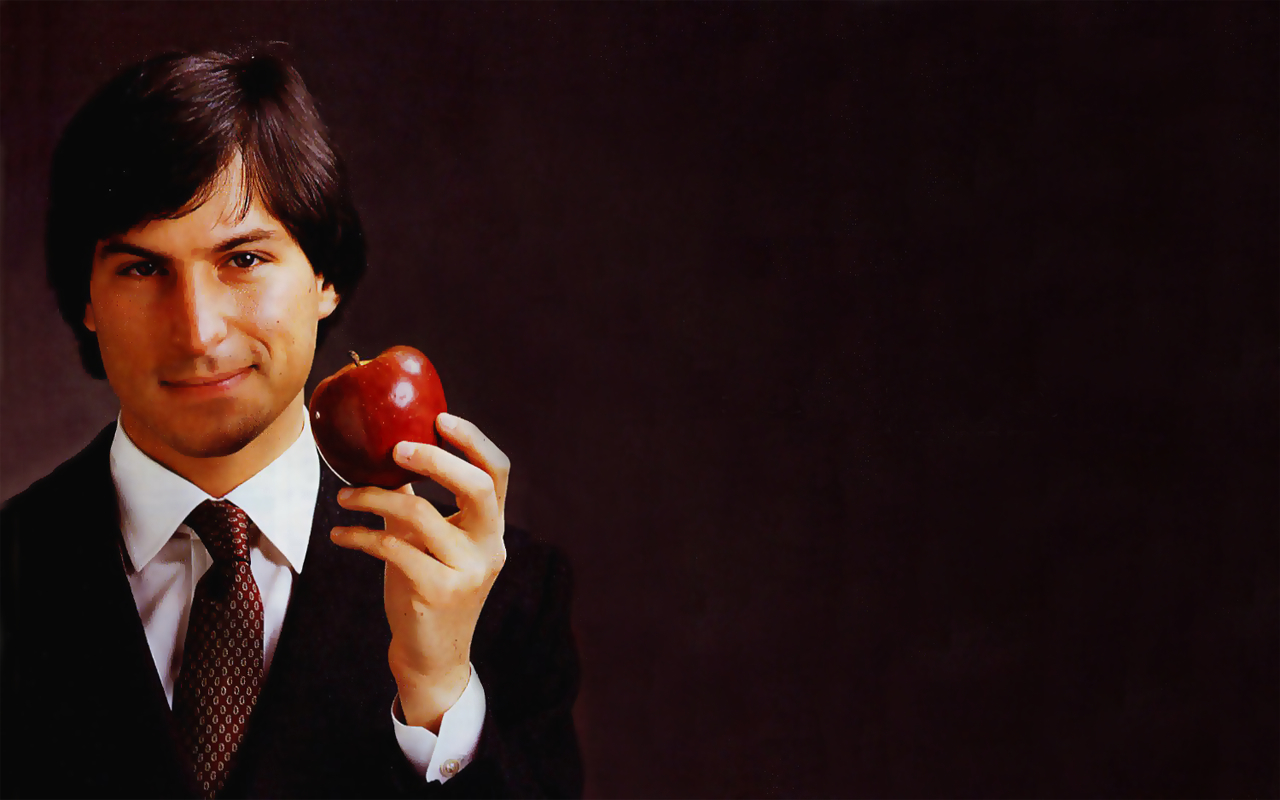

Steve Jobs should have been a rock star. So tremendous was the outpouring of public grief, you’d be forgiven for not knowing that he was a marketing czar. Though the fanboys and cult of Mac kids did their expected thing, it was the grief repeatedly expressed by laypeople that was so astounding, with mourners going so far as to stage homages at Apple stores. Granted, every media outlet was observing his passing. One could not help but feel programmed to react to it this way.

Despite all of this, little has been said about the man’s impact on the global business and design communities over the course of his career. Spanning over three decades, Steve Jobs had an equally significant impact on his colleagues, transforming both the way they did business, and, perhaps most obviously, the ways in which they created their products.

Part of it was his timing. As Walter Isaacson’s newly-published biography explains, Jobs grew up at the crossroads of the northern California high technology boom, and the 1960s counterculture. It’s essential to appreciate the synergy here, and how Jobs was able to wed the two, while selling personal computing, as an alternative lifestyle, in the process.

Prior to Apple’s founding, computing was viewed as the “evil system,” disrespected, if not despised by the decidedly luddite-leaning hippie counterculture. Though technology had its hipster champions (I.E., Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth catalogue) Jobs changed this by co-opting the emerging hacker, cyberpunk ethos, and grafting it onto the emerging consumer technology market. The best-known example is the critically-acclaimed 1984 Macintosh ad, pitting Apple (as hero) against IBM, later Microsoft, as evil (Big Brother.)

Such advertisements were not only crucial in selling Apple as an outsider brand for the emerging creative classes. They were an equally significant demonstrations of Jobs’ understanding of the importance of spin for sales. During the time of Apple’s second coming, marked by his 1997 return to the company, Steve Jobs was able to monetize the perennial appeal of great craftsmanship. Neither a developer nor designer, he had an intuitive understanding of engineering, and extremely refined aesthetic sensibilities.

One successful product hit after another, beginning with the iMac, followed by the iPod, the iPhone culminating in the iPad. With all of these astounding coups, Jobs could singlehandedly claim to be enriching peoples lives with well-constructed, obsessively detailed and beautifully designed breakthrough products, disrupting not one or two, but several industries in the process. Genius? Perhaps. Extremely bright, visionary, in the right place, at the right time, with a burning passion for perfectionism? No argument.

Less appreciated outside of professional circles are the precedents Jobs’ personal behavior set for his peers. Precedents which, by no means alien to other industries, sent enormously influential ripples throughout the business and design communities.

For example, how many times over the past decade have designers been subject to clients and senior management who so ignorantly claim, “We want to be the Apple of X industry”? The problem is not so much in the desire to create “insanely great products” as it is in facilitating a realistic process, and the ability to actually execute. As we know, saying and doing are two extremely different endeavors.

The most significant cultural element that propelled Apple, fueled by Steve Jobs himself, was an obsessive focus on detail, to design, inside and out. Not only the industrial design, but in the realm of human-computer interaction. It’s what designers refer to as “user experience,” wherein as much emphasis is placed upon a product’s usability, in its design, as its utility, and appearance.

According to Walter Isaacson’s biography, Jobs even went so far as to inspect Macintosh circuit boards and requested production lines be tighter, though most consumers would never see this. Similarly, Jobs ordered the manufacturing plant walls in Apple’s Fremont plant, to be painted museum white, and the equipment painted in bright hues to align with the then, multicolored Apple logo. One can appreciate the circuit board supervision. However, the latter point, about the factory might be more akin to the insane part of “insanely great.”

From the start, Apple chose to integrate its own hardware and software to control the user experience, in its entirety, even when many were critical of this move, arguing that Apple should in fact license its operating system to other hardware manufacturers. Had that happened, Microsoft’s standing in the OS market would, with good reason, look very different. However, Apple would have been relinquishing control of their OS, exactly because it is dependent upon Apple hardware. At this stage, we know who won this battle.

It was this obsession to design that, while insane at times, also proved to be the proper path in the end, for Apple, as a business, as well as for consumers. In these times, it’s hard to imagine a multinational firm bending over backwards and disregarding profits (at least for some time) to perfect product design. Some firms come to mind, but they tend to already have a solid footing in design, and high levels of customer satisfaction.

In the design community, we have a lot to be grateful for, with regards to Apple and Steve Jobs himself. Many of us wouldn’t be practicing any form of design, let alone interaction design, without the advent of the first Macintosh, and the increasingly refined and revolutionary products which followed.

And so I am conflicted about Steve Jobs’ legacy. As is widely known in technology circles, and well-documented in Isaacson’s biography, Jobs was an unbelievably difficult guy. Frequently derided as an asshole, the Apple founder wasn’t just considered overly demanding, but pathologically destructive. Jobs’ behavior was in fact so hurtful to his associates and employees, it was dubbed “management by character assassination” according to Isaacson.

For someone who considered himself ‘enlightened’, who encouraged non-conformity, and who studied Zen Buddhism throughout his life, there is no excuse to treat anyone poorly, be they colleagues or employees. The disjuncture is especially disheartening, as the obvious hypocrisy makes a mockery of the ideals so important to Jobs’ 1960s branding, in addition to undermining the cultural values consumers associate with his products.

Steve Jobs’ mean-spirited behavior, especially in relation to design management, similarly gave license to far less talented and visionary designers to behave as they pleased. Having experienced this firsthand at a number of firms, I can confirm that there is no lack of assholes in the design industry, or in business at large. It is my fear that in response to Jobs’ passing, we will somehow give a free pass to those who invoke similar privilege, as though it is a worthwhile exchange for the products they bring to our tables.

As much as I appreciate what Steve Jobs did, as a designer, whose focus is on user experience, I’m not sure the tradeoff is worth it. Imagine what kind of products Jobs would have created if he’d been more disciplined. Imagine what kinds of things we’d all create if we had design leaders who showed as much empathy as aesthetic sensibility. Not just towards consumers, but teammates and employees. That’s the part of Think Different I bought into. I’d like to think that’s what Steve Jobs ideally had in mind, too.

Poor interpersonal skills are quite common with genius visionaries. Looking at Jon Ivy’s eulogy of Jobs one can see what a timid, gentle personality he has, almost defusing (I’d imagine) Jobs’s mean-spirited approach. No surprise then that Steve had much regard for Ivy. It’s still not a healthy environment to work in, in my view. I find it sad.

And yes it’s rare to have individuals go so far in life, like Jobs, but even more rare are great teams. Where there are collective excellence and greatness. That’s almost unseen. Collectively, one achieve much more than on an individual basis. However it’s also a case of time and place when it comes to building a great teams.

I enjoyed this one.

Well written, Jen.

Thanks so much for your comments, Carl and Andrea. I appreciate them.

I agree with you, Andrea. The problem, in my view, is how this behavior is frequently mimic’d by less mature persons in the creative industries, who think that because they carry a certain degree of authority, they can exploit it without restraint, or concern, about the consequences of their actions.

The question then becomes how can we set positive examples for such persons, so that they can equate inspiration and success with responsible, stable management?

Power corrupts. Haven’t we learned this a thousand times in the history of humankind? I think you nailed it, Jennifer. Your depiction of Jobs reminds me of some of the sentiment that is coming out of the OWS movement: there is no individual or single company that can take credit for their own success. The infrstructure of the society we have all built, the taxes we pay, the roads we build, the hands we lend, all contribute to success. Some people cannot share that collective responsibility and need to take all credit themselves. Then they feel superior to everyone else. Then they feel entitled to insist that everyone submit to their will.

Well put. But don’t you think that, even with a skeptical eye, taking yet another look at the Cult of Steve is drinking the kool-aid? It just feels to me like hyper-individualistic narcissism is also part of the California spirituality and elite consumerism that Jobs masterfully hybridized. To riff on one of the above comments, great teams are not so rare, rather they are just rarely seen or acknowledged in the highly abstract ethos of the design obsessed. Jobs was a brilliant architect, but from Wozniak, to SPARC, to suiciding Chinese workers, there are all sorts of people who actually built the houses he sold. I’d like to know more about that than understand to which decimal point the Jobs asshole to visionary index can be parsed.