 brought him national notice and radio readings of his work. Ability to discern does not translate into ability to act.

The Polish-Jewish literary milieu where Schulz published was a mixed, polyglot affair. Jews wrote in Polish, Yiddish, and Hebrew. Some wrote in German too, as did Schulz in a few essays. Writing careers were conducted often in two or three languages, switching back and forth depending on audience, forum, or expressive need. Schulz, a high school art teacher in a provincial city, did not align himself with any group: he was a creative isolato who had assimilated into the Polish language. His family had lost connection to Jewish languages. In terms of Jewish-language literatures, he had no connection with the Yiddishist circles of Warsaw where Israel Joshua Singer and his younger brother Isaac Bashevis Singer socialized. Yiddish modernism and its revolutions lie entirely distant from Schulz’s sensibilities. In terms of Polish literature as a whole, Schulz did not share the social realism of contemporaries such as Zofia NaÅ‚kowska or the sharp, satirical anti-romanticism of Witold Gombrowicz, even as he admired their work and shared friendships with both writers. He cannot be said to have had any significant effect on post-war developments in Polish literature.

There is alienation manifest in Schulz’s writing that does not lend itself to framing social messages. Unlike the major projects of Polish, Yiddish or Hebrew modernist fiction, Schulz seems to deal with the world by escaping its gravity. He writes less to illuminate mysteries than to wander abroad among them. This is not mythification of the dilemmas and paradoxes of Jewish folk life, as in Isaac Bashevis Singer. Nor is it the class – and gender -cognizant fiction of Esther Kreitman, the older sister of the Singer brothers. Rather, it a prose that transforms the experience of family, friends and townspeople into a source of phantasmagoric wonder. During a decade when socialist realist fiction propagated itself across Europe, the Americas, Asia and Oceania, Schulz writes in a way that questions the solidity of materialism. He animates objects into conversation with each other; he transforms humans in supernatural fashion. The family shop and its fabrics are a continual source of transformative imagination.

There are no explicit politics, but the politics are inescapable. Schulz’s prose is a theater set for acting out improbable, impossible dreams. Scenes change magically, shifting in apparent random sequence headed toward an unknown narrative horizon. Neither are there discernable links to the cosmopolitan western European surrealism of Andre Breton, Louis Aragon, Frederico Garcia Lorca, or Antonin Artaud, all of whom embraced radical left political movements to one degree or another. These were surrealists with answers and challenges; Schulz offers questions and strange dreams.

The Street of Crocodiles takes the form of an autobiographical novel, one might even say an autobiographical reverie. Its original form was as a series of letters to writer Deborah Vogel, with whom he maintained a close and possibly romantic relationship. Most of these letters disappeared, so we do not know the full extent of the stories they contained.

When Zofia NaÅ‚kowska, a major figure in Polish intellectual history, read the Schulz letters she praised their innovation and aided in arrangements to publish a book based on the letters. Their stylistic innovation within Polish literature, as important as that may have been to a Polish readership, seems today secondary to the dark spirit hovering over these stories. If the characters behave strangely, the European society in which they live – and Schulz so often mocks – is far stranger, much more dangerous, and its national fascisms will prove fatal to tens of millions.

These stories satirize the romanticism that has fed the social myths of Polish society for generations, causing them to disappear. Noble gentlemen in military uniforms are no more here than jackets on parade, to be conjured up or wished away. The spiritual symbols of Polish society – most especially the Catholic church – hold no sway in this fiction. It is an urban bourgeoisie and its nightmares that matter here, not the remnant anti-modern aristocracy, the Church and Christian triumphalism, or the subordinated peasantry and industrial working classes.

This is a Polish world in which there is a new and pervasive disconnection between objects and their symbolism, where reality has acquired a magic mutability. The resulting dark world is deeply disturbing to Schulz and the characters populating this text. In a brilliant passage from the ‘Visitation’ chapter, the father sits to work:

“While he sat there in the light of the lamp among the pillows of the large bed, and the room grew enormous as the shadows above the landscape merged with the deep city night beyond the windows, he felt, without looking, how the pullulating jungle of wallpaper, filled with whispers, lisping and hissing, closed in around him.”

The shadows of the outside defeat the light within the bedroom; the night surrounds and threatens his father with barely-heard voices. Danger is palpable even if its immediate source is not. Night gloom threatens to consume all light. Soon the inhabitants of this world will no longer be able to see. Similar preoccupation with the night occurs in Sanatorium under the Sign of the Hourglass, as in the ‘Night in July’ chapter. Whether it is “an enormous black rose, covering us with the dreams of hundreds of velvety petals” or “a night train, long as the world, driving through an endless black tunnel,” Schulz continually searches through a dense series of metaphors that luxuriate in darkness. Here “The dead matter of darkness sought liberation in inspired flights of jasmine scent…” There is a sweetly rotten attractiveness to the night, one that draws in the sense. For Schulz, the night itself is alive and dreams animate its endlessly expanding shell.

In the world that Schulz describes there are no inanimate objects. All matter contains life; all matter may be vivified at any moment. The shop and the town buildings hold as much life as their inhabitants. “There is no dead matter,” the father teaches in the first ‘Treatise on Tailors’ Dummies’ chapter, “lifelessness is only a disguise behind which hide unknown forms of life. The range of these forms is infinite and their shapes and nuances limitless.” Life itself is open to invention. The third ‘Treatise on Tailors’ Dummies’ concludes with the imagination of “a species of beings only half-organic, a kind of pseudofauna and pseudo-flora, the result of a fantastic fermentation of matter.”

These new beings are to be found in “old apartments saturated with the emanations of numerous existences and events; used-up atmospheres, rich in the specific ingredients of human dreams; rubbish heaps, abounding in the humus of memories, of nostalgia, and of sterile boredom.” Life, in short, lies not in noble romantic imagination but in pedestrian dreams and fears. There is no class dividing line between lifelessness and life. Rubbish, dreck and destroyed dreams are the stuff of new life.

Such preoccupation with new forms of life and death speaks to a culture where the unimaginable would shortly become the everyday. This is the language of premonition where senses are trusted only to the extent they caution and warn, where the unbelievable becomes the mundane. Surreal language provides a statement of the impossible realized, of nightmares become hard fact materialized. For Schulz, European history, and its received meanings die in these horror-filled dreams.

In the concluding section 40 of ‘Spring,’ for example, Schulz names “once-splendid men, the flower of mankind” whose nineteenth-century names speak either an emancipation or national unification. He begins with the pair of Dreyfus and Garibaldi, a fascinating combination of Jewish cultural resistance and Italian liberation, and then names Bismark, Victor Emmanuel I, Gambetta, Mazzini and finally the doomed figure of Archduke Maximilian. It is this comically-armed cohort that follows the narrator Joseph in the dream as he seeks to liberate the dream-figure of Bianca, an image of white femininity.

European nationalisms join with failed imperialism (Maximilian) in this topsy-turvy chapter of the Wax Figures exhibition exploding, assassination, and toppling reigns. Schulz distrusts nationalism and republican old guards as unredeemable figures, but the character of Joseph seems to find no escape by the end of this chapter sequence. A military officer prevents him from committing suicide on the spot and arrests him, dragging Joseph away in handcuffs before he can kill himself. In the dream-world Schulz writes, even death has no power to avoid the sight of on-rushing catastrophe.

Joseph’s father embodies a generational end-time. The father, family house, and shop seem as one. Where the son fabulates to understand the world, his father rationalizes to the same end. His is the final generation to live their full lives in Drohobych, a future that he somehow perceives but does not comprehend. “He was the last of his line, he was Atlas on whose shoulders rested the burden of an enormous legacy. By day and by night, my father thought about the meaning of it all and tried to understand its hidden intention.” Schulz compares his father to a biblical patriarch, a shepherd moving both sheep and “that swarming, homeless Israel.” Father can bring financial prosperity and has business acumen that keeps the shop a profitable concern, but in the end he is as lost as all the characters populating these narrated dreams.

The fabulation of dreams cannot provide safety, for as Schulz writes in the short, powerful and revealing “Republic of Dreams” sequence, dreams capture central truths that materialism and empiricism cannot. “Nothing happens here by chance,” Schulz writes, “nothing results without deep motive and premeditation. Here events are not ephemeral surface phantoms; they have roots sunk down into the deep of things and penetrate the essence.” Such outlandish dreams react against a social toxicity, one whose poison spreads throughout the town. The shop cannot serve as refuge; it is not a fortress.

Although “We dreamed the region was being threatened by an unknown danger, was permeated by a mysterious menace,” the dreamers of good will are powerless against packs of wolves and highwaymen in the forests. Dreams warn; they do not defend by themselves. Rather, Schulz cautions, “Embedded in the dream is a hunger for its own reification.” Dreamers must be careful to distinguish between their own desires and the social realities from which dreams derive interpretive power. There is no escape from the modernist nightmare that Schulz describes. No pleasant and warm dream, and no refuge dream. Yet, at the same time, Schulz sees no viable course other than to dream of another world to come: “We are all of us dreamers by nature, after all, brothers under the sign of the trowel, destined to be master builders.”

Schulz’s complex and contradictory engagement with dreams serves as warning, liberation, and shared human destiny. It is difficult to read Schulz without a sense of foreboding, without an understanding of it as mistily pre-apocalyptic fiction. Post-war European and American fiction would bring a far different, sharper and more realistic sensibility of post-apocalyptic modernist writing. John Hersey, Ray Bradbury, Judith Merril, Neville Shute, Pat Frank, and others wrote about genocides and worlds disappearing, whether in witness accounts, fiction or science fiction, with an intense awareness of immediate past history and future possibility.

Schulz’ surrealism was a secular expression of foreboding, an expressive locale he shares with Michael Chabon’s envisioning of new Jewish disasters in The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, or Gary Shteyngart and Super Sad True Love Story’s vision of a post-imperial America in violent collapse. Schulz and his surreal dreams lived in a more innocent age of Jewish fiction when the full extent of violent possibilities remained unimaginable.

Bruno Schulz photograph courtesy of Wikipedia.

An interesting interpretation, though the relevance of later west-Euro writers is redundant. But care should be taken: Schulz did not write any books entitled ‘Streets of Crocodiles’, it was ‘Cinnamon Shops’ and the translator transgressed immorally by changing it. Also it is an extremely faulty rendition, with too many mistakes and even additions not present in the original. See Brian R.Banks’ ‘Muse & Messiah: The Life, Imagination and Legacy of Bruno Schulz’ (2006) about this, and also Ficowski’s liberties.