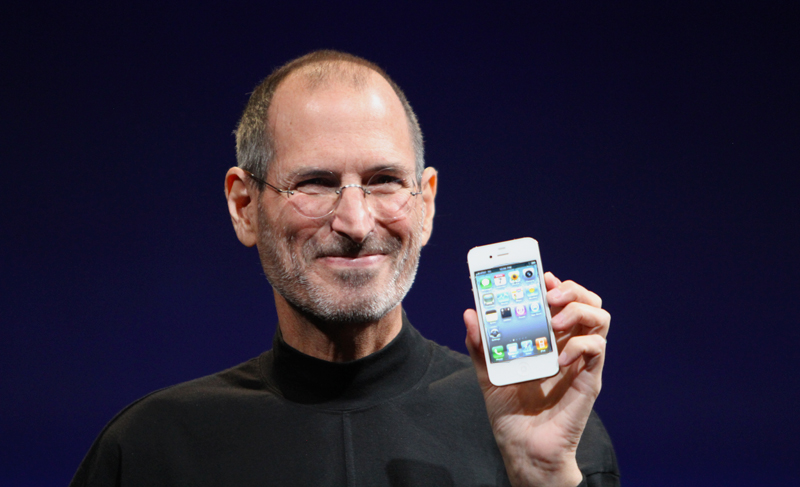

As word of Steve Jobs’ death spread, it was apparent that he had entered the pantheon of the Think Different campaign he promoted upon his return to Apple Computer in the late 1990s. Unlike the vast majority of corporate executives, he had become a celebrity that millions of people recognized on sight, someone who had transcended the need for a caption. But as tributes began to saturate social media, it also became clear how hard he was to size up.

Reading what my own friends and acquaintances posted to Facebook, Twitter and their personal blogs, I was struck by how many of them wanted to hold Jobs up as a particular kind of role model. Certainly, Jobs was a brilliant pitchman for his company’s products and a manager with a legendary – and often maddening – attention to detail. Even as they acknowledged these qualities, though, folks in my social media network seemed more interested in the way he had lived his life. For every mention of what the Apple II, Macintosh, iPod or iPhone had meant, I saw five referencing his 2005 commencement address at Stanford University.

Part of the reason, surely, was that Jobs used the occasion to craft a concise autobiography in which he discussed both his unconventional education – he never finished college — and his struggle with cancer:

Death is very likely the single best invention of Life. It is Life’s change agent. It clears out the old to make way for the new. Right now the new is you, but someday not too long from now, you will gradually become the old and be cleared away. Sorry to be so dramatic, but it is quite true.

Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma — which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary.

Echoing Joseph Schumpeter’s concept of “creative destruction,” Jobs’ argument here provides the theory to his practice as a business leader. It’s surely no accident that Apple stepped up its product development under Jobs’ second tenure at the firm, regularly phasing out the not-very-old to make room for the new.

What’s most striking about this passage is the way it personifies nature. Life isn’t an impassive biological process, but a being that “invents” its own undoing. This formulation calls to mind the big-picture psychoanalysis of Sigmund Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle, which brilliantly teases out the relationship between death and desire.

We need to die in order to live. That’s an especially compelling message right now, as so many people confront the realization that they will probably need to start over from scratch. As Jobs notes elsewhere in the commencement address, that’s what he had to do when he was expelled from Apple, the company he had co-founded, back in the 1980s. To be sure, most people who lose their jobs cannot count on an influx of venture capital to get them back on their feet. But by publicly confessing how bad he felt after his dismissal, Jobs created a powerful locus for identification.

Not to mention that he turned death into the ultimate “killer app.” The language he uses to discuss it in this passage is almost identical to the language he used when showcasing new Apple products. Time and time again, Jobs would find a way to make customers realize that they desperately needed technology that they had never really countenanced before: “You might think that life is all you need. But I’m going to show you how it can be radically improved with the introduction of death.”

The paradox inherent in the lifestyle Apple has been pushing since the Apple II, but particularly since the iPod’s introduction in the fall of 2001, is that we’re supposed to see technological bondage as liberation. If that sounds overly dramatic, try hiding your friend’s iPhone for a day. The withdrawal symptoms will be eerily like the ones that accompany the cessation of drug use.

What Jobs was really selling at Apple was a way of extending personal identity into the realm of commodities that can’t die because they were never alive to begin with. The music, pictures and books you store on your computer, iPhone and iPad are indices of your selfhood that are theoretically invulnerable to the ravages of time. In a way, then, his death was the perfect product endorsement.

Oddly, of all the things written in the wake of Jobs’ death, perhaps the most apt was a tweet by a twenty-three-year-old American football player, Jacksonville Jaguars’ defensive tackle Nate Collins: “The craziest part of Steve Jobs dying I bet most people who found out about his death most likely was using a device he created.” We can debate whether it’s fair to say that Jobs should be given credit for technology he didn’t personally design. But there’s no doubt that his spirit, if you will, lives on in each and every one of the “insanely great” Apple products he promoted during his tenure.

Indeed, although it might seem disrespectful to make the analogy, Jobs’ relationship to goods like the iPod and iPhone was an awful lot like the one evil Lord Voldemort has with his horcruxes in the Harry Potter series. Just as Voldemort didn’t create the physical objects into which he parceled out his life force, Jobs didn’t personally fashion any of Apple’s hardware. But by insisting that they be as good as they could possibly be, so that he could pitch them with absolute sincerity, he added massive value to them. The products he personally demonstrated always did better than the ones Apple introduced without his public stamp of approval.

If, as Karl Marx argued, the labor of workers is congealed in the commodities they produce, what are we to make of this Jobs effect? Apple has received justifiable criticism for the conditions under which its Chinese workforce operates. Jobs clearly didn’t suffer in the way that the men and women assembling iPhones do. And yet, it’s clear that millions and millions of people have felt that there was something of his humanity congealed in Apple products as well.

Maybe that’s where Jobs’ genius manifested itself most fully. According to Marx’s account, the reason workers fetishize commodities is because they desire to figuratively buy back the labor that has been alienated from them. What Jobs managed to do, somehow, was get people to fetishize Apple products because they believed that he was inside them as well as the company’s workers.

This trick has raised the ire of many. Apple detractors have regularly lambasted the cultish devotion of their loyal customers. They argue that the company can overcharge for products as a consequence. And they have a point. So do the labor advocates who question why one of the world’s richest companies, which makes a big show of treating its white-collar American workers well, can permit its supply chain to include highly exploitative factories overseas. Predictably, as the initial waves of adulation subsided in the wake of Jobs’ death, these critics started to assert themselves in social media.

As satisfying as it might be to dismiss Jobs as just another overpaid, self-aggrandizing capitalist, however, the stereotypes being circulated in the Occupy Wall Street campaign don’t fit him very well. He may have been a perfectionist who was overly hard on underlings. He may have been oblivious to the suffering inflicted on the people building Apple products. But he was never the Old Boys’ Club sort of CEO, golfing his way to a bigger severance package.

In other words, though Jobs wasn’t ever a worker in the Marxist sense, he certainly worked his company’s products hard. Just as significantly, he always advocated that the idea of a particular piece of technology and the narratives into which it could be inserted were as important as the technology itself. That achievement alone would be enough to confirm his reputation as a masterful proponent of innovation. Combine it with his special gift for making consumers believe that they were buying him along with Apple products and you end up with a figure who should inspire all of us to “think different” about the nexus of labor, technology and identity.