When The Coming Insurrection was first made public, it read to me like wishful thinking. Although rooted in Europe’s struggle to cope with the realities of multiculturalism, the uprisings that inspired the book seemed uniquely French. How could they be the model for an international movement?

Even if the depressing conditions that motivated young people in the banlieues to lash out were mirrored in other developed countries, only France had the rich history of protest required to mobilize frustration into political action.

Or so I told myself when I first encountered the text. Years of reading radical leftist theory had me wary of the tendency to exaggerate the scope of political crises, seeing in each threat to the status quo — a cluster of strikes, a spate of riots — the conditions for revolution. And my experiences as an undergraduate at the University of California in Berkeley, during which I spent a great deal of time hanging out with activists, had taught me to understand this hyperbole as a rhetorical strategy, a way to bolster the confidence of those participating in an action and to encourage those interested in joining it to perceive safety in numbers.

There was also the book’s Frenchness to consider. As much as I had once thrilled to discover the work of thinkers like Jacques Derrida, Jean Baudrillard and Guy Debord, part of me always felt like they were getting away with something. Instead of qualifying each assertion, as my academic training had taught me to do, they made bold claims unfettered by second-guessing. Indeed, even when they were urging caution, they did so with a confidence few American scholars could muster.

To my mind, The Coming Insurrection’s opening sentences, declaring that “the present offers no way out” and “everyone agrees that things can only get worse” seemed a perfect example of both leftist hyperbole and French recklessness. “Everyone” is a pretty big category, after all. And declarations don’t get more absolute than “things can only get worse.” No matter how tempting this dystopian worldview was to someone like me, beset by personal and professional misfortunes, my inner skeptic was fully engaged by the end of the first paragraph. I knew I would be reading the rest of the book through a filter, mentally adding the qualifications that the book’s authors had so strenuously eschewed.

Consuming the book in this way drew my attention to those moments when The Coming Insurrection’s anonymous authors, the so-called “Invisible Committee,” are trying hard to connect the uprisings in the banlieues that swept France in the fall of 2005 with other instances of political unrest. If the book’s assessment of the present state of world affairs represents a negative form of wishful thinking — presuming that things are worse than they really are — one that is particularly common on the Left, then making connections in this way is its flip side.

To perceive affinities among the participants in actions that outwardly seem to have little in common is the most important intellectual work performed in this kind of radical theory. Indeed, it sometimes seems as if the exaggerations of the former type are just a foil for those of the latter, a way to produce solidarity by proleptically demonstrating its existence. One obvious example of this rhetorical strategy comes at the end of The Coming Insurrection’s fourth chapter (or “Fourth Circle”):

Every network has its weak points, the nodes that must be undone in order to interrupt circulation, to unwind the web. The last great European electrical blackout proved it: a single incident with a high-voltage wire and a good part of the continent was plunged into darkness. In order for something to rise up in the midst of the metropolis and open up other possibilities, the first act must be to interrupt its perpetuum mobile. That is what the Thai rebels understood when they knocked out electrical stations. That is what the French anti-CPE protestors understood in 2006 when they shut down the universities with a view toward shutting down the entire economy. That is what the American longshoremen understood when they struck in October 2002 in support of three hundred jobs, blocking the main ports on the West Coast for ten days. The American economy is so dependent on goods coming from Asia that the cost of the blockade was over a billion dollars per day. With ten thousand people, the largest economic power in the world can be brought to its knees.

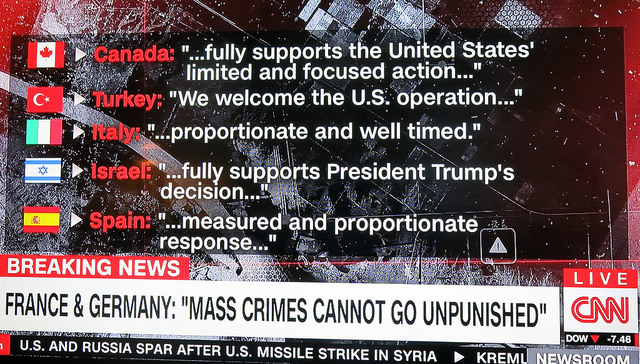

It’s unlikely that the Thai rebels were giving thought to French university students or that French university students were modeling their protest on a strike by American longshoremen. But by articulating a relationship between these isolated events, suggesting that they shared an understanding of how to find “weak points,” the authors are constructing a narrative in which these acts of resistance can all be regarded as components of an international movement. Moreover, this narrative — one, it is important to mention, that is produced after the fact, in retrospect — invites readers to make their own contributions going forward, discerning other examples that can be used to reinforce the basic argument.

That’s clearly what alarmed the French government, which responded to The Coming Insurrection’s 2007 publication with a vigorous attempt to identify its authors, culminating in the arrest on November 11th, 2008 of nine individuals (a tenth would join the group later) charged with a plan to sabotage overhead electrical lines on the French railway system. Although there was little hard evidence, either that they were involved in this scheme or had helped to write the book, the conviction of the country’s anti-terrorism experts that theory and practice were so closely intertwined signaled a major shift in the attitude towards the work of leftist intellectuals. Instead of being regarded as harmless relics from the Cold War era, nostalgically revisiting concepts that are no longer relevant, the authors of the book were treated as highly dangerous. Not since the end of the 1970s, when Italian Marxist Antonio Negri was arrested for supposedly supporting the Red Brigade’s abduction and subsequent murder of politician Aldo Moro, had radical political theory been taken so seriously in the West.

Critics of the detention of the so-called “Tarnac 9” (named after the village where they were apprehended and later expanded to the “Tarnac 10”) understandably focused on the lack of concrete proof. Because the French government’s case depended heavily on the claim that The Coming Insurrection betrayed stylistic evidence of their authorship, attempts were made to downplay the supposedly distinctive character of its prose. The anonymity of the Invisible Committee was thereby framed, not as a function of its members’ need for secrecy but of the fact that the book recycles ideas that have been freely circulating on the Left for decades. According to this line of argument, the book can hardly be considered more dangerous than the work of its intellectual forebears, from Alain Badiou to Gilles Deleuze.

At times, this defense has veered into curious territory, with leftists implying that the French government was silly to take The Coming Insurrection so seriously. Just as Michel Foucault famously responded to Antonio Negri’s arrest in the 1970s by asking whether he wasn’t “in jail simply for being an intellectual,” these thinkers have been incredulous that the security apparatus could fail to acknowledge the gaping chasm between theory and practice. Some have even acted offended by the failure to comprehend that the language game of radical discourse is fundamentally antithetical to the production of any kind of “manual,” much less one intended for the use of prospective terrorists.

But unless the authors of The Coming Insurrection are merely striking a pose, this indignation does the book a grave disservice. Because its most striking feature, when compared to the works of most established academics on the Left, is the sincerity it communicates. While the book is by no means a manual in the sense that The Anarchist Cookbook was, it does proceed from the unwavering conviction that it is time for intellectuals to stop playing games.

When Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels composed The Communist Manifesto — a book with which The Coming Insurrection has a lot in common from a stylistic standpoint — they were explicitly forsaking the world of scholarship for the world of politics. That’s why their book wraps up, not with idealistic declarations about the meaning of communism, but pragmatic advice for the worker’s movements in different countries, specifically tailored to the current conditions within each of them. Marx’s eleventh thesis on Feuerbach, at that point still unpublished, distilled this principle to its essence: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world; the point is to change it.”

Even if the authors of The Coming Insurrection are steeped in philosophy, particularly leftist responses to the challenge of post-structuralism, that doesn’t mean that their goal is simply to do philosophy. In a passage that underscores their indebtedness to Marx, they make it very clear that interpretation by itself is impotent:

It’s useless to wait — for a breakthrough, for the revolution, the nuclear apocalypse or a social movement. To go on waiting is madness. The catastrophe is not coming, it is here. We are already situated within the collapse of a civilization. It is within this reality that we must choose sides.

To no longer wait is, in one way or another, to enter into the logic of insurrection. It is once again to hear the slight but always present trembling of terror in the voices of our leaders. Because governing has never been anything other than postponing by a thousand subterfuges the moment when the crowd will string you up, and every act of government is nothing but a way of not losing control of the population.

We’re setting out from a point of extreme isolation, of extreme weakness. An insurrectional process must be built from the ground up. Nothing appears less likely than an insurrection, but nothing is more necessary.

This is one of the more modest portions of the book. The frank acknowledgement of weakness demonstrates that their articulation of relationships within the global Left truly is the product of wishful thinking. But that moment of sober-minded realism goes hand in hand with the insistence that there is no time like the present to become politically engagé.

That’s one of the reasons I selected The Coming Insurrection for a class on New Media I was teaching last fall. Because most of the students were eighteen-year-olds in their first semester at the university, I knew we would be spending a lot of time talking about the way they use social media like Facebook and Twitter. But I was keen to help them achieve critical distance on their everyday pursuits. I wanted them to confront material that would seem stubbornly foreign, whether because it came from a time or a place substantially different from their own.

To that end, I made them read both the entirety of The Coming Insurrection and essays by Walter Benjamin written at a time when cinema and radio were still young and television was only in the experimental stage. If Benjamin’s work provided historical perspective, showing that the desire to make sense of New Media was hardly new, The Coming Insurrection was intended to demonstrate its geographical equivalent.

Given that most of the students in my class were Arizona natives from comfortably middle-class suburbia — in other words, about as far from the Parisian banlieues as it’s possible to get in the developed world — I figured that they would struggle with the strangeness of the book’s arguments. Past experience had taught me that students are far less willing to think outside the box about the present than they are about the past. Surely, I thought, the radical take on contemporary life put forth in the book would disturb some of them and anger others.

To my great surprise, however, the class had a harder time with Walter Benjamin than The Coming Insurrection. I had underestimated the degree to which growing up in the internet era would make it difficult for them to think of cinema as a medium distinct from other visual media. And I had greatly overestimated their resistance to the sort of bold theorizing featured in The Coming Insurrection. Even students who would proudly confess their political conservatism during class discussion expressed agreement with many of the book’s theses.

Because I had approached our session on The Coming Insurrection with trepidation, I had made it a point to emphasize the book’s radicalism. I highlighted the introductory note detailing the arrest of the Tarnac 9, noting that we were going to be tackling a text deemed truly dangerous. We were reading the book, I added, precisely because it offered a perspective vastly different from what the mainstream media in both the United States and France present. In retrospect, framing The Coming Insurrection in this way certainly played a role in the class’s response to the text. After all, many of the students had ended up in the Honors program precisely because they were unwilling to take what their teachers told them at face value.

Nevertheless, my experience of teaching the book in this context made me rethink my first encounter with it. Maybe it wasn’t quite as mired in “wishful thinking” as I had imagined. And maybe its Frenchness wasn’t so obvious to readers with little experience reading philosophical prose. Could it be that the very qualities that had activated my filter when I read The Coming Insurrection the first time were precisely the ones that made it a rhetorical success? To my mind, it was still full of exaggerations, prophetic when it could have been pragmatic, maddeningly diffuse when I desired details. But the authors’ willingness to reach out to an audience far removed from traditional leftist circles was clearly paying dividends I had not anticipated.

By transmuting the Marxist concept of class conflict into the much vaguer but more flexible notion of a war pitting the many against the few, The Coming Insurrection persuades readers to see themselves as potential rebels. The passage my class ended up discussing at the greatest length, the opening paragraphs of the book’s first chapter (“First Circle”) helps to illustrate how this works:

”I AM WHAT I AM.” This is marketing’s latest offering to the world, the final stage in the development of advertising, far beyond all the exhortations to be different, to be oneself and drink Pepsi. Decades of concepts in order to get where we are, to arrive at pure tautology. I = I. He’s running on a treadmill in front of the mirror in his gym. She’s coming back from work behind the wheel of her Smart car. Will they meet?

“I AM WHAT I AM.” My body belongs to me. I am me, you are you, and something’s wrong. Mass personalization. Individualization of all conditions — life, work, misery. Diffuse schizophrenia. Rampant depression. Atomization into fine paranoiac particles. Hysterization of contact. The more I want to be me, the more I feel an emptiness. The more I express myself, the more I am drained. The more I run after myself, the more tired I get. We treat our Self like a boring box office. We’ve become our own representatives in a strange commerce, guarantors of a personalization that feels, in the end, a lot more like an amputation.

After having read so much about how children who came to political awareness in the wake of 9/11 were unwilling to take risks — and having, unfortunately, added to that stereotype with commentary of my own — I was stunned to witness how thoroughly even conservative students were able to identify with this critique of contemporary selfhood. Ultimately, the remoteness of The Coming Insurrection’s geographic context, its “un-American” character, actually made it easier for my students to read it without prejudice, but only because the book’s authors worked so hard to make it accessible to a broad audience.

As the Occupy Wall Street movement started to generate traction, I found myself thinking back on my experience of teaching The Coming Insurrection. Amid all the attempts to single out the protesters’ intellectual ancestry — Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt’s Empire, the anarchist David Graeber’s anthropological approach to the topics of value and debt, the homespun populism of the Howard Zinn crowd, firebrands like Cornel West — I didn’t run across a single mention of the French book. But the more I thought about it, the more clear it became that The Coming Insurrection provides the perfect manifesto for those who want to take the movement to another level.

For one thing, the book is available for free, which never hurts. For another, its strategic vagueness, calling the many to rise up against the few, matches up quite neatly with the attempt to make a sharp distinction between the “99%” and its narrowly defined opponent. Perhaps most importantly, I now understand, The Coming Insurrection gives us the perfect description of how to regard a globally dispersed, ideologically heterogeneous resistance, not as a premature and problematic stage of development crying out for “organization,” but a politically meaningful end in its own right:

If we see a succession of movements hurrying one after the other, without leaving anything visible behind them, it must nonetheless be admitted that something persists. A powder trail links what in each event has not let itself be captured by the absurd temporality of the withdrawal of a new law, or some other pretext. In fits and starts, and in its own rhythm, we are seeing something like a force take shape. A force that does not serve its time, but imposes it, silently.

Language like this has nothing in common with nuts-and-bolts instructions on how to lead a cadre or build a bomb. But it could just be the case that the French government was right after all, if for all the wrong reasons: this book is a danger to our state of bondage.

NOTE: This is the third installment in Souciant’s “Occupy Theory” series, which is devoted to analyzing the intellectual underpinnings of the movement that Occupy Wall Street set in motion.

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit

You’ve basically missed the entire point of The Coming Insurrection. You’ve also ignored The Coming Insurrection’s own direct forebears. All and all, this is a pretty pathetic piece castrated of The Coming Insurrection’s positive content and its negativity. It’s not a matter of the many against the few. It’s civil war. The pacifiers, the demogogues, the recuperators are on one side of it.

I’ve been thinking about how to respond to your comment, “ANON,” but it’s hard. Personally, I have difficulty with people who say, “You’ve gotten it totally wrong,” without explaining WHY they think that. And I’m not fond of using castration as a metaphor, given the implication that NOT being castrated — and, therefore, being male — is the right way to be. Having said all that, though, I do feel an obligation to respond sincerely to your critique.

What I was trying to communicate in this piece is that The Coming Insurrection’s explicit internationalism — that making of connections between disparate events that I wrote about — makes it well suited to inspire participants in the Occupy movement, EVEN IF those participants lack the radical aspirations of the Invisible Committee. In particular, I do think that the generality of the book lends itself to readings — or MISreadings, as you would seemingly have it — that establish an equivalence between the invocation of “civil war” and the us-versus-them logic of rhetoric about the problem of the 1%.