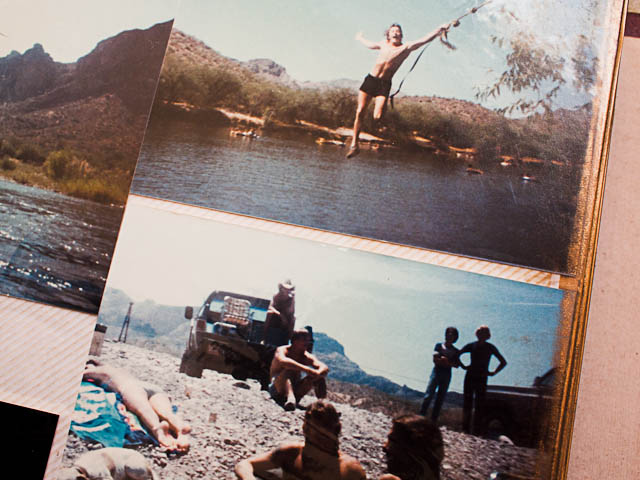

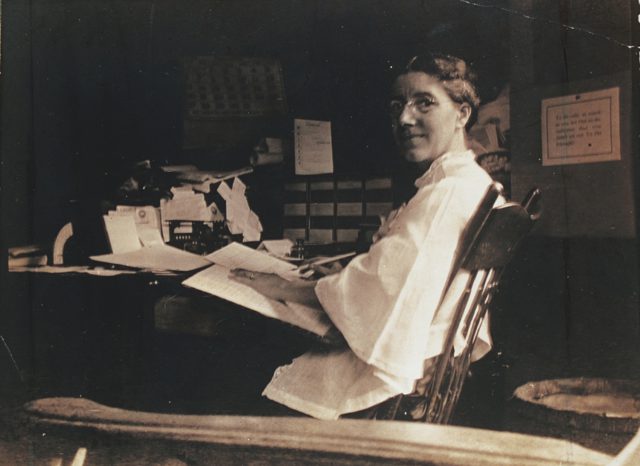

When coming across photos of anonymous people, it is impossible not to relate them to our own lives and memories somehow. Often we have an intense positive or negative response to the people looking out of these photographs and the history they represent. The universality of life represented in the photographs — birthdays, weddings, family vacations — crosses economic and gender boundaries.

What we see in photos are events of life and the emotional record of those events. Traces of personal identity become blurred with our own relationship to the events. When mixed with stray media and the used-up commercial trappings of life, the photographs give us a way of placing ourselves, if only by contrast, within the messy world that we inhabit where self-image, sexuality, and love are major factors that define us.

When my collaborator Kim Nicolini and I are out working on our Copper Belt Project, ignoring No Trespassing signs, pushing our way through broken doorways, climbing under barbed-wire fences and finding any point of entry we can into the numerous deserted buildings that we explore in the withering copper-mining towns of Central Arizona — Clifton, Globe, Hayden, Miami, Safford and Superior — the places we find may be abandoned but they are far from empty. Besides furniture, appliances, television sets and clothing, we come across many intimate personal artifacts that have been left behind.

The haste of most departures in this region is driven by economic desperation. Many things are inadvertently forgotten or simply abandoned because there is no means or time to move them. Foreclosure comes down fast. It is not unusual to find personal scrapbooks and photographs strewn amongst the random stray personal belongings. The photos left behind provide evidence, a partial record, of the people who are now gone forever from the premises.

Kim and I saw the little white stucco house with blue trim sitting on the edge of a hillside while driving down Smith Street in Miami, Arizona. The front steps were being taken over by a few Trees of Heaven. These are referred to as ghetto-trees in Detroit because they are able to quickly invade and damage any unmaintained structure, something that Detroit has a lot of.

Ascending the front steps to the house was somewhat frightening as the ghetto-trees had already undermined the front porch, and the stairway was slowly being ripped away from the house. To enter through the front door, we had to jump over a large gap in the unstable broken wood landing.

Inside the house, though, the rooms were bright, airy and remarkably clean. It almost felt like a broom and a few cans of paint were all it would take to turn this into happy new home overlooking the large copper mine across the valley. Matched coffee cups sat on otherwise empty cupboard shelves. Vines grew through the cracks in the window. It reminded me of the cozy house my grandmother lived in.

Half-packed boxes sat in the rooms. An ornate birdcage rested on a chair by the door, as if it had been left behind years ago. Someone had rifled through boxes that had been left in the living room, probably looking for items of value. Clothes and children’s toys were thrown to the sides of the room. A few stray photos were strewn on the floor. We bent down to look more closely at the photos, and that’s when we found a photo album sitting by a box.

The photos in this piece are a selection of the ones we found in that album, presented as we found them and are in no way attempting to pass judgment or draw conclusions regarding the people who are pictured or of their lives. These photos are unremarkable snapshots of working class people taken to preserve memories of their lives.

Both Kim and I looked through the photographs and reacted emotionally based on our individual pasts and how the people in the photos seemed to connect with our experiences. We were only voyeurs, with no connection to them or their photographs, yet we both had intensely personal responses to the photos. From our detached perspective, it was — and still is — easy to project our own lives onto the images, to see in the faces of these people we never knew distant family members, first boyfriends, past tormentors and perhaps even old friends and acquaintances.

But it’s important to remember that all these people had their own lives, emotions and histories that we know nothing about. Every single one of us experiences love, happiness, anger and sadness. We all have our own snapshots to share, but personal experience is not chained to photographs. Even when a photo album is lost, our memories and emotions still remain.