A study conducted by the Hebrew University shows that most Israelis are aware that many of the Palestinians made refugees in Israel’s 1948 War of Independence were in fact expelled. Akiva Eldar thinks this is a landmark finding. I have to disagree.

It’s odd for me, as an American Jew, to argue with an Israeli about this. But I can only go from my own experience.

That experience started in the early 1970s, when, as a child, I began to learn my community’s narrative. According to that narrative, Israel was born pure; the Arabs of Palestine fled against the wishes of the Zionist establishment, not out of fear, but because they thought the Arab armies would “drive the Jews into the sea” after which they could return to their homes, minus their Jewish neighbors, and live happily ever after.

By the time I celebrated my bar mitzvah, I had already read some translations of very mainstream Israeli history books, and had spoken with more than a few Israelis. I knew the narrative I had been taught was a lie. And off I went to UC Berkeley, to study history, current events and politics, something that continues to this day, as a journalist.

Israelis always knew there had been significant degree of expulsions, both in the 1948 and 1967 wars. There might have been some differences about the extent of them. However, to find Jews who really thought the Palestinians left of their own accord, you had to come to New York, not Tel Aviv.

The real question is not what most Israelis know of their own history, but what they are, collectively, willing to discuss in public, and what they agree to project to the outside world.

Denial can be a very powerful, and often a very destructive, dynamic. It is virtually impossible, in interpersonal relationships, to bridge differences when one party insists on a false version of the past in order to validate their own self-image. Few of us can claim that we have never succumbed to that dynamic, at some point in our lives.

Nations are no different. This is hardly peculiar to Israel. Only in recent decades has the United States begun to come to grips with the genocide of Native Americans that was part and parcel of its founding. Mere mention of the Armenian Genocide continues to create sputtering fury in Turkey.

In 1963, when President John F. Kennedy characterized the treatment of the “American Indian” as “a national disgrace,” our conflict with Native Americans was over. In the ensuing years, consciousness grew of the crime that had been perpetrated against them. Slavery and segregation have become a part of US narrative, even while racism still exists, and we still have a long way to go to set these things right.

For Israel, which is still embroiled in conflict over the events it continues to collectively deny, it is more difficult. Neither African Americans nor Native Americans pose any threat or perceived threat to the US’ continued existence. Not so the victims of the Nakba, the Palestinian “catastrophe,” and the massive dispossession they suffered as a result of Israel’s birth.

It is this, more than any other single obstacle that needs to be overcome. But willful denial is very difficult to overcome.

Despite the rightward shift in Israel in recent years, Israelis as a whole continue to hold largely liberal values which are not easily reconciled with the massive dispossession of the Palestinians. This is part of the reason it is so difficult to admit — not so much to themselves, as to the rest of the world — that they know that hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were expelled during the War of Independence.

Israel’s massive advantage in political, military and economic power over the stateless Palestinians also makes it much easier to deny history, than to risk giving diplomatic credence to the Palestinian claim to the Right of Return to their former lands.

I understand that reluctance. As with many other aspects of the Israel-Palestine conflict, there are risks here for Israel, and not a lot of incentive for Israelis to take them. And that’s why the international community, and especially the United States, would have to uphold an accurate historical narrative if there is to be resolution and reconciliation in this conflict.

We all know that hasn’t happened.

This is why I question Eldar’s conclusion that the Hebrew University study’s findings are a sign of Israeli maturity. There is some maturation reflected there, but it is a stunted one, that is less of the grand step forward that it ought to be. Such maturity ought to have concrete political consequences. It’s hard, under present circumstances, to see what they might be, without a responsible leadership willing to cultivate it.

Tales of Israeli soldiers emptying Palestinian villages, like S. Yizhar’s novella Khirbet Khizeh, are as old as the state itself. That fact, combined with my own personal experience, which also pre-dates the revolutionary publications of Israel’s so-called New Historians makes me question whether this study represents real growth in Israeli society, or a phenomenon which has always been there, and which really illustrates a fault line between Israel’s public stances and what most Israelis really know to be true.

That same experience, however, also has demonstrated massive ignorance among Americans, Jewish and otherwise, of that same history. The fact that a repeatedly debunked book like Joan Peters’ From Time Immemorial (a proven fraud which attempted to show that the old myth about Palestine being virtually empty when the Zionists got there was true) can continue to be supported in the US (the noted propagandist and lawyer, Alan Dershowitz, cribbed a great deal of it for his books) when it was laughed off the shelves upon publication in Israel speaks volumes.

The Jewish immigrants to Israel from the US, and from the former USSR, who are currently helping to pull Israel to the right, may not have this background. However, their children, who grow up in Israel, as Hebrew-speaking Israelis, will. This is a potential basis for reconciliation.

Until the understanding of history this study refers to finds a real political expression, within mainstream Israeli politics, the practical benefits of a more “mature” Israeli society will unfortunately remain theoretical. Why perpetuate this age old-situation, when there is every incentive to overturn it?

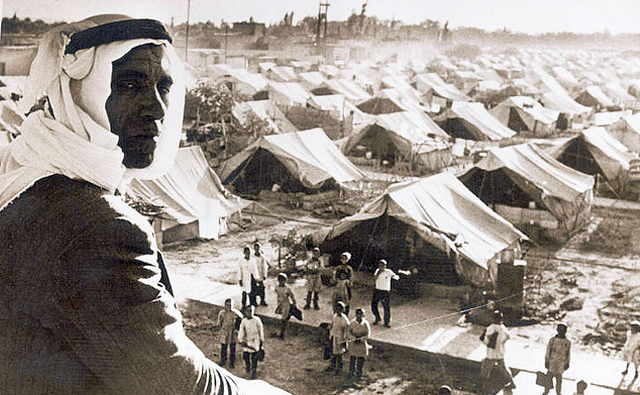

Photograph courtesy of gnuckx. Published under a Creative Commons license.

Great essay. Indeed, the acknowledgement of the crime of the Nakba is at the heart of the conflict, without which there cannot be true reconciliation. It will also help Israeli Jews and the rabid Zionist supporters to shed their delusional view of Israel as “the country that can do no wrong”, therefore make them more prone to compromise.

I think you have misread Eldar’s article. He states at the very outset: “A major new study by Rafi . . . shows that more of the Israeli mainstream than previously thought has adopted the critical approach on 1948. Nets-Zehngut contends that this trend preceded the advent of New Historians like Tom Segev and Benny Morris by several years.” He later states: “The study refutes the widespread claim that until the 1980s the Jewish-Israeli media were entirely beholden to the Zionist narrative.” I believe the “maturity” that Eldar sees is the non-credibility that many (“just under half” as referenced in the ’08 study though you refer to “most Israelis” in a Hebrew Univ. study) Israelis have given the “Zionist” narrative of the Nakba exodus going back at least a couple of decades.

Nonetheless, there has never been any official acknowledgment by the Israeli government of Israeli responsibility for what the Palestinians call their catastrophe. Why? You suggest some explanations; here are some others to add to the mix. Carlo Strenger, professor of psychology at Tel Aviv University concludes: “Israeli public discourse and national consciousness have never come to terms with the idea, accepted by historians of all venues today, that Israel actively drove 750,000 Palestinians from their homes in 1947/8 and hence has at least partial responsibility for the Palestinian Nakba … We are locked into a vacillation between self-images of either all-good or all-bad…†(Ha’aretz 08/06/07) Another Israeli analyst – Daniel Bar-Tal, referred to by Ha’aretz as “one of the world’s leading political psychologistsâ€, offers a similar view: “We are a nation that lives in the past, suffused with anxiety and suffering from chronic closed-mindedness.†On Nov. 1, 2009 Henry Siegman, rabbi and former Director of the American Jewish Congress, wrote in the NY Times: “The Israeli reaction to serious peacemaking efforts is nothing less than pathological – the consequence of an inability to adjust to the Jewish people’s reentry into history with a state of their own following 2,000 years of powerlessness and victimhood. Former Prime Minister Yitzchak Rabin … told Israelis … in 1992 that their country is militarily powerful and neither friendless nor at risk. They should therefore stop thinking and acting like victims. … This pathology has been aided and abetted by American Jewish organizations whose agendas conform to the political and ideological views of Israel’s right wing.†And finally, in the words of Jewish/American author Kim Chernin: “At its most vehement, our sense of ever-impending Jewish peril brings down on us a willed ignorance, an almost perfect blindness, to the endangerment of others and to the role we might play in it.â€

George,

I agree with some of what you say, but will let the rest stand.

One point–I said “most Israelis” because the study refers to just under half of Israeli Jews… I consider it a given that virtually all of Israel’s non-Jewish citizens will, at the least, take what is referred to as “the critical approach” in the article, thus clearly a majority of Israelis subscribe to it.

Great comment, George. Your choice of quoting psychologists hits exactly the heart of the matter: Israel is a country that cannot be understood without a psychological analysis as even I, without being a professional psychologist, concluded long time ago that it is suffering from a collective psychosis and needs treatment as it looks more and more detached every year, to the point of isolation. I don’t know if psychological treatment to an entire country is possible but perhaps more discussion in that direction would help.

I highlighted this detachment in one of my blog posts, about Israel’s planned “Museum of Tolerance”:

http://dancingwithpalestinians.wordpress.com/2011/07/13/israels-museum-of-tolerance/

Mitchell and Ahad: Another possible source and title that I ran across recently for the general problem that Chernin calls “willed ignorance”, Siegman calls “pathological”, Bar-Tal refers to as “chronic closed-mindedness”, and Strenger “self-images of either all-good or all-bad” can be found in the following paragraph from Joel L. Kraemer’s book Maimonides: The Life and World of One of Civilization’s Greatest Minds.

“The Masada Complex”

“Maimonides wanted to release Jews from their martyrdom obsession and esteem for sacrificial victims. The fall of Masada, a radiant chapter in the martyrdom repertoire, was an enduring national symbol. Masada is the fortress on top of a mesa-like precipice to the west of the Dead Sea, where 960 defenders defied the Romans, resisting for three years after 70 C.E. All hope gone, the men killed their wives and children, and threafter committed suicide rather than fall into the hands of the Romans. Readiness to sacrifice one’s family and oneself against hopeless odds in order to preserve one’s religious or national integrity or freedom has been called the “Masada complex.” The danger of transforming sacrificial narratives into national symbols is that a collective, like an individual, is liable to repeat past traumatic experiences obsessively (repetition compulsion). Post-traumatic stress leads to re-enactment, where individuals place themsleves in the same situation repeatedly, compulsively re-creating the moment of trauma or an aspect of the traumatic scene in literal or disguised form, or returning to the scene, perhaps to alter the outcome. They also tend to use projective identification onto others of roles essential for their reenactments. (my bold) One may conceptualize repetiiion compulsion and projective identification as an attempt to integrate the traumatic scene into life in order to master it.” pp. 114-15.

Kraemer takes us on an apparently pretty big jump in the midst of a very detailed biography of Maimonides, so I believe most of this is obviously Kraemer himself speaking rather than paraphrasing Maimonides. Nonetheless, Kraemer’s suggestion regarding the long history and deep roots of our “repetition compulsion” is not only interesting but also perhaps very provocative regarding the pickle we’re in.

Among the sources footnoted by Kraemer for this paragraph are:

Nachman Ben-Yehuda The Masada Myth: Collective Momory and Mythmaking in Israel, Yael Zerubavel Recovered Roots: Collective Memory and the Making of Israeli National Tradition and Judith Herman Trauma and Recovery