It was a golden opportunity. Four Jews had just been killed by a Muslim gunman. Accused of inciting ethnic conflict, the French President’s reelection campaign had been given the chance to repair the damage. All it had to do was recast the ex-Minister of the Interior as a tough cop who prioritized the security of the Jewish community.

They’d planned on kidnapping a Jewish judge. They were guilty of anti-Semitic preaching. Throughout the day, news anchors repeated the same statements, as images of heavily armed French policemen, rushing into darkened houses, ran across the TV screen. Suspects were paraded visibly handcuffed, their jackets pulled over their heads.

The second set of raids within a week, two weeks following the killings at a Jewish religious academy in Toulouse by a young Frenchman of Algerian background, the operation had begun. Islamic activists were being rounded up for questioning, and either prosecution, or emergency expulsion. Predictably, some were Algerian. Another was reported to be from Mali.

Nicolas Sarkozy was clearly making the most of it, providing a live commentary on the raids on French radio right as they were taking place. Despite being praised for his handling of the killings, France’s President had not benefited from them, as had been anticipated by the press. Polls were predicting a Socialist win, with up to 30% of voters estimated to be sitting out the elections. The economy was rumored to be more pressing. Sarkozy had to do something. He called on the security forces.

If you were Jewish, the message being broadcast was of direct consequence. You either felt reassured that the French government was proactively seeking out persons who had harmed your kin. Or, you assumed that this was an obvious bit of electioneering, aimed at restoring the confidence of law and order-minded voters, eighteen days before national elections. All the demographics were getting worked.

It was a classic Sarkozy conundrum, which, if he wins France’s elections, will stand as a testimony to his skill at bridging enormous political differences. Seeking out the support of Jews, on the one hand, and nationalists, on the other, is not an easy task. Some of those Jews will, ironically, be of North African origin. Most of the rightists will be, undoubtedly, anti-Arab white ethnics, the type of voters for whom little distinguishes Muslim from Jew.

Having conducted a reelection effort that has, in part, conflated the two, by advocating the banning of both kosher and halal meat products (slaughtered according to both Jewish and Muslim ritual proscription,) at the time of the Toulouse killings, Sarkozy was being accused of attacking one of his core groups of supporters in order to appeal to racists attracted to his competitor, Marine Le Pen. What better way to make up for this than staging a highly choreographed series of arrests of French Arabs.

The idea that Jewish voters will support a politician who persecuted Muslims is not new. American Jews are especially familiar with appeals to their fear of Islam, particularly in relation to the Arab-Israeli conflict. The belief that French Jews would respond to such outreach is belied by infrequent violence between the two communities, as evinced by what had just taken place in Toulouse. Some might argue that, in fact, Sarkozy was working a more justifiably anxious Jewish community than its American counterpart.

And yet, as though to underline the cynicism of his response to the Toulouse killings was his party’s singling out of kosher, in addition to halal foods, as threats to French cultural identity. Initially calling for the “labeling” of meats slaughtered according to Jewish and Islamic ritual proscriptions, Sarkozy was soon followed by Prime Minister François Fillon, who urged France’s Muslims and Jews to consider scrapping their dietary laws altogether.

Tying Sarkozy’s and Fillon’s attacks on halal and kashrut to the French right’s campaign against multiculturalism was Interior Minister Claude Guéant, who cautioned that awarding immigrants voting rights would result in Muslim majority city counsels imposing halal meat on school kitchens. “This is quite possible, given the proportion of foreigners in some areas,” Geant told France’s RTL radio.

Though some will argue that the scapegoating of Judeo-Muslim dietary laws was aimed at Arabs, Sarkozy’s decision to target Jews nonetheless introduced an element of anti-Semitism into his campaign that took many by surprise. The UMP’s effort also took a direct page from extremists, insofar as it succeeded in equating Jews with immigrants, by twinning Islamic and Jewish dietary laws, as being equally threatening and foreign.

This move was especially confounding considering the efforts made by populist parties to court Jewish voters in recent years, the National Front’s Marine Le Pen included. What was Sarkozy thinking? Predictably, it was all too consistent with the French President’s efforts to appear more rightwing than Le Pen, in order to draw away her most radical supporters. At the very least, it would help distance Sarkozy from his own immigrant and Jewish background (he is 1/4 Jewish, on his mother’s side) which ideally broadens his appeal.

For students of European populism, however, there is something instructive here. If Nicolas Sarkozy has made any ‘breakthrough’ in this campaign, it has been his explicit elision of anti-Semitism and Islamophobobia. It may have not have been intentional. It could very well have been a risk he had decided to take. However, he did it, and it has helped confirm what immigrants and activists have been saying for years, especially in Germany.

Islamophobia is not just an event unto itself, by itself, reflecting a fundamental discomfort with the Muslim religion, and the religious culture of immigrants from the Middle East. In post-Cold War Europe, it also functions as a substitute for anti-Semitism, and, simultaneously, as an incubator of that very same prejudice. It was only a matter of time before things came full circle, and someone thought it safe enough to mention Jews again.

That it was Nicolas Sarkozy who would be the one to let the cat out of the bag is entirely in keeping. Though he is not rabbinically ‘Jewish’, the French President has consistently leveraged his religious background for support, leaving open the possibility that he might just as well marginalize French Jewry if it suited him. It’s complex, for sure. However, it is highly reflective of Sarkozy’s own conflicts as a conservative of foreign background, who has consistently rationalized religion and ethnicity for political gain.

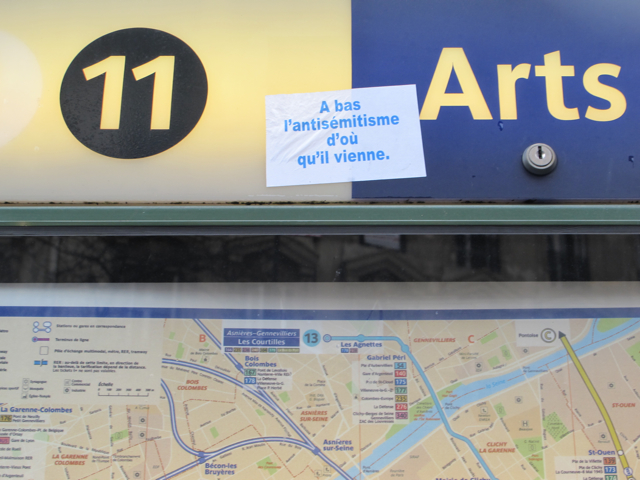

Photograph courtesy of the author. Joel Schalit discusses Nicolas Sarkozy at further length in Israel vs. Utopia.