Joy and rage, as each new generation bangs up against its own possibilities and the world as it is, are what gives rock music its energy and power. This is why first albums are rarely surpassed, why corporate pop is such a betrayal, and why listening to Sir Michael Philip Jagger failing to get satisfaction aged 65 is less authentic than it was in 1965.

More compelled than most adolescents to turn her frustrations into music was Kristin Hersh. Suffering from an unusual type of bipolar disorder, she hallucinated music being played around her, only finding relief when the music had coalesced into a workable song for her band, Throwing Muses. Thirty years since they formed, and twenty-five since her diagnosis, the Muses played a few dates on the American East Coast, and are just embarking on a new European tour.

In 1985, though, Hersh had plenty to revel in and rail against. Much of what we know comes from her surprisingly excellent 2010 autobiography Rat Girl. With a lot of material taken from her diary, it covers the time that Hersh discovered in short order that she was bipolar, pregnant and signed up to an appropriately respectful record company. Rat Girl achieves the tricky tasks of on the one hand explaining the substantive background of obscure lyrics, without spoiling their effect, and on the other, conveying the perspective of a slightly disturbed naïvete without the 2010 Hersh over-, or under-selling her younger self.

With enigmatic, stylized vocals over the top of a jangling, proficient rock band, Throwing Muses were one of the most unpredictable bands of alternative rock’s heyday, in the late 1980s. Hersh was the female lead whose elliptical, often snarled, lyrics were evocative when discernible, and added up to a tortured internal mythology whose pathos and anguish testified to her manic depression. For her English fans, they were The Smiths meet the Cocteau Twins meet One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Despite forming and developing in Providence, Rhode Island (before moving to Boston) Throwing Muses found more success in the British indie scene than in America. Signed by the groundbreaking London Indie label 4AD — who, until then, only signed British bands — the Muses went on to tour Britain and Europe throughout the 1990s behind a series of moderately successful albums : Hunkpapa in 1989, The Real Ramona in 1991, Red Heaven, in 1992, University in 1995 and Limbo, in 1996.

Quirkier than The Smiths — David Narcizo, the drummer, refused to play cymbals for their early years — the Throwing Muses often sounded like they were playing related songs in different genres. Their musical ability and familial intimacy allowed them to marry this innate strangeness with a strangely suitable style. Narcizo, Hersh, Tanya Donnelly (on vocals and guitar) and Leslie Langton (with excellent, meandering bass) had grown up together. By 1986, the music reflected a shared background and a profound love of each other’s angle on life.

Narcizo’s drumming beat out a signature insistent rockabilly tattoo that drove songs on through different lineups as well as improbable chord and tempo changes. Donnelly, Hersh’s step-sister, who left the band in 1991 to work more with The Breeders and later her own band, Belly, added occasional pop vocal harmonies whose sheer incongruity led to an uncanny aesthetic. This process was matched by moments like Hersh’s spine-chilling rendering of a bewilderingly mundane line like the one from “Vicky’s Box,” on their eponymous 1986 debut album — “A kitchen is a place where you prepare and clean up.”

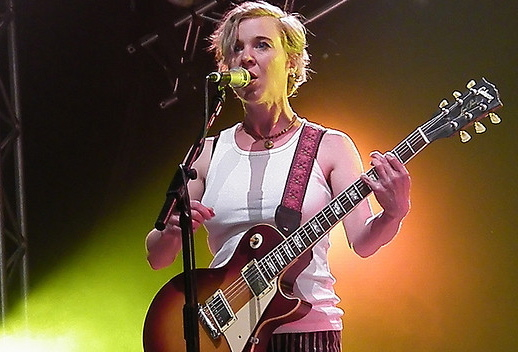

The changes in direction in the middle of a song, along with Hersh’s delivery as a woman possessed, made Throwing Muses music distinctive and strangely off-kilter. Listening to them was like visiting a dream version of the real world. And, in concert, it was even more so. In 1991, Hersh sang around the microphone with a hypnotized stare and a figure-8 swaying of the head, seemingly transfixed by her own music. From the opening breakers of Narcizo’s drum wave, Hersh gave the sense of having only a tenuous connection to the world in front of her material senses.

The lyrics from “Walking in the Dark,” from the 1988 album House Tornado are typical of Hersh’s output. As with the best art, they depend upon context. As with the best rock songs, they don’t come alive without their performance.

“I can’t forgive a dream /You own a question /It’s a body

You can make me cry / You have a right

I can see you live / I can’t forget you die”

A poignant opening gathers pace from a hauntingly slow start, accompanied, unusually, by a piano. It proceeds through a stop-start story (“My ghost of seasons past asked this bedroom what to say / I said stay I have to sleep tangled in my family’s hair”) until the song ends, inconclusively, having taken listeners on a journey to an indeterminate destination and expressed an inchoate gestalt.

In this way the first four albums are minor masterpieces. But the gem in the diadem is the bleak “Hate My Way.”

“So I sit up late in the morning and ask myself again

How do they kill children?

And why do I wanna die?

They can no longer move

I can no longer be still

I hate my way.”

With reflective intensity Hersh charts a specific and alienated world whose inner landscape is gothic. Her expressive ability and the sympathetic musicianship of her bandmates redeem her suicidal despair. The song takes the banal and, like Edvard Munch’s Frieze of Life, weaves desolation into a personal lifeline.

A three piece since 1993, Throwing Muses have only been sporadically as excellent. This is not to blame Hersh, Narcizo or bassist Bernard Georges. Watching Hersh at a Throwing Muses concert in 2011, she seems to have her stuff together. Hersh appears controlled and content, but still able to perform her distillations of youthful anger and confusion with panache and authenticity. There’s still a mild head rolling. The beat is there, but the compulsion isn’t. She seems, as far as this audience member can tell, to have come to terms with her way, to have achieved some degree of satisfaction.

The aging of the Rolling Stones is a phenomenon in its own right, and one charted in another surprisingly excellent rock autobiography from last year. From someone who has had to suffer the “unbearable” Sir Michael Jagger for a whole career, Life by Keith Richards is a fascinating insight into his life with the Stones. With the writing help of journalist James Fox and the brand recognition of the Stones, Richards received plenty of coverage, while Rat Girl, written by Hersh herself, had to rely on its own excellence and the support of her longtime core following for coverage. Both Richards and Hersh seem more content now than ever, less manic, less depressed. Who would begrudge them that, even if their music suffers?

Recommended Links

Excerpt from Rat Girl

Interview at KEXP in Seattle:

Review of NY gig

Home is Where the Heart Lies, Lifemusicblog

Electrify Your Head, A Pessimist is Never Disappointed

Closing Time, Boston Phoenix

Photograph courtesy of jaswooduk. Published under a Creative Commons license.

I’ve just added Throwing Muses to my Pandora lineup. I was listening to the Stones in 83, totally missed the ‘Muses. Thanks Dan Friedman.