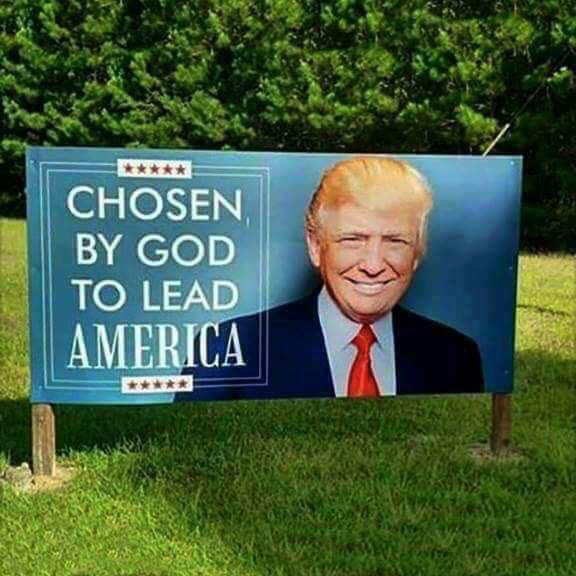

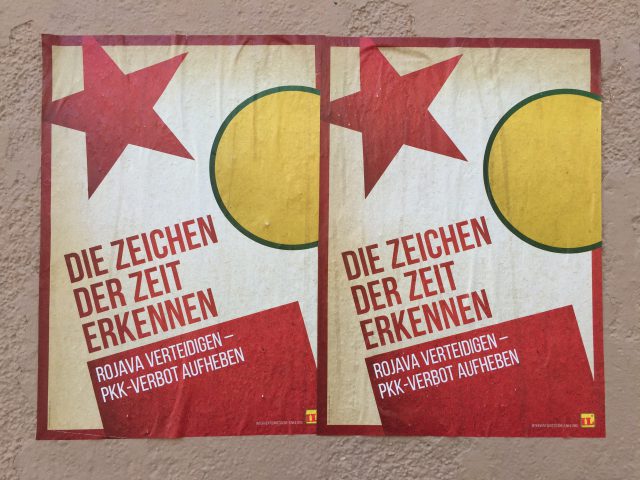

Spending time in the center of town, it’s easy to believe that Oaxaca de Juarez is a thriving, middle class city. However, if you pay attention to the details, even the most ignorant visitor can notice signs of discontent. Besides the street art, there’s the political banners hung in the zocalo, and the posters pasted on public phones and the ancient stone walls of the city. Street vendors are often as young as six-years-old. Some of these kids are barefoot, begging in local cafes.

I saw a child run into a cafe and crawl underneath the long wooden seats on which a gringo was sitting, pecking away at his laptop keyboard. After a few minutes, the boy scrambled out, and went underneath the bench lining the opposite wall. Everyone noticed him. A few people looked confounded. Others ignored the boy. The waiter took note but remained behind the counter, preparing a drink. After a minute or so, the child got out from under the seat and ran out of the restaurant, lost in his own world.

The state of Oaxaca is one of the poorest in the country. The poverty is concentrated in the rural areas distant from the capital. The outlying neighborhoods of the city feel like poor rural towns as well.

Besides the lack of work, public education is a serious point of contention. At an annual sit-in, teachers demand higher wages and better infrastructure. These grievances were the catalyst for the protests in 2006. However, the conflict that erupted became about something much bigger. It tapped into deep reservoirs of resentment amongst the general population.

Oaxaca and Chiapas, the neighboring state to the south, are home to one of the largest indigenous populations in the country. In Oaxaca, the main ethnic groups are the Zapotec and Mixtec, but there are an estimated fourteen more scattered throughout the largely rural state. These communities are underfunded and ignored by the government. They lack proper infrastructure, such as drivable roads, and a functioning water system. Indigenous languages, spoken by hundreds of thousands in the region, are largely unacknowledged by the government. (I had a baffling conversation with a cab driver in Mexico City who tried to explain why languages like Zapotec and Mixtec were “dialects” of Spanish rather than distinct languages.) The fact that children in these regions are learning in a second-language is an issue that the federal government has failed to address.

Since 1994’s Zapatista uprising, the struggle for indigenous sovereignty has gained momentum. Oaxaca is no exception. The issues of language, poverty and underdevelopment tapped into the demand for recognition and autonomy among indigenous peoples. It was a struggle that could be traced back most recently to the free trade agreements of the 1990s that flooded the local economy with cheap imports from the US. Yet, to many activists, it went back much further, to the arrival of the conquistadores five centuries ago.

It’s a familiar story to anyone who has paid attention to the Zapatistas. The insurgent group was led by Tzeltal-speaking Mayans in the vanishing Lacondian jungle in southern Chiapas. They declared war on the Mexican government on January 1, 1994, the day that the North American Free Tree Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect. After checkered success fighting the Mexican army, the Zapatistas retreated into the jungle where they have maintained an autonomous zone for much of the last sixteen years.

The Zapatistas have been enshrined as heros of the anti-globalization movement, in part thanks to the clever writings of their spokesperson, Subcomandante Marcos. The true identity of the Subcomandante remains hidden behind his balaclava. What was known about the man was that he was not Mayan but rather an educated urban intellectual. Thanks to his writings, the group’s strategic use of the Internet and their declaration of solidarity with the world’s oppressed peoples, the Zapatistas gained a global network of supporters. They became the symbolic face of a revitalized radical movement among disenchanted educated youth in first world countries — among people like me.

The uprising in Oaxaca was driven by similar grievances — poverty and neglect in the countryside, the lack of recognition for indigenous rights, the demand for greater autonomy — but it became a struggle against police repression, for free expression and the voice of the people. The city descended into violence on June 14, 2006 when state police targeted the teachers union’s peaceful sit-in in the zocalo with live fire and teargas. Passersby were caught in the crossfire. Over one hundred people were hospitalized.

The teachers were not to be deterred. They were now joined by tens of thousands of enraged, long-suffering Oaxaqueños who saw their city under siege by a despotic state governor, Ulises Ruiz Ortiz.

What transpired afterwards is best described as a popular uprising. Protestors built makeshift barricades around the zocalo, the central square and main streets. They were joined by numerous populist, leftist and indigenous groups and unaffiliated citizens. Together, they formed an umbrella group called the Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca (the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca) — APPO for short — that became a general assembly giving voice to the popular uprising.

As the weeks went on, the movement occupied government offices, shut down city streets and took over media outlets — radio and TV — and when those were sabotaged by the police, they took over others. Like the Zapatistas, women were active participants and leaders. In one now-fabled event, the women came out into the street banging on pots and pans and led a march that ended spontaneously in the takeover of a popular radio station. “Megamarches” filled the city’s main thoroughfares, drawing crowds of 800,000. The occupations and plantones, or sit-ins, were besieged by government forces, both uniformed and unmarked. Tear gas, water cannon and live fire were used against the protestors, themselves armed with rocks, slingshots and molotov cocktails. Barricades were assembled from abandoned cars, discarded appliances and furniture — anything that could block the bullets. Helicopters hovered over the city.

Ruiz Ortiz, the corrupt governor, did not step down as the protestors demanded. Leaders met in Mexico City to negotiate a deal between APPO and the state government but the members of APPO did not accept the terms of the agreement and the protests continued. After the murder of American Indymedia journalist Brad Will, then-president Vincente Fox sent in the federal police and police violence turned even more brutal. In the seven months since the protests began, at least seventeen people were killed by state, federal and plainclothes police.

Hired assassins murdered more. Scores were arrested on falsified charges. Hundreds were detained without charges, beaten, tortured and raped in police custody. Many have disappeared, or as they say, “have been disappeared.”

Photograph by Joanna Steinhardt

I’m in my fourth week in Oaxaca and it’s all of the things described here, and much much more. I’m struck by the complexity of this city, and humbled by what I don’t understand beneath the veneer. Oaxacans are not homogeneous…some are middle class and professional, others are visual artists, writers, foodies, musicians, and textile geniuses. Many are poor, yes, but their inherent dignity and friendliness shines through too. The USA has much to learn about this place. Are we listening? Can we help?