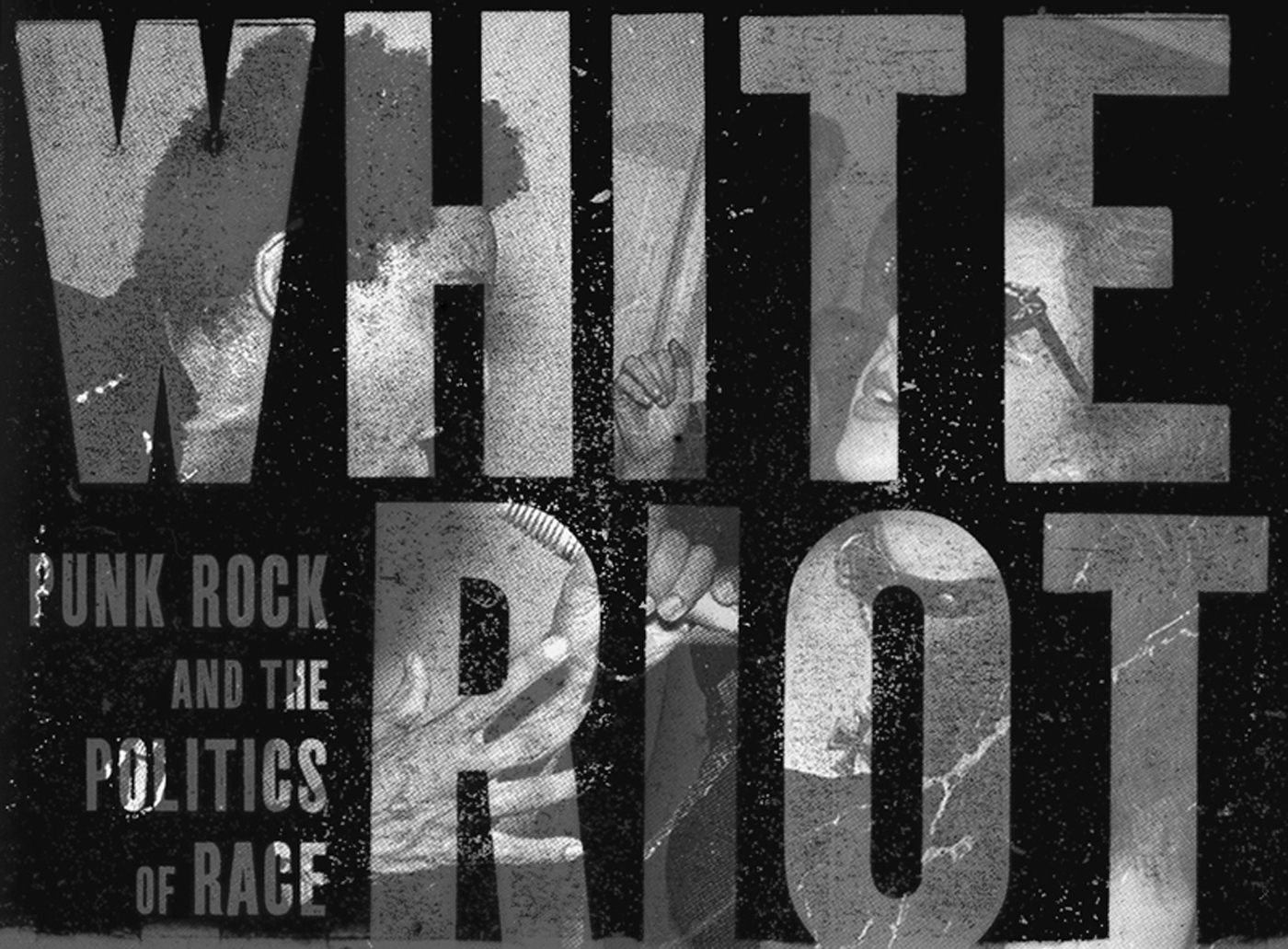

Given the recent glut of books about punk, it’s hard for a new one to stand out. But White Riot: Punk Rock and the Politics of Rage does so with ease. Co-editors Stephen Duncombe and Maxwell Tremblay have put together a provocative collection that strikes a delicate balance, equally compelling as a classroom text and a call to action. The pieces they include testify both to punk’s remarkable elasticity as a cultural form and the rigid reflexes that often limit its appeal.

White Riot confronts questions about racial identification that punks cannot afford to ignore. Duncombe and Tremblay understand that punk’s pretense to universalism will always be troubled by the whiteness, whether wished away or proudly declaimed, that has marked it from the beginning. By documenting the position of white power punks alongside the multicultural ethos of cultural progressives, they remind us that the punk makes it possible to articulate the relationship between identity and politics in vastly different ways.

As disturbing as some of the material in this collection is, however, its breadth ultimately demonstrates the power of punk to communicate a sense of belonging that goes beyond race without ever being free of race. Punk is a way of proclaiming that one has taken up a position outside of mainstream society, attractive both to suburban American youth unconscious of their racial privilege and minorities who want to take ownership of their otherness. What makes White Riot so politically valuable is that it enables us to make sense of this appeal without letting us forget the divisions that structure it.

In the interview that follows, Duncombe and Tremblay explain their goals for the project, while also reflecting on its connection to the wider world. Topics covered include Norman Mailer, the Noble Savage, unspoken racial privilege, self-identification, the Race Riot zines, Afro-punk, the rejection of whiteness, and White Power.

Charlie Bertsch: There’s a combination of breadth and accessibility to White Riot that would make it good to teach in a class. When you set out to put the book together, was one of your goals to make it educator-friendly?

Stephen Duncombe: Although we weren’t thinking of it as strictly for a classroom setting, we were definitely thinking that we didn’t want twelve academic essays with no introduction. What we really wanted to do is tell a story. Actually, because there was so much great material out there and because of the nature of that material, we wanted to let people tell a lot of the story themselves.

Maxwell Tremblay: It was more important that we try to make an argument by arranging pieces than by speaking for them.

SD: The thing about punk, as you know Charlie, is that punks love to talk about themselves. So there’s no shortage of great smart writing out there scattered in ephemeral fan zines that get twenty or thirty copies of them published and then disappear. So a lot of our work was hunting that stuff down, then finding the best academic articles — and there are some really good ones out there — and weaving it all together. We tried to give the book a texture that would be partially academic, partially classic rock journalism like Lester Bangs and Greil Marcus, and a lot of fanzine writers whom no one has ever heard of. We don’t even know the names of some of them.

MT: You see the diversity of people taking this topic seriously. It’s not just the four dirty, anarchist punk kids over in the squat over here. It’s cultural critics. It’s scholars.

SD: One of the funny things we noticed, though, is that the same critique gets made over and over. An argument that Lester Bangs makes in the 1970s about punk’s racism then gets made again twenty-five years later by a young, non-white punk from Toronto. That doesn’t make it less original. It means that punk still has to work out a lot of these racial issues.

CB: Just as every generation seems to produce punk bands, as the stereotype goes, who play the same three chords, the same thing happens with the critique. But that doesn’t mean that the critique is any less valid just because someone has done it before.

SD: Because it’s not about the critique; it’s about the conversation.

CB: The first section of White Riot includes material that predates punk, starting with Norman Mailer’s famous essay “White Negro.” This gives the book a different feel from writing about punk that treats it as a “year-zero” phenomenon, all about breaking with the past.

MT: Punk rock is very good about historicizing itself in certain ways. For instance, there’s a coffee table book listing every Danish punk band that came out between 1977 and 1984. But some things fall through the cracks, especially pre-punk things that informed the structure that punk rock ended up taking

SD: That’s why we start with Mailer’s essay and then James Baldwin’s response to the piece, because that sort of trope of finding your liberation in the Other, which is really necessary for understanding early punk rock, predates punk rock. It predates even the 1950s. It’s Rousseau’s Noble Savage; it’s all those folks finding their freedom, their non-whiteness in the Other.

CB: Another thing about your book is the way in which it contextualizes the White Power punk material, which gives the anthology a different quality than the ones where all the contributions are basically leading to the same point. It’s almost like an alien body in the middle of the book. How did you go about framing that material?

MT: The first part of the answer is, “Very carefully!” It’s not the sort of thing you can really do research on in public, unfortunately. I think it had to with taking the gesture seriously. And being very frank about confronting it. Not just saying, for instance, “Fuck White Power! Fuck Nazism!” but to look at what was so attractive to white supremacists about punk rock. And the thing about it is that they’re very transparent about what that is: it’s rebel music; it’s youth culture; it’s got this outsider sheen to it; it’s actually a very effective recruiting tool. They’re really very honest about that, more honest than most left punk bands would be.

SD: We also felt that it’s an essential part of understanding punk rock. When the Dead Kennedys sang, “Nazi Punks Fuck Off,” well, there are Nazi punks. We might like to think punks have always been on the Left, sticking it to the fascists. But who are the Nazi punks? They identified as punks.

This material is particularly important because the first part of our book is really about whiteness. It’s about the various strains of whiteness that get articulated through punk rock, from that inchoate “We’ve got to identify ourselves as white because we’re living in a multicultural society” to the Clash type of very comfortable radical whiteness, the sort that most of us would subscribe to. But the other way punk gets identified with is in conjunction with white supremacy. That comes out of the destabilization of whiteness. And when whiteness gets restabilized, that’s one of the directions it goes. It is as punk as left-wing punk rock. We really felt that you had to admit that.

Max and I talked about how, if you read some of that stuff in there and replace “Zionist occupation government” with “capitalist corporate record companies,” essentially it’s the same argument that’s being made. That’s not to say that there’s something right about what the fascists and the racists are saying. It’s just to say that they can mobilize the structure and the rage and the rhetoric of punk rock very easily.

MT: They have to work harder for it. Which shows you that there’s an anxious match-up between their taking up of that critique and the truth. That’s the case with the piece in the book about the guy trying to rewrite the history of rock and roll as a white phenomenon. You end up with very batshit developments as a result.

SD: It was an uncomfortable section to put together. And we’ve gotten some shit for it. But we think it’s an absolutely necessary section if you’re really going to be honest about the role that race has played in punk rock.

MT: On that tip, as an anecdote, we did an event here in New York at The Strand, a punk-rock listening party where we played songs from the book. We played a piece of “White Power” by Skrewdriver. And my friend tweeted at me the other day that that was the one song she walked away humming. So it really shows you why punk rock appeals to these folks. It does have that catchiness that gets in your head.

CB: Another thing that comes out of the book is people of color who, despite the fact that they regard punks as often being clueless about their racial privilege, still want to identify as punk. How did you go about articulating that idea of racial identification without reproducing the dynamics that people of color have so ably critiqued in publications like Maximum Rock and Roll?

SD: Luckily, we didn’t have to do it, because punks of color did that work for us in a number of ways. One thing we did do is showcase the history of non-white punks in punk that has always been there from the beginning. It ain’t hard to do, OK? You look at Bad Brains. Or you look at Black Flag. When they’re singing “White Minority,” the lead singer is Puerto Rican, the drummer is Latino, the producer is black. But somehow that gets written out of punk and we think of Henry Rollins, the Ãœber White Guy, as identified with Black Flag. So some of it was just resurrecting the real history of punk rock which, while the majority, demographically, is white, has hardcore contributions from punks of color from the get-go.

MT: It’s definitely a delicate little dance you have to do. I think it’s important to address the whiteness aspect, because really that is how punk understands itself, both rhetorically and demographically. I think in terms of editorial decisions it really was about getting the best writing that was out there, but also trying to let these identifications speak for themselves to the greatest extent that we possibly could.

SD: I think this really comes out in the introduction James Spooner wrote for us, which he ends by saying, “Am I black or am I punk? I’m both. Fuck you.” That’s this beautiful moment, which is to say, “I own punk. I am punk. I’m not an alien body. In fact, the body has to accept me as part of what it is.” That last section of the book is about what happens when the vibrant centers of punk go to Jakarta, Mexico City and Saõ Paulo, where the white-black, white-Asian, white-Latino nexus really doesn’t hold anymore.

In some ways, we see the most promise in those scenes insofar as it won’t be a white riot anymore, because whiteness isn’t necessarily a pertinent category. Yes, whiteness travels with punk, as punk goes international. But it gets diluted; it gets overturned; it gets appropriated; it gets applied in different ways and starts to mean different things. Punk as a popular cultural form has that wonderful elasticity, which will allow it to survive.

CB: I have friends living outside the United States, in places like Germany, Taiwan and Brazil, who tell me about all the interesting things going on with hip-hop there. That makes me think of the international scene reports in Maximum Rock and Roll, from places like Jakarta. When you think about that elasticity of punk, how it can so easily be transported to different cultural contexts and still work the way it’s supposed to work, historically, the same thing seems to apply to hip-hop.

SD: Here are these two musical forms which grow up about three miles from each other at the same time.

CB: With hip-hop, obviously, you have identification with an idea of blackness. The other day I was listening to Karkadan, an Italian hip-hop artist of North African ancestry. What he does is very informed by NWA on forward. But he’s from Tunisia and he lives in Milan. Just as whiteness — to use your formulation — gets diluted, overturned and appropriated when punk moves to Jakarta, something analogous happens to blackness when hip-hop moves to Milan. I’m curious how you see hip-hop and punk relating to each other on the global stage?

SD: There are two answers to this. The first is that I don’t know! But we should know and it would be a great future book. But the second is that I think you raise a really interesting question. How much of the spread of hip-hop has to do with the ideal of blackness and identifying with the black underclass as a representation? So you can live the thug life in Milan and transport yourself mentally into the Bronx or South Central Los Angeles. How much is that true of whiteness and, say, punk in Jakarta? That is, can you transport yourself into Orange County or Queens?

My hunch is that it is not working exactly the same way, that the Jakarta kids are not necessarily identifying with whiteness, that the Mexico City kids are not necessarily identifying with whiteness. What do you think, Max?

MT: I don’t know. It’s incredibly complicated. My inclination is to say that there’s not the same romanticizing of suburban punk kids, because there’s nothing particularly romantic in the popular imagination about that. The punk gesture is all about raging against that.

But where they are structurally similar is in finding a language of opposition, a language through which to articulate outsider-dom. I think one of the more interesting things, speaking of hip-hop, Europe and race, is not in the Mediterranean countries where you do have large immigrant populations, but in a country like Denmark, which is primarily white and where most of the hip-hop artists are white kids. How do you make sense of what hip-hop means in that context? It seems to be less about fetishizing the African-American experience and more about class in a very strange and interesting way.

CB: I want to talk a little bit more about the concept of identification, which has come up a good deal in our discussion. In film studies, there has been a pronounced shift away from theories of identification in some quarters, a sense that the concept can’t be liberated from a methodological approach that is outdated. There’s a concern that merely invoking “identification” forces us to interpret according to a psychoanalytic framework. But I’ve found that it’s very difficult to avoid using the term even when having casual conversations about culture. So my question is, what do you have in mind when you say “identifies with”? What are you trying to avoid when using the term? And what theoretical or political legacies are you trying to foreground?

MT: I think on some level we’re trying to keep two registers in play, both the common-sense meaning of the word, which is important because most of the people writing the pieces are not theoreticians themselves, and also that more technical expression, which is kind of unavoidable when you’re talking about music. Especially a music which is as saturated with political presuppositions as punk rock is. It’s really about a process of subjectification that can go various ways.

I’m sure there are some film theorists who would take me to task for this, but I think it’s a little easier to distance yourself from a cinematic narrative when you’re sitting in a movie theater or on your couch than it is to do that when you’re watching a band with seventy-five other sweaty people, pointing your finger and shouting along. It’s a very different, more subjectively involved process. I think one sees oneself in bands and in zines and in records more accessibly.

SD: I think how we were thinking about identification when putting this book together had a lot to do with how people were talking to us about identification. Identifying as a punk was a way for a lot of people to move away from other identities that they might otherwise have. And that was often very problematic. One of the tropes that the Race Riot folks brought up is that white punks would identify as punk, disown their whiteness, and thereby not recognize that the rest of the world was still identifying them as white and giving them certain privileges.

But one of the things we liked about punk as a popular musical form in which people could find their voice is that it was a way for them to navigate their own ethnic identities, asking not only what it means to be white, but also what it means to be black, Latino or Asian. And so it became, as a subjective identity, a way that one could navigate one’s so-called objective identity.

MT: And very much in a way where one doesn’t have to resort to quasi-transcendental sciences like psychoanalysis because, shit, they’ll tell you what the structure of their identity or their experience of identification is!

CB: Part of the reason that film studies leaned so heavily on psychoanalysis is that when you’re sitting in a darkened theater, you’re as close to being asleep as you’ll ever be when you’re awake. So there’s a physiological passivity in play there that makes folks think of stuff that you’re not in control of. Whereas with something like punk, you’re making a choice whether to get in the pit or not, which bands to pay close attention to, how you act between sets. It’s all about a very bold assertion of choice, self-identification.

That’s where I think music in general, but especially punk and hip-hop, hold out an alternative in terms of thinking about identification. Because the models typically used in cultural theory, partially thanks to that film-theoretical tradition, are more grounded in a sense of the subject’s passivity, in being identified as something by someone else and then feeling called to inhabit that identity. With punk, by contrast, the emphasis is on the subject taking action, choosing to identify differently.

Of course, there’s still the problem of how people identify you regardless of how you identify yourself. As you were saying earlier, Stephen, just because someone regards becoming a punk as a rejection of whiteness doesn’t mean that the world at large is going to stop classifying that person as white. Still, the emphasis on agency in punk is noteworthy. There’s a reason they call it do-it-yourself culture, after all. What we see, in a sense, is a belief in do-it-yourself identity.

MT: I think the agental moment is very important. But one thing that occurred to me just now is that there are complex networks of privilege informing that agency as well. Particularly when you think about black punks, for instance. “Punk” is something they are hailed as, a homophobic slur. And so I wouldn’t want to make it seem too hunky dory — “I can identify as punk and everything’s great!” — because “punk” is very a complicated term that people in various margins of racial outsiderness have to negotiate, especially when it does take on that poisonous valence.

SD: The thing is, a lot of punks of color will talk about the fact that as they slipped their given identity and took on the mantle of punk, they’d get crap from people asking, essentially, “What, are you trying to be white?” So punk is identified as white and therefore it becomes very complicated for them. Here’s this way that through their agency they can adopt a race-less identity — at least that’s the ideal — which is, “I’m punk,” yet it is seen both by people from their own ethnicity and, unfortunately, white punks as being white. And that gives them a lot of anxiety.

Now what James Spooner has done with Afro-punk and a lot of the folks in the Race Riot zine movement are doing now is to create, through their agency, a community of identity, so that they can actually look at someone else and say, “You’re a punk and you’re black,” or, “You’re a punk and you’re non-white.” That way it’s not just this individual agency and identification, it’s also this idea of a community generation. One of the things that’s really cool about Afro-punk is that Spooner went out in search of other black punks, because he felt so alienated and alone, and in that search he ended up creating his imagined community. So there’s an Afro-punk festival, an Afro-punk website and so on.

White Riot is available from Verso. Ask for it at your local independent bookstore.