It had been a long time since I’d visited such an unfamiliar country. I came to learn Spanish, but quit halfway through. I spent a day holed up in my apartment reading Fire and Blood and Teaching Rebellion, the book about the 2006 protests that I picked up at La Jicara. I didn’t know whether I was a tourist, a bad student or just a curious visitor. With only a month of time, minimal Spanish, and rudimentary knowledge, there wasn’t much I could do that would be useful. Perhaps I was thinking too much like an American, who needs to “use” her time. In the end, I just wandered and enjoyed.

Like an American, I shopped. I suppose in this way, I can never be an anti-capitalist. I was raised by single mother running her own food business. My father was a lawyer representing small business owners against specious urban planning. As a result, I appreciate honest labor and good products. I bought beautiful scarves from the street vendors, small bricks of local chocolate in the labyrinthine central market, embroidered shirts and stamped metal mirrors from the women’s collective. Miriam and I moved on the better mezcal, without the gimmicky gusano. We found a tiny shop in a back alley that sold organic varieties bought directly from the distillers.

I even bought a pair of combat boots from the Zapatistas during our trip to Chiapas. Remarkably sturdy and well-made, these were one of the best finds of the trip. I bet they’ll last me at least a decade. For those going for radical chic, they even bear an official EZLN stamp. And for the anthropologists, they’re quite the material artifact of global radical culture. The catch is that you need to go to San Cristobal to buy them.

We also met an array of artists, activists and travelers enjoying the city and its subculture. Most of the foreigners were from Spain and South America, with one or two central Europeans thrown in and then of course a few North Americans, our new Canadian friend included. The owner of La Jicara was South American, as was the woman from the CASA Collective. In the market on Saturday, an Italian sold kimchi flavored flat bread, calzones and delicious corn bread muffins, aided by a cute Cuban. But these ex-pats weren’t cloistered in their own world. They all drank, partied, and passed time with Oaxaqueños.

Our short trip to San Cristobal was educational. There, the locals and foreigners seem to exist on parallel planes, rarely mixing. Upscale cafes, yoga studios and curry shops seemed even more plentiful in this tiny one-story town than they were in Oaxaca City. In Oaxaca City, the expats mingle easily with local crowds, in bars, in clubs, in the gallaries, on the street. The town is too small to have room for separate subcultures but it’s big enough to have a middle class. Oaxaca City is a town where, it seems, everyone meets in the middle.

The stories of repression were depressing but still, at the risk of sounding naive, Oaxaca inspired me. I was reminded of the theory proposed by anthropologist David Graeber that the majority of revolutions are the product of an alliance between “the most oppressed” and “the least alienated” — in other words, between the poor, artists and intellectuals. This is definitely the case with the Zapatistas, Subcomandante Marcos, and the radicals from all ends of the globe that went to Chiapas to assist in the struggle.

Will it happen for Oaxaca as well? Although the movement in Oaxaca is dealing with similar issues, it’s a quite difference context than the what the Zapatistas confronted. This is a constant question for me. To what degree is middle class radicalism a refuge for subversives, for idealists and dreamers? To what degree is it a means of furthering “radical” politics? And how much does art matter?

Leaving Oaxaca, my sense is that it all matters, a lot. Art can never replace the simple tasks of political organizing, but it can manifest a collective identity and that, in and of itself, is invaluable. Good art enlivens. Even in the saddest symphony, the subject is always humanity, and that’s something we all share. This basic fact of communal life is one that seemed taken for granted in Oaxaca. At least more than in this wealthy, anxious place called the US.

More than the politics, the giant puppets and the street art, it’s the disarming warmth of the people that I’ll remember most about Oaxaca. The lack of pretension, the politeness, the joy of public celebrations — from the near daily parade to the near nightly fireworks — and the freedom given to children to run and play. Oaxaca appreciates life. Not empty time waiting to be filled, but life as inherently full, a story, a dream. Any resistance that comes out of the region will draw from this vitality. In the alliance of Graeber’s least alienated and most oppressed, this is something we might learn to cultivate in America.

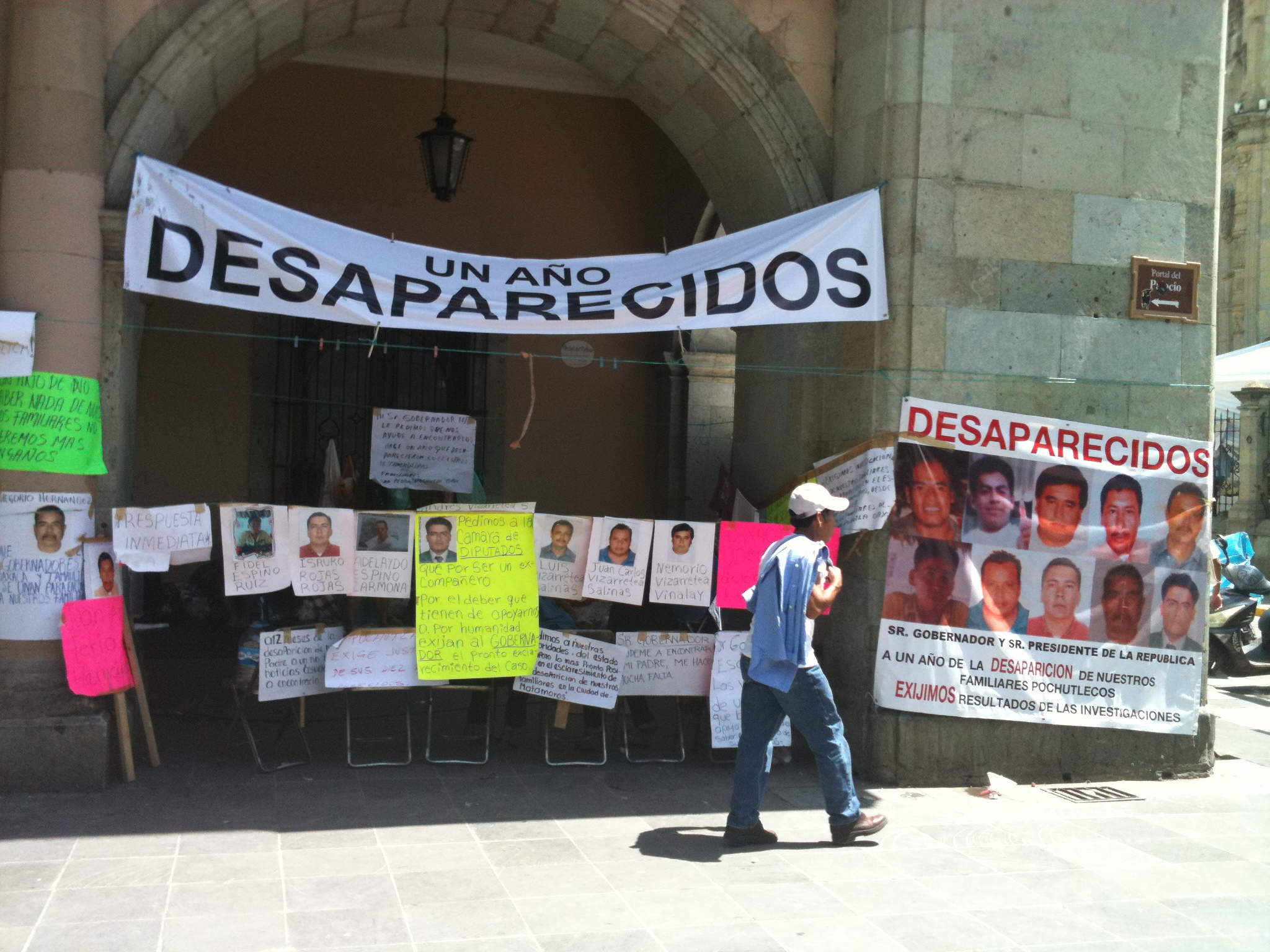

Photograph by Joanna Steinhardt