Punk begat ska and ska begat a rainbow. Two-Tone, New Romantic and a slew of pop artists shone out of the darkness of early Thatcher Britain with lyrics and beats that ran the gamut from escapist to confrontational. Many bands have been discussed in print and film, but no one has yet noted the surprising similarities and radically different paths of two male duos, formed thirty years ago from the flotsam of the ska movement. They charted different paths. But both paths took them to the pop charts.

Graduating from the short-lived school ska band The Executive, George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley went on to form the headline-grabbing and record-breaking Wham! From 1981 until their breakup in 1986, they were one of the most important pop artists in the English-speaking world. Michael’s hugely successful solo career (not to mention his checkered personal life) has guaranteed his back catalog a continued limelight.

Also thirty years ago, another duo emerged from a ska band — The Graduate , named after the 1967 film starring Dustin Hoffman and Anne Bancroft — that existed long enough to sign a record contract and even release an album on Precision Records, Acting My Age. The chirpy single Elvis Should Play Ska, sounded a lot like its subject, Elvis Costello, and only just failed to reach the British Top 100. From this unlikely beginning, Roland Orzabal and Curt Smith formed the thoughtful new wave electronic band Tears for Fears, whose ’80s hits included three platinum albums The Hurting in 1983, Songs From the Big Chair in 1985 and Seeds of Love in 1989, as well as a cult following that endures to the present day.

The styles and impact of the two bands could hardly have been more different. However, despite their differences, they were both a profound part of a 1980s pop culture whose acts, and especially the songwriting of Michael and Orzabal, embodied a response to Thatcherite individualism. Those ties endure through the ska connection. Andrew Ridgeley’s life partner is Keren Woodward from Bananarama, who were discovered by the post-Specials ska group Fun Boy Three. Nicky Holland acted as Fun Boy Three’s musical director before going on to play in the supporting band on a Tears For Fears tour and becoming Roland Orzabal’s songwriting partner.

Tears for Fears was named for Arthur Janov’s idea of psychological treatment of neurosis through “primal therapy.” And, in an unprecedented move for a successful pop group, Smith and Orzabal consistently used ideas from Janov’s The Primal Scream throughout a decade of success. In stark contrast — as suggested by the onomatopoeia and punctuation included in the band’s name — Wham! was committed to impact, celebrity and a flexible attitude to hedonism.

When Wham! got its first break, neither Ridgeley and Michael were yet 20. A slickly choreographed appearance on bellwether British music show Top of the Pops in 1982 was enough to push their second single “Young Guns (Go for it!)” into the Top 40. They never looked back. Along with Wham Rap! and “Bad Boys,” “Young Guns” turned the group into a top ten fixture with a mixture of ska-inflected dance music and early British rap. During this time, the bad boy duo mocked the bourgeois ideal of jobs and marriage, espousing instead a commitment to fun. “Wham Rap!” was tellingly subtitled “Enjoy What You Do” and it gave instructions: “Give a wham, give a bang, but don’t give a damn / Cos the benefit gang are going to pay!”

The release of “Club Tropicana” in the summer of 1983 marked a change of direction for the band. Though intended as a parody, the notes of protest from the earlier singles (“You got soul on the dole / You’re gonna have a good time down on the line”) were gone from this single. Indeed, in a strange feat of identification, the video and photoshoot of Michael and Ridgeley in Ibiza, mocking the fantasies of cheap package holidays in Spain and Portugal, left them with the image of the quintessential good time boys.

Happy-go-lucky playboys was the image that would stay with them until they split up in 1986. During that time, they became vastly popular and even played an important gate-opening 1985 concert in China. Increasing international fame, however, had been accompanied by a mellowing of message. From a youthful tone of confrontation and social entitlement, Wham! had softened into the simple sentiment of romance: “I don’t want your freedom, / Girl all I want right now is you.”

Judging Wham! on their analytical content is blatantly unfair. There were many other English pop groups and musicians for whom social critique was more important — Billy Bragg and Paul Weller on politics; Boy George, Marilyn and Pete Burns on sexuality; Joe Jackson and Elvis Costello on social mores. Even in their early songs Wham! had only a tangential social critique to offer. But it’s worth bearing in mind that, given their roots and beginnings, Wham! could have taken a very different path.

And Tears for Fears did.

Although by 1989 Smith and Orzabal were making their feelings known about the political situation (“Politician granny with your high ideals / Have you no idea how the majority feels”), for the majority of the decade they were resolutely fascinated by the workings of the human psyche. Their foot-stomping 1984 hit, “Shout” is, surprisingly, a succinct, forceful and highly catchy description of Janov’s theory. Where Janov observes a “scream… as the product of central and universal pains… [which] Primal Therapy is aimed at eradicating,” Tears for Fears tell us to “Shout, shout, let it all out, / These are the things we can do without.”

Janov’s basic theory is that adult neuroses, including a desire to ostentatiously display importance (“Everybody Wants to Rule the World”), come from traumas suffered during childhood (as in the song “Suffer the Children”). Neither talking nor medicating provide effective cures. Instead Janov advocates “overthrowing the neurotic system by a forceful upheaval.”

These ideas provoked a drastic change from their cheeky, Graduate-era demeanour. Orzabal and Smith emerged as brooding, electronic distance-gazers in Tears for Fears’ debut album The Hurting which is a prolonged scrutiny of a psychologized melancholy. It poses depressing questions from start (the opening words of the title song — “Is it an horrific dream? Am I sinking fast?”) to finish (the album’s closing words from “Start of the Breakdown” are “Is this the start of the breakdown? / I can’t understand you”). And probably the most famous phrase from the biggest hit of the album, “Mad World,” is “The dreams in which I’m dying are the best I’ve ever had.” This all seems to promise unmitigated gloom, but the application of Primal Therapy seems to suggest that there is hope: in the words of “Change” — “you can change.”

Though Orzabal, who wrote or co-wrote Tears for Fears songs with a variety of co-writers, has claimed that “Shout” is a more general protest song and was moving away from Janov by the time of Songs from the Big Chair, the lyrics were still closely associated with psychotherapy. The name of the album comes from Sybil, the 1976 film featuring Joanne Woodward. In it the protagonist comes to terms with her multiple personalities. The analyst’s “big chair” is where she feels most comfortable. Samples of the film dialogue were placed in the atmospheric song “The Big Chair” which was included in a remastered and extended 1999 version of the album. And, right at the heart of the album, comes the heart-wrenchingly frank “I Believe.” As an explicit credo it doesn’t come much closer to Janov than:

“I believe that when the hurting and the pain has gone

We will be strong.”

It would be overly simplistic to plot the three albums in turn as diagnosis, treatment and cure, but the trend is evident. Introspection on “The Hurting” becomes the strident faith of “Mother’s Talk” and “Shout” on Songs from the Big Chair, before becoming the celebration of “Sowing the Seeds of Love” and “Advice for the Young at Heart” on Seeds of Love. There are exceptions that seem to come out of sequence, such as the joyful “Head Over Heels” on “Songs from the Big Chair” and the forceful “Change” on The Hurting. However, the public and lyrical avocation of a decade of introspective primal therapy is evident.

Although there were grim domestic events noted by musicians in 1980s Britain, the defining moments of British pop music during the decade were outward, not inward-looking. Namely, these were the immense undertakings by the Boomtown Rats singer Bob Geldof, and Ultravox’s Midge Ure on behalf of African famine victims: Band Aid in 1984 and Live Aid in 1985. Both Wham! and Tears for Fears appeared in the former, both members of Wham! appeared in the latter. Though they pulled out of Live Aid at the last minute, Tears for Fears provided the theme tune for Sport Aid the following year courtesy of an appropriately re-worked “Everybody Wants to Run the World.” 1980s British pop would be unthinkable without these two groups but, whereas it would be difficult to find the ideology of Wham!, it remains a strange oversight that the theory behind Tears for Fears has been so consistently overlooked.

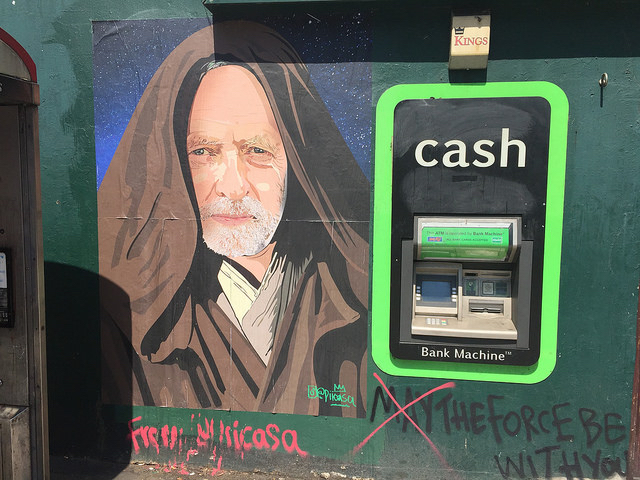

Photograph courtesy of Thomas Hawk. Published under a Creative Commons license.

This article had me enthralled! For all the difference between those bands, I’m a huge fan of both, with a preference towards Tears for Fears. To sum up, Tears for Fears are good enough to listen to anytime, whereas for Wham!, it depends on my mood. I don’t think Tears for Fears are overlooked and to me they are equals to the likes of Depeche Mode, etc.

Now one thing… don’t underestimate Wham!’s ability for social commentary, even if they did it in just one song, “Everything She Wants”. The story told by George Michael in those lyrics, that of a man struggling to make both ends meet and caught in a spiral of debt, makes it fit well within the Thatcher years when it became increasingly common for households to struggle with poverty. And if you look at the direction the world has taken… the debt issue was a huge one, George Michael and Wham! were really onto something when they made that song.