Woody Guthrie’s two greatest gifts were the deceptive simplicity of his songwriting and his unshakable devotion to sharing the power of music with everybody. The first chorus on New Multitudes, the latest collection of his songs, is remarkable for just how exquisitely it captures and frames both of them. And their mutually beneficial relationship: “Music is the language of the mind that travels. It carries the key to the laws of time and space.”

If you can get to the end of the “Hoping Machine” without being gripped by that line, maybe music isn’t for you. Woody Guthrie certainly isn’t.

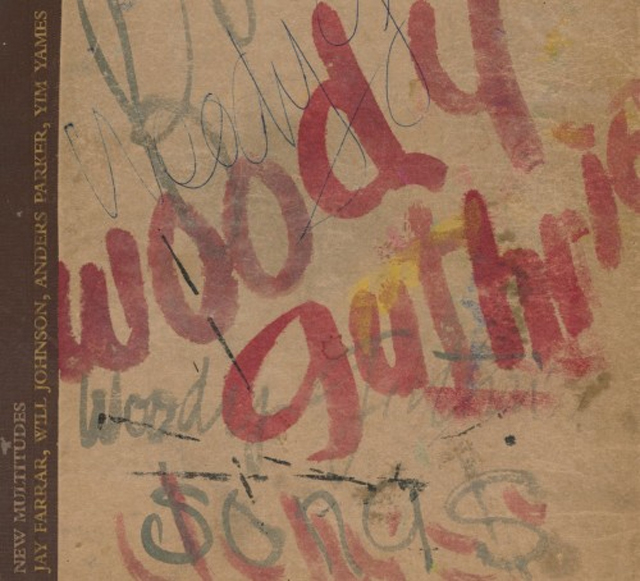

The latest batch of previously unheard Guthrie lyrics come to life via the hands of Jay Farrar (Son Volt), Will Johnson (Centro-matic), Anders Parker (Varnaline), and Jim James (My Morning Jacket, credited here as Yim Yames) – like-minded collaborators who’ve long trodden the troubadour path that became so romanticized in the wake of Guthrie’s career.

This 2012 collection marks Guthrie’s centennial year, reverently introducing today’s listeners to more of the lyrics – both the profound and the simple – that Woody wrote but never recorded in his 55 years. The two Mermaid Avenue albums by Wilco and Billy Bragg released over a decade ago marked the first forays into the vast collection of unheard songs and New Multitudes in some ways returns to the same muse that guided those efforts.

But whereas Wilco and Bragg made thrilling first inroads into the archive as explorers, Farrar, Parker, James and Johnson clearly set out to record a collection that maintains consistency in theme and tone as if its songs were intended to sit together.

“Hoping Machine” might have turned into a talking blues song, unspooling itself in Woody’s seductive Okie drawl. But Farrar stretches his mournful croon over guitars that build to a jangly crescendo. “Whatever you do and wherever you go,” he sings, “don’t lose your grip on life and that means don’t let any earthly calamity knock your dreamer and your hoping machine out of order.”

Wonderfully affirmative advice, but it’s the word “machine” that stands out here. “THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS” is the famous quote that Woody put on his guitar, in both a small sticker and scrawled in big block letters over nearly half the body. Guthrie wasn’t being literal, of course, but did want to emphasize his instrument’s practical functionality. Following through on this logic, a “Hoping Machine” would be similarly utilitarian, hoping endlessly, steadily, predictably.

In a way, that’s what Guthrie’s archive does for us a whole. It gives us a near bottomless reservoir of potential new music, while also helping us reconnect with those suffering-filled decades from the middle of the twentieth century that are rapidly losing their living representatives in this era.

As each passing year pushed Woody Guthrie’s life further into the past, thousands of songs remained frozen in time, boxed but never recorded. But maybe they were just filed away until they were needed.

The title song “New Multitudes” is about the listeners, the followers, the masses who will side with Guthrie in the fight for peace, togetherness and love. It’s the call of the 99 percent. Someone who saw nearly everyone as neighbors and friends, Guthrie would have greeted the Occupy movement as a natural extension of his populist ideals. Indeed, his son Arlo and longtime friend Pete Seeger marched with and performed for the flagship New York gathering, while his granddaughter Sarah Lee and her husband Johnny Irion joined with Occupy Vermont.

In this moment especially it’s too bad Woody isn’t still around. For the pundits who questioned – either through delusion or ignorance – the purpose of the Occupy movement, he’d have given them their soundbite, a simple yet profound distillation of what it is the multitudes expect and deserve in a fair and just society.

But the term multitudes serves just as well to describe the yet unheard material. Or perhaps even the new multitudes of musicians who are slowly bringing those songs to life again. All of those suggestions come to bear during the course of the album.

The Guthrie Archives – with its many thousands of songs from throughout his life – ensures that Woody will remain as restless in spirit as he was in life. The careful and deliberate curation by his daughter Nora ensures that Woody’s influence will continue to widen because, centennial celebrations aside, it’s a tantalizing collection for contemporary artists to draw upon.

The Woody Guthrie Archives are America’s undiscovered songbook. It’s like a trove of unpublished photos, but with the added bonus that absent music, the songs are incomplete. Musicians like Farrar, Parker, James and Johnson – and Billy Bragg and Wilco before them and surely more still to come – get to create with Woody Guthrie. That cosmic connection is filled with possibility and mystery. And it allows for an unbounded diversity of artists to project their own dreams onto Guthrie’s words.

There’s no rulebook that says unpublished Guthrie lyrics must be set to a steadily strummed three chords. And while New Multitudes stays firmly in the Americana realm of its creators, that’s far from the only way to play Guthrie. The eclectic 2011 compilation Note of Hope, spearheaded by Grammy-winning bassist Rob Wasserman, pairs Woody’s lyrics just as easily with jazz, hip-hop and spoken word.

These are interpretations of Guthrie lyrics, undoubtedly different in a musical sense from how Woody himself would have played the songs and undoubtedly different from how another musician would approach the same written words. Those rare instances when musicians have overlapped on the same set of lyrics become a fascinating study in contrasts, and proof of the marvelously rich level of possibility contained in the Archives.

James’ New Multitudes rendition of “My Revolutionary Mind” is vastly different from Rage Against the Machine veteran Tom Morello’s take on the same lyrics, “Ease My Revolutionary Mind,” from Note of Hope. The song is Guthrie searching for the right balance in love: “I need a progressive woman, I need an awfully liberal woman. I need a socially conscious woman, to ease my revolutionary mind.” James’ vocals and the song’s pace are meditative, while Morello’s take is direct, bursting with energy. James delivers the thought process leading to realization, while Morello tackles the lyrics as a decisive call to action.

The dark and wicked humor of “VD City,” which Johnson delivers on New Multitudes with a gritty drawl over distorted electric guitar and harmonica blasts, has been circulating for 51 years in the form of an unreleased bootleg recording of Bob Dylan, pre-Greenwich Village, sounding even more like a Guthrie clone than he did on his 1962 Columbia Records debut. The directness with which Guthrie describes the “human wreckage” is startling for the era: “There’s a street named for every disease here, Syph Alley and Clap Avenue.” The barely 20-year-old Dylan makes it into a frat-boy type joke, while Johnson nails the regret-tinged rowdiness of a man torn down by his own mistakes.

New Multitudes might be missing some of the caustic energy that crept into Bragg’s Mermaid Avenue contributions, but it mines a different sort of melancholy in Guthrie’s lyrics. Woody was never shy in writing about his own shortcomings and failures – particularly in love – and that thread is strong on New Multitudes, a decision on the part of Farrar, et al., that makes this stand as the strongest album of unpublished Guthrie material. The four function as a solid band, sharing duties rather than simply switching back and forth.

An instinctual and impulsive songwriter, Guthrie wrote about what was on his mind – and like anybody else that wasn’t necessarily the same thing from day to day. Two different songs can say the opposite thing, just so long as it works. New Multitudes brilliantly illustrates this in the back-to-back juxtaposition of “No Fear” and “Changing World.” On the first, Johnson sings “I got no fear of life / I got no fear of death.” On the second, Parker sings “I’m afraid to live here friend / I’m afraid to die.” Though direct opposites, both lyrics fit beautifully in context and, in typical Guthrie style, are honest, direct and simple, conveying the immediacy of strong emotions.

Though musical projects delving into the Guthrie Archives haven’t been prolific, there’s enough evidence from the twin Mermaid Avenue discs, three songs from Sarah Lee Guthrie’s 2009 children’s album Go Waggaloo, Note of Hope and New Multitudes to reveal how much the intent behind song selection becomes crucial to the end result.

Musicians can go for breadth and eclecticism, or settle into a common theme. Woody’s songs weren’t simply divided into the two camps of political songs and love songs. There are travelogues, nature songs, goofy wordplay, children’s songs, apolitical topical songs – in short a spread as wide as music itself.

So many words came streaming out of Woody that revision was unnecessary; he’d simply just write another song. To “write a song a day” was one of his 1942 New Year’s resolutions – fittingly written as his “rulin’s” – and it’s not at all far-fetched to believe he came close to achieving that goal. Woody’s songwriting output is incredibly bountiful, as if to counter a lack of bounty elsewhere in his life: a lack of money growing up, a lack of stability in much of his family life, ultimately a lack of capability and years after the onset of his Huntington’s disease.

Songwriting was something Woody could control, perhaps the only thing he really could control once the helplessness of his condition set in. For someone who believed his whole life in the power of music, Woody absolutely harnessed that power as a way to rage against the inevitability of his decline. Fighting to keep himself whole, he just kept on writing, a model of stubborn perseverance and unbridled creativity.

Plenty will be made of Woody’s centennial year – indeed, plenty beyond the fantastic New Multitudes – but what’s most impressive about these celebrations is just how great a portion of his output remains yet unheard.

Feature image courtesy of New Multitudes project