Besides mole and embroidery, Oaxaca is known for the Guelaguetza, an annual dance festival sponsored by the state and federal governments. The festival takes place in an enormous glaring white pavilion on the green hillside overlooking the city. The odd structure looks like a giant nun’s wimple fluttering in an updraft. It’s strangely menacing, as if just descended from the heavens, waiting to conquer the city.

On our visit to the carpentry collective, Antonio pointed out the construction crews working on the highway along the hill. He clicked his tongue and waved his hand. “This happens every year before the Guelaguetza,” he told us. “They fix up the road for the tourists. But wait until you see the road where we’re going.” Indeed, once we get out of the city center, the side of the road has disintegrated into ravines of gravel. On this two-way road, cars must slow and pull aside to allow oncoming traffic to pass.

Thousands of tourists flood the city for the festival, most from other parts of Mexico but many from other countries. During the protests in 2006, the movement put together La Guelaguetza Popular, or the People’s Guelaguetza. Rather than seclude the celebration to the pavilion where guests had to buy tickets, the People’s Guelaguetza sent dance troupes snaking through the city visiting neighborhoods both rich and poor.

The word “guelaguetza,” I’m told, is from the Zapotec language. It means “sharing” or “gift-giving.” The practice dates back to pre-Hispanic times, when the communities of the region would come together to give gifts and entertain each other. The early guelaguetza emphasized reciprocity between tribes. After the conquest, the practice underwent syncretic transformation and merged with Catholic elements. It was revived in the early modern era, and has since become a celebration of indigenous culture. When APPO tried to organize a second People’s Guelaguetza in 2007, they were shut down by police. Several people were beaten and arrested.

The opening night of the Guelaguetza, Miriam and I met outside Santo Domingo where women in bright traditional outfits, their hair coifed in tight upturned braids, took pictures of each other in the church plaza. A crowd was gathering before the inaugural parade on Garcia Virgil. It was a familiar mix of gringos in sensible shoes, squealing teenagers, guys wheat-pasting a drawing to a wall, families strolling, toddlers toddling, and street vendors selling everything from rugs to balloons.

Being space cadets, neither of us bothered to buy tickets to the event, and missed it. However, we took in the parades, fireworks and crowds since they were impossible to avoid. A fews days later, we got a chance to examine the wheat-pasted graphic on the side of the building across from the church. It was an enormous dancer in indigenous costume and headdress. Inside his head, instead of a face, a little man in a suit was operating a control booth with old-fashioned levers.

****

The movement in Oaxaca coalesced in the city, drawing support across class lines, among the rural and urban poor, the working and educated middle classes. There, it faced ruthless repression that continues today. Many activists are still in jail. APPO seems dormant, but its marks are still apparent. Vendors still advertise their APPO branch with a laminated badge next to their wares. Smaller organizations, like APPO-VOCAL, the more anarchist faction of APPO, still exists, alongside indigenous rights groups. The fight for autonomy continues by varied means in the rural municipalities.

The most infamous story is San Juan Copala, a village that declared autonomy from the Mexican state in 1994. San Juan Copala is a Triqui village, one of the many indigenous peoples of the region. To make matters more complicated, Triqui villages have been controlled by a group called the MULT (Movimiento de Unificacion y Lucha Triqui) that nominally represents indigenous interests but in reality has been aligned for years with the PRI party, the de facto dictatorship until 2006. The MULT act as caciques, mafia-like local leaders who control rural areas under the authority of the ruling party. They also act as paramilitary forces when needed and have been linked to the death of many activists since the 2006 uprising. When the village declared autonomy, it was also declaring autonomy from its own indigenous tyrants. Leading the declaration was a group called the MULT-I — the “I” stands for “Independent.”

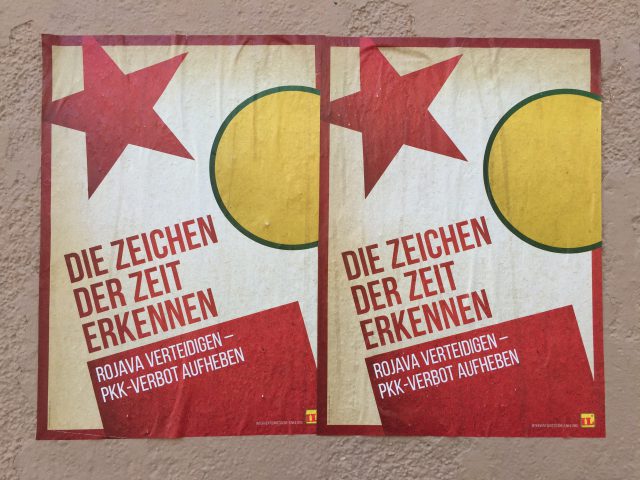

In April 2010, local activists bringing goods to a besieged San Juan Copala were murdered on the road by MULT paramilitaries. (Among the dead was an international solidarity worker from Finland.) A month later, the leader of the MULT-I and his wife were killed. In the spring of 2011, the MULT headman, Heriberto Pazos Ortiz, was murdered. His followers attest that it was a state assassination. Several banners and posters commemorated the slain leader were hung in the zocalo and around town. As I realized over my month in Mexico, the war between the MULT and MULT-I, like so much in Mexican politics, was a war over the symbols and language of revolution — both the revolution of 1910 and the coming revolution — and the right to speak for the people.

What was striking to me about Mexico was that unlike most of North America, many indigenous communities remain populous and conspicuous, having survived Spanish colonialism with their customs and languages intact. In the United States, disease, genocide and settlement have minimized visible remnants of Native American life. Indigenous peoples account for less than one percent of the population of the United States, where a fraction of Indian ancestry is considered Native American descent. They account for slightly less than ten percent of the population of Mexico, a country where an admixture of European ancestry will qualify one as mestizo, a racial category distinct from “indigenous” and with which, I’m told, most Mexicans identify.

The politics of indigeneity are complex. I don’t mean to oversimplify their nuances. Suffice it to say that in Oaxaca, as in Chiapas, the struggle for autonomy has acquired currency outside of the interests of the rural indigenous communities. It has intermingled with the fight against repressive government and the imposition of neoliberal economic policies and the struggle for free expression. The language of recognition and autonomy taps into a stream of anti-colonial sentiment that draws its power from the history of Spanish conquest, gaining relevance in the struggle against global capitalism. It’s a potent and incisive brew.

****

It was almost time for me to go home, back to California, and I dragged Miriam to a quasi-fancy dinner. The restaurant was not far from the Santo Domingo church. We were the only people in the dining room — maybe because it was the last night of the Geulagetza. On a fuzzy television hung on the wall, we watched the closing ceremonies with the wait staff who were standing around idle at the bar.

Broadcasting from inside the ominous nun’s wimple, gaily dressed women in bulky colorful skirts dance with men in simple white cotton, sombreros and decorative blankets slung over a shoulder. They danced barefoot, each pair hopping in a simple pattern that slowly twirled them around the stage, acting out courtship and marital bickering with smiles and laughter. The crowd was filled with people wearing typical broad-brimmed straw hats. The dancers throw more hats into the audience at the end of the number.

In the restaurant, the waiters leaned on the bar, watching the television, commenting to each other with broad smiles. One of them broke into a dance for the amusement of his compañeros just as the bell went off in the kitchen calling for him to bring out the food. He ran off in a parody of expedience as the others giggled.

Afterward, in the church plaza, we discovered a lively stage show of teenagers in traditional dress, a costume much like the dancers in the pavilion on the hill, dancing to a live band made up of a fiddle and brass. The Guelaguetza is still celebrated all over the region in its local incarnations. Apparently, Oaxaca City is no exception — as long as the celebration doesn’t explicitly align with antiestablishment politics. A crowd had gathered around the stage. Early birds had grabbed some seats set up in front. The young dancers wore simple sandals, slapping their feet in unison and bouncing and circling in careful controlled steps that reminded me of square dancing. (Perhaps the dances are related?)

The girls were young and slender. Their white blouses were tucked into colorful full skirts that swayed back and forth as they stomped and twirled. The boys were remarkably nimble. They wore colorful collarless tops and brimmed brown hats.

Together, their adolescent awkwardness and youthful enthusiasm were irresistible. We sat down to watch on the enormous steps descending the southern wall of the church. The massive greenish-yellow stones all around us were cast in a bronze hue by the stage lights.

Not long after, fireworks began to detonate from a nearby corner of the plaza. Since I arrived, the fireworks in Oaxaca have been constant. They begin everyday after sunset, sometimes even earlier. Often they’re just enormous booms, without lights. Oaxaca City would be a nightmare for anyone with PTSD.

Since the Guelagetza started, pyrotechnics and light shows have been more frequent. They took place in the two plazas — Santo Domingo and the zocalo — courtesy of the governor’s office. Each display required tons of equipment and, I would imagine, planning and budget. That morning, they had cordoned off a portion of the pedestrian walkway to set up the bundled canisters and tubing. When I came by this morning, I saw at least ten workers putting it together.

The fireworks drowned out the delicate clangy chorus of fiddles and footsteps. People glanced up in awe as the explosions cover the night sky. Soon smoke began moving towards us, and families deserted. Pieces of black char started falling from the sky — first the size of thumbtacks, then bigger and bigger. The smoke thickened as the crowd thinned, but the fireworks kept going, showering us with charred remains. People opened umbrellas. The dancers milled around on stage waiting for the display to end so they could start up again. Some had jumped down from the stage to watch.

Photograph by Joanna Steinhardt