We were in their way. “Excuse me,” interjected the most assertive of the women. She looked anxious. Embarrassed, I let her by. Two Israeli men, deep in conversation, about money, had inadvertently blocked a group of young hijab-wearing Muslims from London’s Green Park tube station. I wanted to say something to my friend, but he beat me to it.

“You know in France, there are so many of them, they have to pray in the street.” “Bemet?”(Really?) I replied, feigning ignorance. “Yes,” he answered, narrowing his eyes. “The Arab population is exploding. The demand for mosques is exceeding what’s available.” Given how anxious Israelis can be about the

Given how anxious Israelis can be about the demographic threat of Muslims eventually outnumbering Jews in Israel, I assumed he was projecting.

“France is not Israel,” I told him, trying to downplay his concern. “There will always be more goyim than Muslims.” “Don’t be so sure,” Yair responded, looking at me as though I’d spent too much time in San Francisco. “It’s only a matter of time. I don’t know if you’ve ever been in Paris on a Friday afternoon, but if you’re in the wrong neighborhood, seeing hundreds of Muslims praying can be frightening.”

Watching an Arab roll out a small rug on the sidewalk last week, and get down on his knees, I was taken aback. Not because I was intimidated by what I saw. This was one person, not one hundred. It was his location. This was northern Italy, not Paris. Turin, to be precise, on a busy street in the middle of the city, less than a block from a church. It was an intensely public display of piety. The contrast was stunning.

Making a point of walking around him, I thought back to my conversation with Yair. “Have you ever heard really loud church bells?” I imagined asking him. “Have you ever heard them week in and week out?” I was thinking of the sounds of the Lutheran church two blocks away from our studio apartment, in Stuttgart. Every Sunday, we’d be woken by their loud, repetitive clanging. There was no escape. The sound of the bells would fill every inch of our home. What was the difference?

I wish I could convey how alien I found those sounds. As hard as I tried to make light of their annoyance by comparing them to 80s industrial music (“It reminds me of Test Department,” I joked to my sleepy wife,) these sectarian noises left even less room for our religious difference as, I would imagine, masses of kneeling French Muslims did for my Israeli friend. If only he didn’t have the Arab-Israeli conflict to help frame everything. I take that back. If only he didn’t have it frame everything for him so fearfully.

I’m not exactly in a position to offer an alternative. It is precisely because of the conflict that I’m so preoccupied with living in proximity to non-Jews. It’s why I imbue our interactions with so much significance. It comes with the territory, in much the same way that rightist Jews can’t stop thinking about Nazis and Europe whenever they talk about the Palestinians. Still, I’d rather be in the position of worrying about being understanding than forever trapped in my own Warsaw Ghetto. It’s a lot more manageable. You can compartmentalize the trauma, and still do other things with your life.

Frequent drives through nearby Switzerland, within view of anti-immigration posters by the Swiss People’s Party (SVP), have afforded me a degree of relief. Even in Israel, one would be hard-pressed to see billboards as openly racist as these. Their nostalgic, fascist-looking emphasis on sinister icons such as missile-like minarets and burqas allows me to feel a rare moment of maturity. As self-congratulatory as it sounds, it’s not. It is inseparable from an intense disappointment in Europeans, for being no better – or worse – than us. Our worst are from Europe, after all. Not all of them. Certainly the most iconographic ones.

Working on an article for The Forward several weeks ago, I invoked the example of my parents living in between an Arab village, and Israel’s current Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. Retelling the story of how, on Jennifer’s first trip to my parents’ new home (they had just moved in) upon hearing the sounds of Jisr‘s muezzins broadcast their midday call to prayer, she expressed astonishment that Netanyahu lives next door. “Bibi hears the same thing in Jerusalem. He’s used to it,” I quoted a rightwing family friend present, in response.

Indeed, as horribly reactionary on racial issues as Israel’s present Prime Minister is, like most Israelis, Netanyahu is also forced to make certain concessions, on a daily basis, in order to survive. In Israel, that is, one of the least appreciated multicultural states. Not just in terms of its conflicting Jewish and Muslim populations, but also amongst Jews themselves, hailing as they do from as disparate locations as Chisinau and Zurich on the one hand, Addis Ababa and the Atlas mountains on the other.

The first time we heard the bells, Jennifer compared them to the sounds of the muezzins inside my parent’s home. “They’re all-encompassing, enveloping even,” she said sounding exasperated, as though to emphasize how overwhelming the noise always is. “You can hear them throughout their house.” “Yeah,” I remember chuckling, as I stood in the kitchen preparing breakfast. “It never ceases to amaze me how little actually separates Europe from the Middle East.”

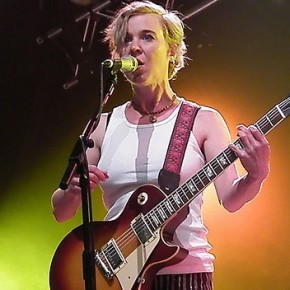

Photograph courtesy of Joel Schalit

I found this to be a very nice article. Very human and giving a piece of insight into the similiarities between countries and cultures.

Great article Joel. It has the right mixture of everything for me: personal, journalistic/observational, interactive, historical…a journalistic memoir. Thank you.

Thanks for the kind words, Johannes and Phern. Totally appreciated!