‘90s punk. What was it? Think of punk in the 1970s. A certain set of images, band names, and song titles immediately present themselves: The Ramones, Sex Pistols, the Buzzcocks. Fast forward to the eighties, and a similar thing happens, even if many 1970s bands continued into the decade, and even if many bands thought of as 1980s bands, like Black Flag or the Dead Kennedys, actually began in the ‘70s.

But punk in the 1990s is a bizarre beast. No definitive history or playlist presents itself. What happened?

When I first got into punk in the late 1980s, it was largely an offshoot of my teenage interest in skateboarding. In fact, Thrasher Magazine had a lot do with it. Until I started trading tapes with friends, I thought punk was something that was over, and had been replaced by speed metal of the Slayer variety. This was a silly idea, remedied in part by seeing strange and exotic band t-shirts I would see advertised by Sessions advertisements in TransWorld Skateboarding, t-shirts that boasted weird band names like Youth of Today or Abrasive Wheels that until then I had not heard of.

Pushead’s punk column in Thrasher, and my eventual discovery of Maximum RocknRoll and its reviews of current bands, helped change my view. But by then it was too late, and 1991 happened, The Year that Punk Broke. In reality, the David Geffen VHS of that name was mostly a scattershot cocktail of bands as disparate as the Ramones, Gumball, and Dinosaur, Jr. I still thought bands should sound like Negative Approach, not trippy, acid-soaked grunge rock. “Punk” suddenly entered a total state of confusion for me. Bands of disparate styles, tempos, dress, and cultural resonance all simultaneously fit under the “punk” umbrella.

I think it was Jeff Bale, who said that every decade since the 1950s neatly provide one cataclysmic advance in the rock ‘n roll trajectory: In the ‘50s it was the birth of rock ‘n roll proper; in the ‘60s it was the 1966 garage punk phenomenon of bands like The Monks and Velvet Underground and Zakary Thaks, that the Nuggets and Pebbles compilations catalog so well. In the 1970s, it was the ’77 punk rock explosion itself. In the 1980s, it was ’82 hardcore. But – the nineties? Things got more complex.

“The decade of the woman” in rock (that is, the 1990s) meant bands like Hole, Garbage, and Luscious Jackon, and pop singers such as Tori Amos and Alanis Morrissette, catapulted to stardom. Jill Sobule and Fiona Apple rounded out the edges. In the punk world, riot grrl seemed like a possible next step forward. Washington, DC and Olympia, Washington supplied a simultaneous one-two punch of post-hardcore bands like Fugazi and Jawbox along with the standard-bearer bands of riot grrl, Bikini Kill and Bratmobile. Lazily, groups like L7 and The Gits got included in the “new angry female punk” mix.

Of course, women have always played a larger role in the punk movement than in any of its rock ‘n roll forebears. Riot grrl seemed like a possible answer to the “Where is punk headed now?” question. The post-hardcore of Circus Lupus/Monorchid, Jawbreaker, and Bluetip seemed another answer. The Pist and Naked Aggression (another female-fronted band that folks once also tried to peg as “riot grrl”) kept the fort for purist, traditional punk rock. Everything was spitting apart, in a million different directions.

“Rapcore” – hardcore infused with hip-hop elements – also took off into a world all its own, evinced by bands like 25 Ta Life, Rage Against the Machine, Downset, and mid-90s Shelter. In fact, the HALO 8 documentary NYHC, filmed in the 1990s, captures this rap-hardcore hybrid moment in time, focusing on a thug-posturing NYC hardcore scene that in retrospect looks self-mockingly cartoonish and even a little embarrassing. This was the era of Biohazard teaming up with Onyx. Chunky guitar riffs and hardcore singers making hip hop gestures as they sang about how tough the streets had made them. This is a style of “hardcore” that exists to this day.

Krishna bands like 108 and the post-hardcore, Shelter-affiliated Baby Ghopal popped up. Screamo and hardcore/emo type bands like Moss Icon and Merel also seemed to be going a different route; look at the catalogs of Ebullition and Vermiform Records, led by Born Against. All of this was complicated by the media’s sudden fixation on heavy guitar-rock type bands, a fascination that led to bands like Helmet and Rocket from the Crypt and the Supersuckers achieving momentary flashes of success, while safer guitar bands like The Presidents of the USA and Everclear dominated the airwaves, bands that also bragged about their punk origins. By the end of the 1990s, Reverend Horton Heat, the Brian Setzer Orchestra, the Cherry Poppin’ Daddies, and the Squirrel Nut Zippers all brought back the bowling shirt. Mustard Plug, the Mighty Mighty Bosstones, and Suicide Machines brought back a certain form of ska-punk. Pick up a magazine that promised news on the latest punk bands in 1998, and you may be reading about everything from the political punk of Propagandhi to the latest pop punk of bands like Hagfish to something like Extreme Noise Terror. In a way, it makes no sense.

In fact, there was a period in the late 1990s where I thought I probably was not really into punk, since, after all, the term seemed so impossibly diluted as to be meaningless. It’s arguable “punk” is still in this garbage basket state, like the terms “emo” or “hardcore,” which mean different things to different people, depending on their own personal take on what these genres signify. I remember ordering a Very Records catalog and getting stuff in the mail from Revelation and Victory Records, never knowing what to expect in these years, and deciding that punk culture had probably gone off the rails and was no longer something that was a good fit for me. Would the record I ordered from these “punk” catalogs actually be a rap band with guitars, like Crown of Thornz, would it be a folksy jangly pop band like Beat Happening, or would be it be something like Swiz — or would it be some powerviolence, grind-y type band? No telling. It was all punk of some sort, supposedly, according to the descriptions.

Another dimension to the 1990s is what was happening overseas, especially in Scandinavia and Japan, where many argue the torch of actual hardcore punk had been passed during this bizarre era. In Sweden, the influence and fallout of Anticimex loomed large as Wolfpack, later Wolfbrigade, started up, and the deluge of “kang-style” hardcore, as its called, began. Several thousand miles away, Japan cranked out bands like Tetsu Arrey and Bastard. In the USA, His Hero is Gone and Dropdead forged another possible way forward. These bands would go on to inform the early 2000s d-beat renaissance that included Tragedy, Inepsy, and Born Dead Icons.

In short, the 1990s found punk splitting apart at the seams, as the Internet, and the media-driven success of bands like Nirvana encouraged a resurgence of people starting bands in every sub-niche that the klieg light of mainstream acceptance had shone onto punk culture. Underground music is still dealing with the cultural fallout of this era. There are no simple genres anymore, like “punk” (itself already a sub-genre of rock ‘n roll.). Only sub-sub-niches exist. Sometimes one is tempted to think that the postmodernists had it right, thirty years too soon. Everything is a nonsensical jumble. Purists will be frustrated at every turn.

The definite history of 1990s punk has yet to be written. Then again, maybe like Crass said as early as 1979 – “Punk is dead.” And there is no ‘90s punk. Or anything after. And yet music still gets made by bands who, for better or worse, think of themselves as forging ahead in that territory. What was “the ’90s punk scene”? What were its major bands? What is its history? Who will make a documentary like American Hardcore, which goes up to 1985, but about the nineties? What would that look like? Is it even possible? It’s time somebody wrote it down.

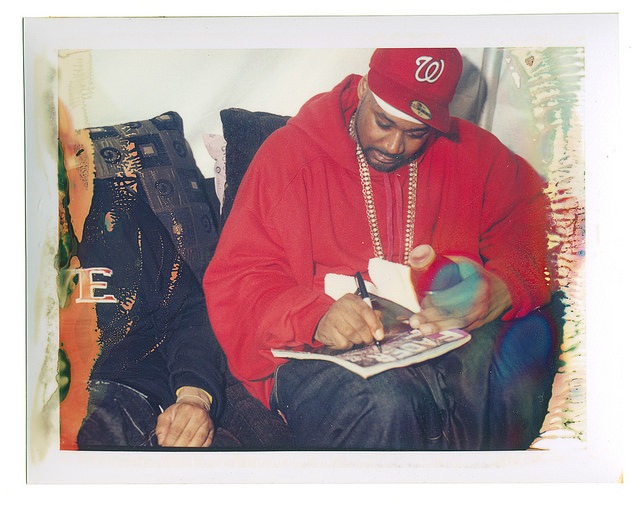

Photograph courtesy of David Shankbone. Published under a Creative Commons license.

Awesome article.

I feel like you left out the popularization of punk. No mention of NOFX, Bad Religion, or how Epitaph and the Punk-O-Rama crowd managed to popularize the genre while also watering it down.

I could see how this omission might be intentional, though. Many people can’t call that music punk with a straight face.

Thoughts?

Actually, a good friend of mine and I decided in 1989 that punk was officially dead and that Christ On Parade was the “seal of the punk prophets.”

Mentions of Green Day and Rancid bringing “punk” to the masses are conspicuously absent as well. Lots of “punk” sounding groups were part of the immediate and post-grunge fallout, where the record companies would sign a guitar-driven act and be quick to hype up their indie roots or “punk” background.

Then of course, there is also Blink-182, who heralded the flood of “pop-punk” bands into the mainstream…but they suck and was too busy listening to Subhumans, Aus-Rotten, and HHIG in the late ’90s to pay attention to them. 🙂

I meant I was too busy listening. Shame on me for lousy proofreading.