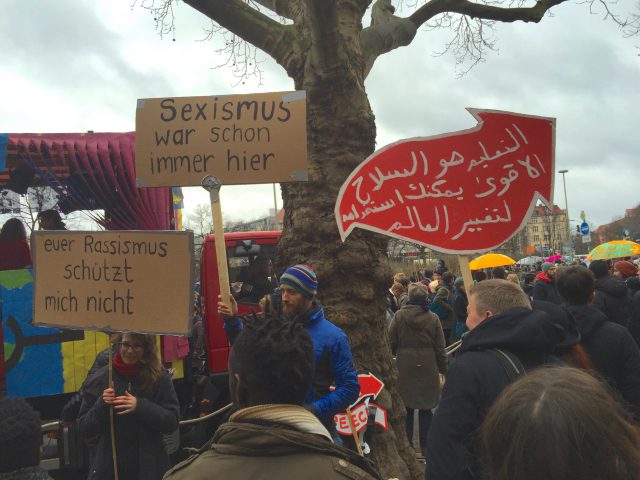

Antonio tells me that after the 2006 uprising, street art flourished. There are still signs of it flowering all over the city. I was fascinated by the fact that the street art in Oaxaca could pass muster in San Francisco. Clearly, the street art in both places flow from the same urban aesthetic. However, Oaxaqueño artists have developed their own local flavor.

Less distinctive are the full-scale murals that, as would be expected, mimicked what Americans would call the “Latino Heritage” mural. My visit to Mexico definitely gave me some context with which to understand to the prolific murals of the Mission District in San Francisco, where I lived for two years. Not to mention the populist murals that have proliferated throughout the Bay Area and other big US cities.

It would be interesting to know how much Oaxaca’s public artists are aware of street art in other cities, if they have traveled much outside of the country, and from who they get their artistic inspiration. Their work is self-consciously Mexican. For this, they’re lucky. With their country’s numerous pre-Hispanic cultures, the iconography of Catholicism, and a colorful pantheon of revolutionary figures, Mexican artists have a rich cultural canon to draw upon.

The same day I walked around admiring the street art, I visited La Jicara, a cafe and bookstore a little north of the center. La Jicara opened not long after the uprising. It was a radical bookstore with revolutionary intentions and a lot of anarchist literature, an art gallery and a somewhat incongruous upscale cafe. It seemed to cater to tourists visiting students and the small scene of local artists, activists and ex-pats. I felt at home, except for the mosquitos, which are attacking my bare calves in an avenging merciless swarm.

Galeria Espacio Zapata, down the street, is another spot that opened after 2006. It’s part of ASARO, an association of “revolutionary artists” that make art del pueblo y para el pueblo, by the people and for the people. Their studio space is spartan. There is a table up front selling colorful prints, stickers, DVDs, photographs and posters. Random bits of sculpture and a few paintings hang on the plain white walls. Racks of prints sit in a room off to the side. The subject is collective resistance, molotov cocktails, maize and the protection of local land from global capitalist greed. In the back is a printing press and drying racks. I chatted with a kid who was manning the shop, an artist with a lip piercing, a tight black t-shirt and mumbly Spanish that I could barely understand. He said he knew a girl in San Francisco. Her name was Jennifer; I don’t know her.

***

My friend Miriam has been in Oaxaca for three weeks studying Spanish. We agreed to meet in the zocalo, the enormous central plaza of the city. In the typical Spanish colonial layout, in the center of the zocalo is a huge church, this one dating back to the founding of the city in the 16th century. The zocalo is so large, it’s more like three or four plazas. The space was lined with touristy restaurants.

The zocalo is a meeting place, a resting spot, a stage, a market. It’s what the ancient Greeks used to call the agora, the vivacious embodiment of public life, in its beauty and ugliness, that is so rare in North America. Vendors sell clothes, scarves, balloons and fruit, laid out on tarps every few steps, in proper booths around the periphery, or sitting on the benches, their merchandise folding neatly in garbage bags at their sides, one plastic mannequin torso at the side clothed in a sexy elastic top of traditional material. Street musicians play xylophones, flutes, guitars and brass, some in bands, some on their own.

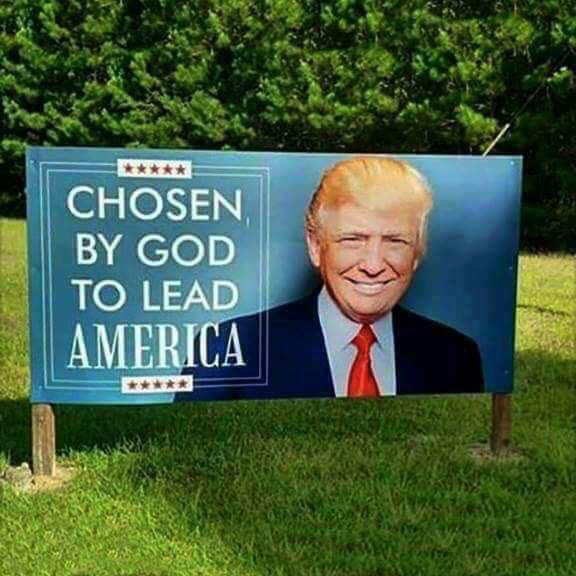

One small old man sung into a tiny amplifier with a sign set beside him proclaiming, simply, “AMO JESUS CRISTO.” A reused metal jar next to him collected pesos. Shoe-shiners shined the shoes of men or sat on their mini-thrones waiting for the next customer. Families strolled; young couples snuggled; little kids threw their new balloons into the air and waited, heads craning, to catch them on the way down. A tiny old woman begged. Other little kids sold wooden gadgets from pouches they slung across their small torsos. In the middle of the enormous plaza was a large wooden gazebo surrounded by small stands selling gum and cigarettes.

I discovered later that week that the Oaxaca Orchestra play free concerts every Sunday morning under the broad green branches of the trees next to the gazebo. At night, clowns draw enormous crowds performing outside the church.

***

By the time we meet, a downpour has begun and everyone is running for cover under the overhang at the edge of the plaza. The old lady begging for change has clothed herself in a garbage bag. The old man playing his tuba is unbothered, despite getting soaked. The well-prepared had opened their umbrellas, while the vendors scramble to gather their wares.

We walk past the tables on the sidewalk next to the restaurants protected from rain by the second-floor balconies. A soccer game has transfixed the wet masses, who stare up at the blue-green screens over the large oval plates of mole under the yellowish lights of the promenade. A glance at the crowd makes me think that many were visitors from other cities or other countries. We hear continental Spanish, some French and English. Little girls wear dresses of the distinctive multicolored local weave; their mothers wear the shirts in the local style, embroidered brightly around the collar with stylized flowers. Plastic shopping bags lie at the feet of their tables.

We splash through the rain looking for a place to eat. Miriam tells me that she’s been living on popcorn; I do not approve. Although she seems content to circulate in the pouring rain, holding her shawl over her head like a kite, I nudge her towards dinner. We find our way to a drafty restaurant on the corner of the plaza.

When she doesn’t know a word in Spanish, Miriam grins widely, turns her face to the side and taps her nose in a display of clownish contemplation. The waiter seems both bemused and intrigued by this behavior. She burst out laughing at her own attempts at language and signalled more confusion, pulling theatrical faces of embarrassment and self-parody.

After a bewildering exchange on the origin of the soup, she tells the waiter, “Sorry, I didn’t understand your joke.” He pauses and blinks, fascinated by this perplexing gringa. “I did not make a joke,” he says with an amused smile.

The fabled worm, or gusano, at the bottom of the glass of mezcal is in fact a large brown larva. Miriam eats it without chewing. I give her mine. She makes a face and swallows it.

Photograph by Joanna Steinhardt