The Sri Lankan government is expected to be taken to task at a session of the UN Human Rights Council currently underway in Geneva, over its failure to convincingly probe allegations of abuses committed in the final weeks of its bloody civil war. The US and Britain are expected to back a resolution due to be voted on this week decrying Colombo’s failure to demonstrate accountability for alleged war crimes.

As Archbishop Desmond Tutu and former Irish Taoiseach Mary Robinson, wrote last month: “The UN Human Rights Council has an opportunity and a duty to help Sri Lanka advance its own efforts on accountability and reconciliation… if nothing changes, the crimes that remain unaddressed will continue to haunt Sri Lanka’s people and could ignite violence once again.”

Such words ring true. But the threat of recrudescent violence is not the only reason why Colombo must face up to its past. Last year Navi Pillay, the United Nation’s High Commissioner for Human Rights, stated with reference to Sri Lanka: “addressing violations of international humanitarian or human rights law [are] not a matter of choice or policy; [they are] a duty under domestic and international law.”

There can be little doubt that Sri Lanka has attempted to side-foot their obligations in this regard. Refusing calls for an international investigation into alleged crimes committed by the army, no senior member of the government or military has been prosecuted for war-time offences.

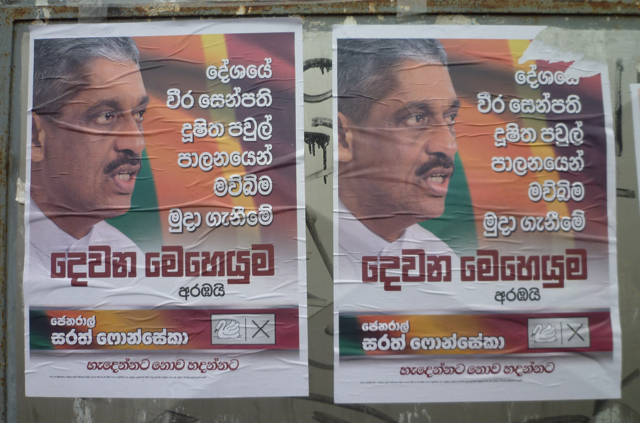

That is, except one. The former commander of the armed forces and rival Presidential candidate, Sarath Fonseka was last year imprisoned for accusing the government of extra-judicial killings ordered by the Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa. His allegations are supported by the accounts of at least two other members of the armed forces. Many see his detention as politically motivated, intended to simultaneously punish and silence him.

Whatever the case may be, it appears highly instructive that the only senior figure subject to the force of the Sri Lankan justice for his conduct in relation to the endgame of the war is a man known to be antagonistic to the political elite. This, in a country where journalists critical of the authorities have been murdered with apparent impunity, and members of the public challenging institutional power co-incidentally go missing with disturbing frequency.

Having won an electoral victory in 2010, pledging to protect his country’s “war heroes” from an international investigation, the President has consistently dismissed accusations of wrongdoing, maintaining famously that “not one civilian was shot dead” by the army. In response to international pressure, Colombo organised an internal probe that eventually produced the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission report, published last year. The findings of the paper, which made some significant headway in terms of addressing lesser war-related issues, avoided engaging with the deeper charges against the government and the military. These included possible offences against humanity and large-scale atrocities described as “credible” in a report produced by the United Nations last year, a conclusion also supported by human rights groups.

The most serious claims include the allegation that government forces shelled thousands of civilians to death on purpose and committed widespread extra-judicial killings, far from the eyes of international monitors. Many claim that there are thousands buried in the “no go” areas in the north where the denouement of the war occurred- inviting comparisons to the reported unmarked graves of Kashmir.

Recent announcements that a military court of inquiry would investigate allegations of misconduct connected to alleged abuses, ostensibly as a response to recommendations made by the LLRC, have merely crystallized an impression of ersatz justice being pursued by the accused institutions themselves, on terms comfortable to them.

Yet the dismal failure of the current political elite in Sri Lanka to convincingly examine itself is hardly surprising. To quote the wikileaks-released opinions of Patricia Butenis, the US ambassador to Colombo, in 2010: “There are no examples we know of a regime undertaking wholesale investigations of its own troops or senior officials for war crimes while that regime or government remained in power.” To which Ms. Butenis added, crucially: “In Sri Lanka this is further complicated by the fact that responsibility for many alleged crimes rests with the country’s senior civilian and military leadership.”

Now is the time for the UN human rights council to act decisively to put pressure on Sri Lanka to act in the best interests of its own people, by pressing its government for greater accountability, fixed to a standard set by the council. If Colombo fails to meet its obligations in such a scenario, a long-overdue independent investigation must be allowed to establish what really happened in the last days of the civil war.

It is obvious that accountability cannot be expected from the nation’s elite; more obvious still that until the ghosts of the war are laid to rest, this beautiful Island nation cannot move forward into the future it deserves.

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit