In 1977, Chelsea released Right to Work. As with the term “public school,” “right to work” has opposite meanings in the US and UK. In America, it means the “right” of the government to override closed shop agreements between unions and employers, a contractual agreement companies should support. Except, since closed shops benefit unions, pro-market advocates don’t support it, and hypocritically call for state regulation. In the UK, “right to work” is less Orwellian. It means what says: the right to a job. Chelsea’s 1977 song noted the irony of the British right-to-work principle versus the ugly reality of unemployment and long dole lines. It’s as good a starting point as any to talk about the thread of anti-capitalist sentiment that runs through punk.

That same year, Los Angeles band The Dils were singing Class War and I Hate the Rich. In the US and the UK there was an inchoate sense that punk was going to be a new, working class type of rock and roll, even if it would take the triple occurrence of the 1980s, Reagan, and Thatcher for these amorphous ideas to coalesce into a mainly leftist cultural movement with generally anti-capitalist (or at least strongly anti-corporate) sentiments. Whereas British punks were often politically galvanized by Rock Against Racism (and, later, CND) festivals, the US hardcore movement’s corollary, the Rock Against Reagan festivals) (usually headlined by the Dead Kennedys, and organized by the Yippies), likewise helped politicize fans of that genre. For the punk, post-punk, and hardcore movements as a whole, racism, nationalism, sexism, warmongering, and cultural conservatism were the main topics and primary villains. Economics seemed bound up in the whole rotten deal, but it was less explicitly dealt with.

Below are fifteen songs which highlight the anti-capitalist side of the punk, post-punk, and hardcore punk movements. There’s no shortage of songs of this nature, especially if one takes into consideration the ongoing and international scope of the underground DIY punk/crust/noise phenomenon. I didn’t list a single Crass or Dead Kennedys song, because that seemed too easy. (And those two bands are dealt with many times throughout this article, in any event.) In punk, “the state,” “society,” and “the system” are targets of ire often enough; the concern here is with those instances that deal with the economic side of the equation.

Indeed, the anti-capitalist side of the punk, hardcore, and post-punk movements is important to remember in an age where American-style Libertarian capitalism of the Ron Paul variety seems to be growing in popularity, especially among the young. Punk has always been socially and culturally libertarian: legalizing drugs, repealing anti-sodomy laws, and advocating free speech have been part and parcel of the punk phenomenon from day one. Most involved in the punk milieu are fierce advocates for gay marriage and are pro-choice, too, even if Dr. Paul is neither of these. (See, for example, Ron Paul’s pro-life stance) The antiwar aspect has also always been there, despite punk’s traditional disdain for hippie-like peace-and-love treacle; even a band as homophobic as Fear could always at least agree that war sucked (Let’s Have a War.)

When punk and post-punk bands have dared to directly tackle the thorny subject of economics they’ve generally come down against capitalism. Few punk or post-punk bands sing enthusiastically about capitalist utopias where, as in Ron Paul’s ideal world, America’s Civil Rights Act of 1964 or the Americans With Disabilities Act are repealed because they abridge business owners’ property rights. Few punk bands wax idealistic about a world where overtime laws or the minimum wage are removed because they unjustly constitute “state interference in the economy” — and that is indeed what radical free marketers feel they are.

Being socially and culturally libertarian is one thing. “Economically libertarian” is a different matter. In Europe, “economic libertarianism” is taken to refer to what the Spanish antifascists of 1936 fought for: a democratic economy administered by a combination of workers’ councils and other popular assemblies, with guaranteed economic minimums. Long-running Dutch postpunk band The Ex sang, in their “1936” EP about that era, “The bourgeoisie was not needed and we proved it / No church, no masters, no guardians / Property collectivized, we took over the estates / No necessity for money to exist, everyone would work / And exchange with other collectives – no need for the state.” (The Ex, “People Again.”)

In America, the term “economic libertarianism,” would probably be taken to mean a system of capitalist property rights whose enforcement is paid for by the general public through taxation. And yes, I realize extreme anarcho-capitalists don’t even want that, but desire a more radical “free market” society where all police forces are private security companies, all courts are privately-owned arbitration firms, all roads are private toll roads, and the fire department won’t put out the fire in your house if your fee-for-service subscription payments to the fire company are past due. I haven’t found many punk bands singing in support of private security companies – in fact, quite the contrary (see Crass’s Securicor) — but I suppose they’re out there. In other words, American economic libertarianism is a system of privatized profits subsidized by the public (who may be poor or rich but who pay for the same system of private corporations regardless, just as now.)

As with the terms “right to work” and “public school,” which mean different things on different sides of the Atlantic, so “economically libertarian” has different connotations, depending on which side of the pond you’re on. One sense connotes a type of grassroots, popular democratic socialism (what Noam Chomsky calls libertarian socialism); the other refers to raw, unfettered capitalism let loose upon the land.

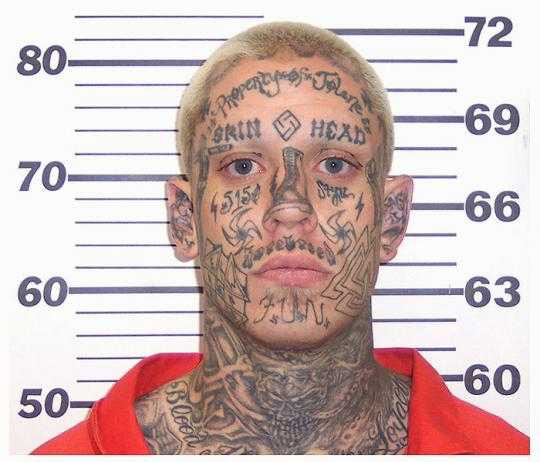

Ultimately, you can’t tease out a truly consistent economic message from the punk movement. Consistency of any sort is hard to come by at all, especially in the early days of 1976 to 1978: Witness hammer-and-sickle t-shirts worn alongside swastika armbands, when punk was still a bubbling brew of shock rock sensationalism and people trying on different radical ideologies for play. Black Flag released White Minority shortly after a Jewish Siouxsie Sioux sang about “too many Jews for my liking” in her original version of Love in a Void. The Dwarves, GG Allin, The Mentors, S.O.D., and The Meatmen remind that you can’t neatly squeeze the entire, sprawling punk corpus into strict parameters. It really took bands like Crass to put serious political teeth into the punk movement, even if Crass themselves would later speak with disdain about “politics.” Sean McGhee of anarcho-punk band Psycho-Faction explained that in punk’s early days, “the three C’s of political punk” were “Crisis, The Clash, and Crass.” All three bands claimed to be anti-capitalist, and they merit a little attention.

Crisis were, in fact, directly tied to the Socialist Workers’ Party, and most band members were Trotskyite. (This was also the case with the Angelic Upstarts, a formative band in the Oi! movement.) The Clash professed to be supporters of the third world solidarity movement, and sang the praises of Central American Marxist revolutionaries (Sandinista!) as well as the Spanish anti-fascist socialists of the 1930s (Spanish Bombs.) Whether The Clash were “really” revolutionary is a subject for another time; there was plenty of cartoony revolutionary sentiment going around – like The Adicts’ Viva La Revolucion or even the Sex Pistols’ “Anarchy in the UK” – and the degree to which The Clash earnestly felt what they sang about is open to question. Crass opened the Pandora’s Box of serious political anarchism into the context of punk rock. Over the years this has developed into a sprawling, underground, international DIY punk scene that cranks out hundreds of bands to this day. Sean McGhee, mentioned above, went on to curate the well-received, 4-volume Anarcho-Punk CD series on Overground Records, the final volume of which was titled Anti-Capitalism and featured a 24 page booklet written by Crass’s Penny Rimbaud.

So, here are fifteen songs that deal with the economic, anti-capitalist side of punk. The list is not exhaustive.

1. DOA – Class War (1982)

DOA’s Hardcore ’81 LP is a well-known contender for “first hardcore punk LP” status. With tracks like “Smash the State,” “Race Riot,” “Slumlord,” and “General Strike,” it is as aggressive politically as it is musically. “Class War” is the Canadian punk band’s cover of The Dils song from 1977 mentioned at the beginning of this article, with some slightly altered lyrics: “I want a war between the rich and the poor. […] / If I´m told to kill, in Beirut or El Salvador / There will be a class war, right here in America.” Of course, The Exploited also had a song called Class War, but they’re still The Exploited. This song is off DOA’s War on 45 EP.

2. Gang of Four – To Hell With Poverty (1981)

Sometimes it’s tempting to think of Gang of Four as the sort of band that the Frankfurt School of Marxist theory might have put together, had punk occurred in the 1940s. Fashionable, danceable, cultural Marxism – what’s not to love? “To Hell With Poverty” was released in the US on the Another Day, Another Dollar EP (and in the UK as a single) and shows the band branching off into funk-drenched, mutant disco. It’s a song about getting wasted on cheap wine and dancing the night away to forget the misery of living in poverty — like something George Orwell would have written about in Down and Out in Paris and London.

3. Subhumans – Businessmen (1985)

As Noam Chomsky and others have pointed out, the real Adam Smith (as opposed to the ficitious Adam Smith invented by historical revisionists) was suspect of the motives of businessmen and their involvement in government. In 1776 Smith said that businessmen are “an order of men whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.”You might think Dick Lucas had read that passage before writing this Subhumans (UK) song. Businessmen, off their 1985 Worlds Apart LP.

4. The Proletariat – Marketplace

Boston’s The Proletariat, to me, are one of the most exciting and underappreciated postpunk bands of the early 1980s. Like The Minutemen and The Urinals/100 Flowers, The Proletariat were a fundamentally postpunk band that got lumped in with the US hardcore movement, probably due to the band’s appearance on the This is Boston, Not L.A. compilation. Sounding at turns like Gang of Four, PiL, and even Theatre of Hate, The Proletariat took their convictions seriously: “Religion is the Opium of the Masses” and the Gang of Four-esque Voodoo Economics are two other fine moments, as is their entire, criminally overlooked Indifference LP. In Marketplace the band complain that “the myth of Horatio Alger can still be found in books / But it’s taken as gospel.”

5. MDC – Business on Parade (1982)

To some it’s no small irony that some of the most queer-positive, cop-hating, and anti-capitalist punk rock came from Texas in the late 1970s and early 1980s. MDC, The Dicks, DRI, the Big Boys, AK-47, and Really Red all had stridently anti-police, pro-gay, and anti-right wing lyrics. Although MDC, The Dicks, and DRI would move to San Francisco and live with the Crucifucks and Crucifix in the sheltering, protective shadow of the Dead Kennedys, all of these bands would give punk a powerful political shove leftward in the Reagan era, helping to define the overall ideology of the hardcore movement. MDC were one of only two American bands to get a release on Crass Records, and their debut LP on their own R Radical records (whose catalog consists uniformly of anti-capitalist punk rock) was a blistering assault on all forms of authority: patriarchy, homophobia, the police, and, yes, corporate rule.

6. Propagandhi – And We Thought Nation-States Were a Bad Idea (1996)

Although Propagandhi are still going strong, they’re a band I associate with the 90s and the Seattle WTO/anti-corporate globalization protests. While Rage Against the Machine were attracting people into anti-capitalist politics from the mainstream, Propagandhi was providing a soundtrack for either ex-skaters who had gone to grad school to be the next Noam Chomsky, or those who were already forming anarchist black blocs on the ground. The 1990s era of Propagandhi sounds dated to me now – it reminds me of the Lagwagon-style Fat Wreck Chords sound of a lot of bands of that era, which is not too far from how teenage mall-punk has come to sound nowadays. Well-meaning late 90s political punk like Good Riddance’s Ballads from the Revolution, Anti-Flag’s A New Kind of Army, and the Suicide Machines’ Battle Hymns have not sonically aged well, though they were Hot Topic faves and were all fairly radical in content lyrically. Nevertheless, Propagandhi are a “movement” band if ever there was one. “Nation-States” is a yrical whirlwind of anti-capitalist themes.

7. The Pop Group – We Are All Prostitutes (1980)

Like early Gang of Four, The Pop Group were an agit-prop postpunk band. They were a huge influence on Nick Cave and The Birthday Party. “Capitalism is the most barbaric of all religions,” Mark Stewart growls in “We Are All Prostitutes.” “Rob a Bank” also gets an honorable mention, off the For How Much Longer Do We Tolerate Mass Murder? LP – a stomping funk-punk song (with horns) that advocates outright wealth redistribution via direct action (i.e. bank robbery). Mark Stewart is still at it; a new release called The Politics of Envy, a phrase heard often in the ongoing 2012 US presidential campaign, is in the works, with ex-members of Crass.

8. Avskum – Fight Back Capitalism (2002)

Avskum are a long-running Swedish kang-style hardcore band who, like a lot of the Scandinavian and Japanese hardcore bands of the 1990s, took Discharge’s influence and ran with it. Whereas most d-beat bands of this style bellow endlessly about “the state” (or even more generically, “the system”), Avskum actually tackle capitalism by name, too. “Fight Back Capitalism” starts off sounding like it will be a cover of The Stooges’ “Now I Wanna Be Your Dog,” but the gloves come off and it becomes a blistering, hell-for-leather barnstormer in the band’s best dis-core style. Avskum’s 2002 Punkista LP was part of a d-beat renaissance that took hold from about 2002 until 2006, a renaissance that also prominently featured fellow Swedish bands Wolfbrigade, Skitsystem, and Totalitar. Their 2008 LP, Uppror Underifran, continued the theme with “Kapitalismens Yttersta Dagar” (“Capitalism’s Last Days”) and “Capitalism is Terrorism.”

9. Killing Joke – Age of Greed (1990)

In many ways, Killing Joke’s 1990 Extremities, Dirt, and Various Repressed Emotions LP is the band’s most radical statement. A return to angry form after 1988’s embarrassing Outside the Gate (which featured an attempt at hip hop), it opens with the stomping “Money Is Not Our God” and barely lets up from there, continuing through to “Inside the Termite Mound” after the song here, “Age of Greed.” Some of Jaz Coleman’s lyrics about businessmen are just genius: “There is too much fat on your heart, pig / A lifestyle of cholesterol – cross-collateralized cholesterol / Saving what’s left from the profit margin – for what? / For some conscience-easing charity? But why? Just to justify!” And then there’s the memorable refrain “feather the nest and fuck the rest” – the guiding principle of society, the song warns, akin to what the labor movement of old posited was the guiding motto of capitalism, “We gain wealth forgetting all but self.” The LP may have been motivated by Killing Joke’s getting screwed over by greedy record companies, turning them sour on the entire profit-driven system, but like Fugazi’s Repeater LP – which came out the same year, and which has songs with titles like “Greed,” “Merchandise,” and “Turnover” with similar themes — it forms a cohesive and angry economic statement.

10. DRI – Capitalists Suck (1982)

By 1983, the race was on to be the fastest band on the planet, with Larm and Siege leading the way. DRI weren’t too shabby in this department, either, although to anyone not on sufficient amounts of speed it probably all sounds like a noisy racket. DRI would mature their sound into crossover thrash while retaining their political edge (“Suit and Tie Guy,” “Acid Rain”), but early on formed a core of speed-obsessed political bands with fellow Texans MDC. DRI’s “Reaganomics” is another swipe at GOP economic policy in the same vein, and off the same 1982 Dirty Rotten EP/LP.

11. Anthrax – Capitalism is Cannibalism (1982)

Crass Records anarcho-punk band Anthrax (as opposed to the US metal band of the same name) came out with a graphic in the 1980s that stated, “Capitalism gives opportunities in life. Anarchy gives life.” I’ve always found the wording in that statement to be cringe-worthy. Capitalism gives opportunities in life for the wealthy, sure – but for the poor? Oh well, we all know what they probably really meant. In any event, after releasing the Capitalism is Cannibalism EP, the band went on to Small Wonder Records and are currently back together, like many bands of the era. Anthrax and the dozens of other bands in the orbit of Crass and the early 80s UK anarcho-punk movement could fill a book, and have: See Ian Glasper’s The Day the Country Died.

12. The Pist – Black and Blue Collar (1995)

The Pist are a 1990s US punk band that have aged well, thankfully. They have done a few reunion shows over the past decade, but no new material seems to be in the works. Their finest moments were probably “The Customer is Always Right” and this song, “Black and Blue Collar,” a great rant that blends Black Flag-style working class resentment (a la “Clocked In”) with a mid-tempo USHC approach (a la the Negative Approach song Nothing.) The lyrics are genius, too: “How much of our precious lives are going to waste? With all the fucking years that are spent in the workplace? / And blue collar pride is a fucking shame /A capitalist’s excuse just to play the system’s game / Possessed by your possessions, the mortgage and the bills, / The death we bought is slow, but we own it, and it kills.”

13. The Dicks – Bourgeois Fascist Pig (1983)

A self-described “commie faggot band” led by the incomparable Gary Floyd, The Dicks came racing out of the gate in an explosion of hammers and sickles, anti-cop vitriol, flamboyant crossdressing, and punk iconoclasm taken about as far as it could go. “Rich Daddy” is a classic cocktail of Texas blues, hardcore punk, and underclass resentment. “Bourgeois Fascist Pig” is an equally angry diatribe against bosses everywhere. Chumbawamba’s Revolution and Born Against’s Well Fed Fuck are other great songs in this same “hate my boss/hate my job” vein.

14. Newtown Neurotics – Living with Unemployment (1983)

If there was a “labor movement school of punk rock,” Newtown Neurotics’ “Living with Unemployment” would be at the forefront. Even if it is basically a re-working of The Members’ Solitary Confinement, the song as the Neurotics recorded it could have come straight from the pen of Billy Bragg. Any labor movement school of punk would also have to include the street punk/Oi! Music of bands like the Angelic Upstarts (who were explicitly socialist) and The Business (i.e. Work or Riot?).

15. Sin Dios – Requiem (1991)

In many ways, Sin Dios are the ultimate anti-capitalist anarchist punk rock band. From Spain, they embraced the black and red colors and heroic imagery of the anarcho-syndicalist CNT-FAI of the 1930s. Whereas postpunk band Durutti Column merely named themselves after an anarchist militia, Sin Dios – which means “Godless” – effectively turned themselves into the musical version of one. Except for a turn towards the fashionable ska of the late 90s, the band remained a solid hardcore band until they broke up in 2006. (And what Sin Dios were to Spain, so the great communist punk band CCCP were to Italy). “Requiem” is off Sin Dios’ Ruido Anticapitalista (“Anticapitalist Noise”) LP.

Photograph courtesy of Joel Schalit

Chelsea’s lead singer, called Gene, if I remember right, told the NME that ‘The Right to Work’ was about his dad who had been excluded from his job because he was not a union member and it was a closed shop – which was a bit of a disappointment to all of us who thought it was a right-on protest against unemployment.

Chomsky is most often right; but his lack of grasp of the importance of abolishing the wage system shows all too often in his rather naive views of political-economists like Adam Smith. ”It is ill provided with Wood; two articles essentially necessary to the progress of Great Manufactures. It wants order, police, and a regular administration of justice both to protect and to restrain the inferior ranks of people, articles more essential to the progress of Industry than both coal and wood put together, and which Ireland must continue to want as long as it continues to be divided between two hostile nations, the oppressors and the oppressed, the protestants and the Papists.” Adam Smith to Lord Carlisle 1779 Wood was an essential ingredient in the construction of war ships of that era. full:http://oll.libertyfund.org/?option=com_staticxt&staticfile=show.php%3Ftitle%3D203&chapter=58077&layout=html&Itemid=27

I thought that “White Minority” was ridiculing white flight?

An Alternative to Capitalism (since we cannot legislate morality)

Several decades ago, Margaret Thatcher claimed: “There is no alternative”. She was referring to capitalism. Today, this negative attitude still persists.

I would like to offer an alternative to capitalism for the American people to consider. Please click on the following link. It will take you to an essay titled: “Home of the Brave?” which was published by the Athenaeum Library of Philosophy:

http://evans-experientialism.freewebspace.com/steinsvold.htm

John Steinsvold

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result.”~ Albert Einstein