Rock criticism’s great sensationalist Lester Bangs warned the world about the “Cybernetic Inevitable” that rock was fated to suffer. It was an evolutionary stage where flawless musical machines put human musicians out of work. “(W)hy not eliminate such genetic mistakes altogether, punch ‘Johnny B. Goode’ into a computer printout and let the machines do it in total passive acquiescence to the Cybernetic Inevitable?,” Bangs declared.

Such fears arose when he profiled Kraftwerk for Creem in 1975 after the German avant-electronic group released a robotically precise, Beach Boys-infected tune about the joys of driving on a West German expressway. Their synthesizers imitated the chugging of diesel engines on the speed limit-free highway while the Moog bassline had the rhythm of streetlights passing by. A monstrous, vocoder-distorted, android voice shouts the song title. Autobahn hit #11 on the UK Singles Chart and #25 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 chart. It was a time when synthesizers in rock were dominated by millionaire prog-rock stars who cranked out 1,000 notes a minute (“It’s not electronic music, it’s circus tricks on the synthesizer,” Kraftwerk’s Ralf Hutter carped about Rick Wakeman.)

Bangs was suspicious. He sensed there was a “Teutonic raillery” afoot and found that “Autobahn” was an “indictment of all those who would resist the bloodless iron will and order of the ineluctable dawn of the Machine Age.” Later in the profile, Hutter explained how his group’s bank of synthesizers and computerized gear “plays” the musicians whom then control the audience. “That’s what it’s all about,” he said. “When you play electronic music, you have the control of the imagination of the people in the room, and it can get to an extent where it’s almost physical.” Cue Bangs’ paranoia, and possibly that of countless Creem readers.

Little they knew about two albums that would encapsulate the “Machine Age” two years later.

“Let’s hear it for Frankie”

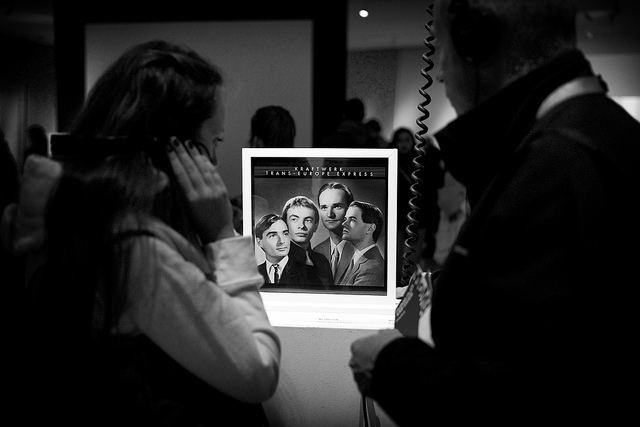

Thirty-five years have already passed since Kraftwerk released Trans-Europe Express and set the template for the next three decades of electronic dance music. The title track’s electro melody was famously sampled for Afrika Bambaataa’s groundbreaking 1982 Machine Age single, Planet Rock. It’s also the 35th anniversary of that album’s yang: the eponymous debut of NYC noise-rockers Suicide. Both were musically tapped in the Cybernetic Inevitable that Bangs feared. They achieved fine visceral impact in reducing melodies and rhythms to their cores, and locking them into mechanistic grooves that rarely paused. “We’d rather discover music as pictograms, very simple motives,” Kraftwerk percussionist Wolfgang Flur explained in a 2001 interview while mentioning a No Smoking sign. Nothing more than a few synth chords opens Trans-Europe Express where a percolating, Schubert-like melody glides across a simple, motorized beat in “Europe Endless.”

Likewise, many of Suicide’s songs stick to a three-note melody and a Morse Code-clicking beat. The punch is never compromised, namely in the funeral dirge of “Che,” where instrumentalist Martin Rev repeats a hymnal, one-chord riff while vocalist Alan Vega leads a congregation in prayer. Kraftwerk supposedly viewed the “man-machine” ethic as a means of achieving artistic perfection through their custom-built synthesizers, sequencers, and electronic drums. However, percussionist Karl Bartos later said in a Swedish television interview that they mimicked robots and “showroom dummies” as a pisstake in reaction to journalists’ claims their music was robotic.

Suicide’s early music was notoriously stifled by musical and technological limits (a cheap organ, a primitive drum machine often set on “Bossa Nova” or “Latin” presets, and a Roland echo effects box,) and they transcended them through Vega’s echo-drenched, Elvis-inspired vocals that arose from the dead. They caught the imaginations of rock critics, and countless European punks and industrial artists in their 1977 debut’s centerpiece, the 10-minute psychodrama, Frankie Teardrop. An unrelenting machine drone and a heart-pounding electro-beat set on auto-pilot form a genuinely cursed backdrop for an overworked, underpaid man who murders his family before descending to Hell. Vega drops the room temperature by 20 degrees in his screams a few minutes after telling the audience, “Let’s hear it for Frankie!” in a lounge lizard croon.

In his vivid history of New York’s music scene in the 1970s, Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, music journalist Will Hermes captured a peculiar moment at Suicide’s CBGB’s gig. He noted that Rev played a drum machine beat similar to William De Vaughn’s soul number, “Be Thankful for What You Got” before he delved into “Frankie Teardrop.” Vega then howled, “Shut the fuck up! It’s about you! You’re all Frankies!” If anything, Vega’s fury was a jailbreak from the Machine Age sound. Unlike the famously stiff-shouldered and unemotional live performances of Kraftwerk, Suicide sparked riots at concerts during the 70’s thanks to Vega’s Grand Guignol-style theatrics of assaulting audience members, self-mutilation, and chaining exit doors to punish naysayers. Young audiences ended up heralding them as elder statesmen of the NYC underground 20 years later. Vega was worried that Suicide’s days were over when he saw youngsters actually dancing to their music at a 2002 show in Edinburgh. “(They) had a disco ball going, I look out and people are fucking dancing to Suicide,” Vega lamented to The Wire’s Alan Licht. “I said, “Marty, I think we’re out of work,’ because we wanted the riots, we tried to inspire the riots.”

On appearances alone, Suicide and Kraftwerk came from different planets. Kraftwerk dropped their 60’s German counter-culture roots and resembled IBM executives (i.e. three-piece suits, $40 haircuts, Salesman of the Month-style portrait shots.) Suicide’s Vega and Rev typically clad themselves in cyberpunk drag by donning massive wraparound shades and Mod-like black leather jackets. In their early concert films, they appeared to be undertakers and fixed intimidating stares upon the repulsed or anxious audience members.

Kraftwerk and Suicide were both romanticists no matter how “inhuman” their music appeared to rock purists. The former gazed in awe of an idealized future while the latter often sought their teenage years in the Fifties as an escape. “I think that all artists are romantics, you have to be,” Vega said in a 2010 British television interview. “You’re the ultimate masochist to do what you do, you have to be romantic about it, you have to be in love with life or something to be that crazy to do the shit you’re doing.”

“There are noises around you all the time…that’s what makes my record”

Kraftwerk and Suicide nationalized raw electronic sounds in their 1977 albums. They translated many of the non-musical sounds around them into genuine sonic expressions. Synthesizer music was earlier the realm of studio experiments and novelty pop tunes. Kraftwerk romanticized the ambient noises of express train travel through West Germany’s industrial landscape, the namely the anvil hits heard when Trans-Europe Express seamlessly blends into the following track, “Metal on Metal.” My favorite moment in the title track comes after the chorus ends midway into the song and a humming synth drones emerges and then quickly disappears within a few seconds as if being a passing train.” Hutter and Flur stressed Kraftwerk’s pursuit of showcasing what they considered to be Germanness, particularly as an act of resistance against the dominance of American and British pop music in their country after World War Two.

Few American influences are heard in Trans. “The idea of Trans-Europe Express was to express our German identity, we wanted to incorporate the idea of Europe, and there’s a funk rhythm,” Bartos said in a television interview before chanting the deadpan chorus of “Trans.” Their radical approach was also a break from the kitschy results that came from electronic versions of classical music pieces, most painfully the ring-a-ding-ding camp of Wendy (nee Walter) Carlos Williams’ Switched-On Bach. Kraftwerk’s romanticized “German” sound of stiff funk rhythms and electro riffs wounded up being Americanized a few years later in Detroit thanks to the likes of Juan Atkins and A Number of Names. “Mad” Mike Banks of Detroit’s Underground Resistance collective argued that Kraftwerk’s touch transcended nationality and even humanity. “I’ve seen them play live many times but I’ve never heard anybody say anything about their race,” Banks, an African-American artist, told The Wire in 2007. “They weren’t Germans. They weren’t white. In fact, we thought they were robots. We had no idea they were human beings until we saw their show.”

Suicide fell in love with the din of traffic noise across America’s rotting highways and factories. The synth melodies of “Ghost Rider” and the hissing beats of “Rocket USA” Vega told Gonzai magazine in a recent interview about 24-hour drones he hears at his home near the Brooklyn Bridge. “It’s always there, you just don’t know about it,” he said. “Suddenly you hear it and go, ‘Holy shit!’ and then you realize it’s there all the time, 24/7, and there are other noises around you all the time…and that makes my record.” Such sounds are best heard in the sputtering, distorted synth riff of Ghost Rider and the B-side, I Remember, which was included in Mute’s 1998 reissue of Suicide. “Remember” particularly impacts my imagination through its feedback squeaks and concrete-grinding bassline that captures the constant bridge hum that Vega spoke of. “I remember how free we were/I remember incredible love,” he sings. Fifties Americana also saturated the shallow cultural myths that Suicide embraced, as expressed in the bare-boned rockabilly swing of Johnny and Girl. Vega would go on to score a French hit in 1980 through Elvis-influenced swagger of Jukebox Babe.

Much of Suicide’s lyrics deeply tapped into four centuries of American infatuation with the End Times – a hallmark of a world in a Machine Age where God’s machines reach their expiration and He cleans the slate for replacements. The selfish delight of watching sinners eternally wallowing in pain while The Faithful ascend to Heaven has energized many American imaginations and desires. Such pleasures were recently evident in the best-selling Left Behind novels and the thousands of believers who relinquished their wealth to join the flock of “prophet” Harold Camping who admitted last month that he has no idea when Christ’s Second Coming will be. The sensation of watching the modern world collapse during Judgement Day is a reoccurring theme in many noise albums, and Suicide imprinted a distinctly American aura in Rocket USA. Rev unleashes a hissing, motorized beat and a numbing, two-note keyboard melody while Vega drives a Chevy ’69 across a lone highway splattered by oil leaked from the wrecks of the damned while the Apocalypse is burning the sky. “It’s nineteen hundred and seventy-seven/The whole country’s doing a fix,” Vega croons. “It’s doomsday, it’s doomsday.”

Such a setting reminds me of a poem I studied in college that never left my mind. It’s “The Day of Doom,” a 1662 piece by Harvard-educated Puritan poet and preacher Michael Wigglesworth. He dedicated more than 25 stanzas to graphically detailing how adulterers, false Christians, un-baptized infants, and other sinners react to the Second Coming. “Mean men lament, great men do rent/their Robes, and tear their hair:/They do not spare their flesh to tear/through horrible despair./All Kindreds wails: all hearts do fail/horror the world doth fill/With weeping eyes, and loud out-cries/yet knows no how to kill,” Wigglesworth wrote. There’s a curious image that brings Vega’s speeding Chevy ’69 to mind. “Straightway appears (they see’t with tears)/the Son of God most dread;/Who with his Train comes on amain/to Judge both Quick and Dead” (italics mine). The Day of Doom or a Poetical Description of the Great and Last Judgement is considered to be the first bestselling book in colonial America and it became a staple of many Puritan households. Wigglesworth’s tragic, bizarre life could fit into a Suicide song – he was driven mad by his body’s series of nocturnal emissions and he later married a cousin since he felt too inferior to be with another woman. “He to his paradise is joyful come/And waits with joy to see his Day of Doom” was written in his epitaph.

“I used to give them the street back in their face, they come in to get entertained”

Kraftwerk’s fate was that their futuristic music ironically ended up being celebrated as a quaint, nostalgic artifact of the past. Many electro riffs from their 1981 album, Computer World were treated as “old-school” elements in numerous hip-hop and techno tracks. The group’s 1986 synth-pop hit, Electric Café also became the theme song for the Saturday Night Live parody of German postmoderism, Sprockets, and thus the stereotype of German artists being pretentious, humorless intellectuals was cemented. It’s difficult for me to listen to Trans-Europe Express with ears trained by so-called Intelligent Dance Music that came out of the late 90s; the simple synth melodies and beats now come across as sluggish and primitive. Suicide’s debut album relatively seems timeless – perhaps it’s how the music needs little more than two chords and an unhinged singer to hit the gut. The abrasive, wearied synth riff of “Ghost Rider” was recently sampled by Sri Lankan artist MIA.

In a peculiar coda, Bruce Springsteen, an exalted rock icon of Middle Americana, enjoyed Suicide’s first two albums so much that he covered “Dream Baby Dream” as an encore in his Devils and Dust tour of 2005. He also recorded the Suicide-influenced hallmark, Nebraska where tales of grotesque self-loathing and desperate attempts to chase freedom were captured on a cassette recorder in Springsteen’s living room. In a 2002 interview, Vega lamented about his inability to shock young audiences. “I used to give them the street back in their face, they come in to get entertained. We were just giving them the truth,” he told The Wire. “Now if you give them the street it doesn’t matter: the street is everywhere you go now, in reality. I couldn’t think of anything to do. If I killed somebody onstage: ‘Ah, what’s that?’”

Photograph courtesy of yoerk. Published under a Creative Commons license.