As I fumble through my tote bag, a cat scurries past my feet. I find what I’m looking for: a can of flat black Krylon spray paint. The top is already off. As a graffiti writer in NYC, I’ve learned to be prepared. I lift the nozzle and point at my target – an old rusted sign nailed into a stone wall of a building. It reads: “Arabs, don’t even THINK about looking at a Jewish woman.”

The letters bleed down the wall as I spray like the elevator scene from The Shining. I sound out the phoneme’s to my tag name. Scam One.

Suddenly a man’s voice shouts out “Yehudi!” (Jew) in an Arabic accent. In an alley that will only lead to nowhere (or somewhere that I don’t belong), I scatter up the two story building by grabbing onto a window gate and sticking my feet in between the large stones on the wall. From there I jump from one domed roof top to the next like a ninja (except slower and less coordinated.)

The next day, I return to see my work. Nothing much. Just a scribble and a whole lot of drip. But it gets my point across. Scam One.

It was 1986, and at the time, to the best of my knowledge, there was only one other graffiti writer in Jerusalem, He goes by the unimaginative name of David. He gets up and gains some rep, but pisses me off when I read in an article him describing writers in New York as ‘vandals’, but writers in Boston being ‘true’ graffiti artists. Of course the press falls for this bullshit, so obviously the toy needs to be schooled. I go out late that night and put a nice big throw up over his name in Mahane Yehuda, Scam One.

A year before arriving in Jerusalem for the second time, to follow my mother’s bliss, I had started a crew called NSB (Non Stop Bombers) in uptown Manhattan with two other graffiti writers, Dev and Nice.

This was my first attempt at putting together an artist collective. It quickly fell out of my hands. The new members, who were far less considerate began writing over other writers’ pieces, which, of course, lead to violence.

One of the writers from another crew attacked one of our own, and the members of NSB wanted to know what we would do to retaliate. My grandfather, who taught me how to draw, was a war artist in WWII, and had drawn by hand the battle of Normandy, as he had fought it. In that situation, war brought the art. In this case, art brought the war. This was one battle that I didn’t really understand.

I was afraid to leave the house. Even my own friends were threatening me, scared of getting a beat down themselves.

My mother decided the best thing to do would be to take me to Jerusalem, the place of my birth, for three months. We ended up staying there for three years.

This was a traumatic experience as the last time I went to Israel/Palestine, several years before, my god mother took me to meet a Sheik in the Palestinian refugee camp of Balata.

It was then that I realized there was a dark side to Israel that was being hidden from me. I wanted to know about it, as much about it as possible.

Being a child in NYC in the early 1980s was terrifying. It was like 9/11 every day. I was jumped daily, forced to smoke PCP, sprayed in the face with my own paint… Yet, despite having such experiences, I was unprepared for the chauvinism I encountered in Israel. It was completely foreign to me.

When I asked Israelis to explain the truth that I saw, they usually said, “Oh well they’re very poor. We can’t all be so lucky to enjoy the beauty of Israel!” Well, If beauty is in the eye of the beholder, then only the Israelis are the beholders because all the Palestinians were seeing was the backyard, and once I got a glimpse of it I never forgot it.

Frustrated, I came back to New York from that trip a little tougher, a little more aware that there was true injustice out there, and it could happen anywhere if you let it. I had almost gotten a glimpse of it in New York with NSB, my own small tribe. But now I was coming back to Jerusalem, and the ball was in Israel’s court.

I had no one I could relate to when it came to these political issues, graffiti was my only outlet. As a graffiti writer in NYC I had gone through several names, changing them almost monthly, as I was always paranoid, and still am, of being identified with one style. My frustration with this Israel, which kept fueling its citizens with this idea of unity, of wholeness, of being ONE nation, was really a lie, a SCAM. Scam One.

My tag names foreshadowed not only where I was at, but where I was going, as an artist. Scribbling these letters on walls in abstract ways became like a tarot card, written in Wild Style on a wall of a place either I would return to later or never forget.

Graffiti led me to understand that everything is not as it seems. Letters may say something, but they are abstract, and have many more meanings the more abstract they become.

Once there are so many meanings, they lose their meaning entirely and then reshape new realities. These new realities formed my life. This was something only the early Kabbalist’s had keyed into, I learned.

For instance I used to write Scribe. Then, one day I was in a record shop, the same one where I got my first dub record, Garvey’s Ghost, and a name on a record caught my eye. It was of the Russian composer Alexander Scriabin, who’s music foresaw serialism, the atonal system of Arnold Schoenberg. His name reminded me of my name Scribe, but Scriabin had more letters that could be weaved together in Wild Style. Little did I know that over a decade later his music and ideas would open my mind to the relationships between colors and sound, which eventually led me to become equally comfortable with the abstraction of avant garde music, and the minimalism of electronic dance music, as I only heard it as frequencies, colors.

During these three years I came to experience just about everything you could possibly experience in Jerusalem, without being mortally wounded. I lived in the ultra orthodox neighborhood of Mea Shearim, where I eventually ended up studying Judaism and became familiar with anti-Zionist Hassidic sects such as the Neturei Karta, heard Yemenite rhythms and Ethiopian choral music, smoked hash at the Golgotha (the supposed site of Christ’s crucifixion), attended Kung Fu films with my mother’s boyfriend, who would occasionally dump me with a group of insane cult followers while he would go to score dope. In fact I could probably write a book for every week I spent there.

After all of this, I finally returned to NYC, with a combination of religious fervor, and a primitive memory of hip hop. Assuming I was still going to have the beef I left behind, I came back wearing my old pin striped Lees, black and white Adidas with fat laces, a mosaic of 80s b-boy style. and hasidic chic. As soon as I could, I returned to my old neighborhood full of excitement to finally be home. However I soon learned that something really strange had happened to New York while I was away.

The Upper West Side, once the heroin capital of New York, junkies everywhere, menacing gangs, the Guardian angels, in my absence had gone from pit bulls to poodles. The Upper West Side is probably one of the most extreme examples of gentrification outside of the Meat Packing District. The graffiti on the walls I remembered was gone, and the trains were clean as a whistle. Although it got more upscale, my friends who remained did not. Some were tossed out of their homes as rent went up dramatically, once the land lords saw an opportunity.

Just as in Palestine, New York had been occupied by America. True New Yorkers had been displaced and shipped off to somewhere (I suspected Newark.)

For them, maybe it was like watching grass grow, but for me it was a shock to the system. I roamed around in a daze, high off of fragments of memories that could have been one or a collection of several mixed up into one. Time was completely off.

Many years later, in 1994, I had finished my first album and had release several 12″s under the name Sub Dub. Feeling a little unsure of my next step I decided to go back to my old neighborhood to soak it in and reflect.

I walked around the natural history museum, remembering when I was a kid my friends and I had stopped up all of the toilets with paper towels, flooding the 1st floor of the museum, then got caught and our pictures were taken, never allowed back in.

From there I went back to my old block. My elementary school had been literally cut in half to make space for a condominium. I found a concrete table that was fixed into the ground outside the school yard and looked down.

Wow, it was still there under several other tags written with a fat marker. Scribe. NSB/Non Stop Bombers.

I felt that old rush I used to get when I’d smell the chemicals of the aerosol paint or opaque markers. I pulled out a sharpie and crossed the letters out, then thought for a minute and wrote over it with a brand new tag name. Badawi.

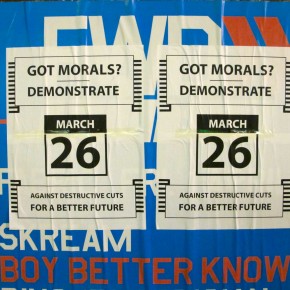

Photograph courtesy of papalars. Published under a Creative Commons license.

such a good article. very engaging