Old paradigms die hard. It has taken a long time for the front offices of major league baseball teams to adjust to the new way of thinking, just as it has taken many fans of the game a long time to accept that things aren’t like they were back in the good old days. For reasons I don’t quite understand, this often comes out as a binary argument of aesthetics versus numbers. Old-school fans think the new “statheads” have no feel for the romance of the game. The new guys think the old school is peopled with fossils.

Much of this is behind the recent Hollywood hit Moneyball. The film, like the book on which it is based, gets many things right. But its portrait of the old school is harsh in unrealistic ways, falling victim to the stereotypes of the most extreme thinkers of the new paradigm. In fact, success comes in part from a useful blending of all sides, with old school and new bringing their particular talents to the table. Conflict makes for a better movie, though. When Brad Pitt is playing the exemplar of the new way, the old guys don’t stand a chance.

Quite a few of my friends looked forward to my take on Moneyball, because they knew I had a long obsession with the topics the film addresses. More than that, I think people assume I will take a particular stance, less romantic, more concrete, because of my place on the new side of the paradigm shift. It’s not just about baseball, of course. It’s why I am the right person to teach a critical thinking class.

Which doesn’t mean I lack for romance (the aesthetic/statistic split being silly in any event.) Nor does it mean I am an atheist about these things. As a friend said to me recently as we drove to the Winchester Mystery House, “you’re the scientist of the group.” I know less science than most people. But I am a believer, in the scientific method if nothing else. I believe in an analytic approach.

I hope to write a series of pieces that examine the way data impacts our lives. I won’t be able to do this without reference to my background in baseball analysis. The primary point is always that it’s not just about baseball; it’s about a way to see the world. I can’t tell that story without a digression.

Religion, Sisyphus and Me

My relationship to religion and spiritual matters wasn’t particularly unusual for a suburban kid growing up in the 1950s and 1960s. My father was a Catholic, my mom was some kind of Southern protestant. They split the difference and raised their kids in the Episcopal church. I was an altar boy, sang in the choir, even briefly served as the church organist (I sucked at the latter). My mom’s best friend was the minister at our church. We attended every Sunday.

In the later 1960s, as I became a teenager and the hippie movement emerged some fifty miles from my hometown, my spiritualism took a different form. I still went to church, but I also started taking drugs, first marijuana, then all the varieties of psychedelics I could get my hands on. My psychedelic experiences weren’t particularly spiritual in and of themselves. In what I saw at the time to be an amiable battle between the Timothy Leary version of LSD, where you created a special environment to maximize your communion with The One, and the Merry Pranksters version, where you dropped acid and went out in the world to play, I followed the latter. Still, during that time, I developed a connection with the crashing ocean waves at the local beaches that has never left me. I was always enthralled by the feeling of Oneness with the universe that accompanied the psychic breakdown of my brain chemistry under the drugs.

In short, I paid attention to the cosmic nature of things, threw the I Ching and pretended to know all about Jung’s theory of synchronicity. I assumed that everything in the world was connected, not just in the obvious ways (the rich exploit the poor) but in more mystical ways (when I move my hand, it disrupts the air, which is eventually felt by a passing butterfly, and onwards into infinity).

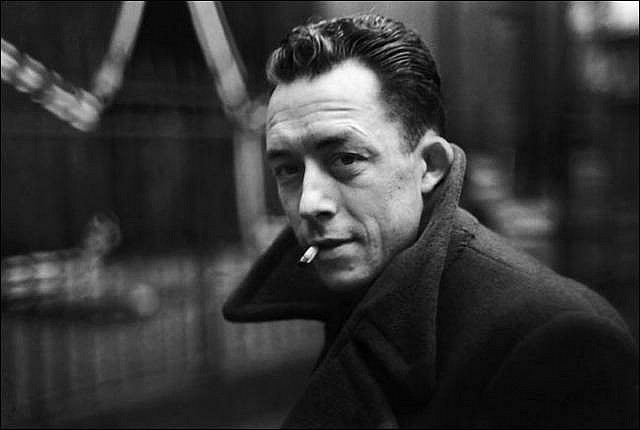

Meanwhile, when I was still a kid living at home, my mother and I spent many long nights talking about philosophy. Her minister friend encouraged her to read Christian existentialists like Paul Tillich. Somehow, I ended up reading many of those books, which sat on the shelf at our house. None made as big of an impression on me, though, as Albert Camus’ The Stranger. I was fascinated by the main character, Meursault, which actually wasn’t that odd at the time; there was something that appealed to the adolescent in me, I suppose.

In the early 1970s, I spent a year living in Indiana, and I returned there for several weeks during Xmas season in 1972. My friends and I would stay up until all hours, drinking wine and smoking weed, going on “adventures” like a trip to the supermarket to count the number of items containing garlic. By that point, my Camus readings had progressed beyond The Stranger. I read The Plague, although it had yet to take its spot as my favorite book of all time. And I read The Myth of Sisyphus, which led to a moment that remains imprinted on my psyche, nearly forty years later.

We were sitting around … probably high on some combination of things, although I don’t remember what, and I’m pretty sure it’s irrelevant to the story. I started talking about Camus’ Sisyphus, how he was condemned by the gods to push a rock up a mountain. When he got to the top, the rock rolled back down the mountain, followed by Sisyphus, who, when he reached the bottom, would once again push the rock up the mountain. This punishment was eternal. Sisyphus would perform his task forever, and would know as he performed it that he would be pushing that rock into eternity.

Something about the telling of that story got to me. I had a flash of insight, perhaps the only one I have ever experienced. I didn’t understand Camus intellectually. Rather, I connected in some visceral way, similar to how I felt at one with ocean waves when I was tripping. In that instant, I thought I understood the meaning of life in a deeper way than I ever had, before or since. We are all Sisyphus … this is the message that filled me with emotion far more than it filled me with an intelligent recognition of the facts.

I started to laugh.

I was always prone to giggle fits in those days (I’m still susceptible; perhaps we all are.) But this was not that; I was not giggling. No, I was laughing with awe and sadness at the wonderful absurdity of human life. We push the rock up the mountain, it rolls back down, we push it back up, indefinitely.

I am very suspicious when people say something changed their life. It seems to me that life-change is a process, that if we change at all, it takes a lot more than a moment, that it must be spurred on by more than just one event. And, in any case, I have no idea what was actually occurring as I rolled on the floor in uncontrollable laughter. But I do know that to this day, I think of my life in terms of what happened before that night, and what has happened since.

Of course, at the time, I wasn’t really thinking about what would happen down the road, or what the implications were for my laughter. But something happened that night, and whether I knew it then or not, part of that something was my spiritualism flying out the door.

Postscript

While I can’t pin down the exact moment when I crossed the line from starry-eyed cosmic traveler to the lover of the concrete that I am today, I do have one theory. I asked my wife, “When did I quit being a bit mystical about the cosmos, and start being more insistent on the value of rational thought?” “Well,” she said, “I don’t suppose we can put an exact date on it … by the time you were thirty, though.”

I turned thirty in 1983.

I read my first Bill James book in 1982. Bill James is the person who brought modern statistical analysis to the baseball world. There were people before him, there have been people after him, but he’s the George Washington of the group.

Perhaps I’ve discovered the roots of my own conversion narrative.

But it was also around that time that we got our first home computer, which means we’re approaching thirty years with at least one computer in our house. Baseball supplies the statistics; analysts like James ask the questions; but computers make the process of analyzing much easier. The computer is a tool, just as statistics are only data. If you don’t have a question that needs to be answered, tools and data won’t be worth much.

Still, the rise of the new paradigm in baseball occurred pretty much simultaneously with the rise of personal computing. And the ways statistical analysts look at baseball often reflect the way computers help us look at the world as a whole. Whether this new way of seeing the world is a good thing, I will leave for subsequent articles.

Photograph courtesy of Mitmensch0812. Published under a Creative Commons license.