Forty-five years ago today, Egyptian President Gamel Abdel Nasser made the fateful decision to close the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping. This was the act of provocation that convinced Israel to go to war, although it would be some days before the actual decision was taken.

It is not merely because of that anniversary that I bring this event up. It has lessons that very much bear on the situation today, ones that Israelis, Americans, Arabs and Iranians should all learn.

After skirmishes with Syria had put the region in a heightened state of tension some months before, political pressures on Nasser, from his own population as well as from other Arab leaders, most notably King Hussein of Jordan, grew steadily. The monarch was expected to lead the opposition to Israel and he was looking very weak in that regard.

At the same time, Israel’s political leadership, led by Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, was facing increasing pressure from the military leadership and the political opposition, led by Moshe Dayan, to act more strongly in defense of the state for fear that Egypt would seize the initiative and lead Syria and Jordan into a multi-pronged attack on Israel.

As time went on, Nasser’s public speeches became more and more belligerent, including threats to obliterate Israel. Hussein charged that Israel was pushing for a war that would enable them to capture the West Bank. The Syrian Ba’ath leadership was dedicated to confrontation and was the most active to that point, engaging Israeli forces from time to time and also lobbing shells at Israeli towns near the Golan Heights.

Israel, for its part, insisted it wanted to maintain the peace, and Eshkol’s only goal was the continuation of the status quo. But Israel’s military leadership was uncomfortable with that stance, and the Chief of Staff, Yitzhak Rabin, had threatened to occupy Damascus and overthrow the Syrian regime. This caused alarm in the Arab world and reproach in Israel, where the public stance had always been that Israel did not have ambitions of expanding its territory.

After Nasser had demanded the evacuation of the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) from the Sinai Peninsula and deployed troops there, the pressure toward war had risen. Yet, Nasser, who had surprised Israel with the troop deployment, still had one third of his forces bogged down in a prolonged conflict in Yemen. He did not want a war with Israel at that point, but badgering from Jordan and the real risk that either the Syrians or Israelis would escalate their conflict and force Egypt to act thrust the decision upon him.

Nasser hoped that these moves would assuage Jordan’s view that Egypt was hiding behind the UN, would forestall escalating Syrian action and would deter Israel from an attack on Syria. And it might have done just that, but Nasser overplayed his hand by closing the Straits of Tiran. This was a violation of basic international shipping agreements and was viewed as very serious not only by Israel but also by the West. Even the USSR thought this was going too far.

Even then, the United States held to its position that Israel must not initiate hostilities, and the USSR, for its part, was quite stern in its warnings to Israel. But this was a direct threat to Israel’s policy of deterrence; in Israeli eyes, if Egypt could close the Straits without fear of consequences from Israel, then their military deterrent was gone. Thus, this step was the casus belli and the last straw against which the moderates, including the Prime Minister, could not stand.

Nasser took this step because the first two he took, which need not have necessarily led to war, ended up increasing the pressure on him, in part because it raised the level of Israeli anxiety, and as a result, its own tough stances.

In the end, both Nasser and Eshkol ended up in a war neither of them wanted because the political pressures built upon the moves each man made and pulled their nations inexorably in that direction. It was true for Hussein as well, who knew that entering the war was a foolish move, and who Eshkol contacted directly to plead with him to stay out. But if he had, Jordan, which was already viewed with animosity and skepticism in the Arab world, would have been permanently branded a traitor state. So he went in, too.

The superpowers also contributed to the march to war. The USSR especially, which sent Nasser a false report of Israeli troops massing on the Syrian border (they did this in response to a large call-up of Israeli reservists, which the Russians knew was not an immediate prelude to an attack, but to which they wanted Nasser to respond forcefully,) played a significant role. By the time the Kremlin changed its course and tried to restrain Nasser, they were unable to do so in the face of the overwhelming domestic and regional pressures Nasser was under.

The US, meanwhile, shared with the Israelis their assessment that if Egypt attacked Israel, the Israelis would dispatch Nasser’s armies with little problem. Though the Johnson Administration never actually gave Israel a green light for a pre-emptive attack, they eased their hold on the reins with which they were initially restraining Israel, and Israel knew from this that it could act without angering the White House.

We live with the results of these decisions to this day. The Arab-Israeli conflict was forever transformed and made immeasurably more difficult to resolve in the wake of the war. Israeli triumphalism and Arab humiliation have since combined to create a political atmosphere where Israel has had increasingly less reason to compromise and Arab leaders have found their options increasingly diminished.

While the Six Day War is seen by one side as a colonial war of expansion that Israel planned for some time, and by others a desperate fight for survival that was necessary to avert Israel’s destruction, it was neither of these. It was, in fact, a war that neither of the top leaders wanted, but which bad decisions, politics and brinkmanship made inevitable.

So what does this teach for today?

I thought of these events as I read of Israeli leaders expressing their skepticism about the talks that resume today between Western states and Iran over the ongoing nuclear tensions.

For over a decade, as both an activist, and a journalist, I have been reassuring people that the incredibly foolish notion of an attack on Iran is just so much loose talk. Hoiwever, in the past year, the volume of that talk has been raised to an extent that risks just the sort of chain of events that led to war in 1967.

Just in recent days, we have Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu saying that the only standard Israel would accept is the full suspension of uranium enrichment, the removal of all enriched material and the dismantling of the nuclear facility at Qom. Netanyahu knows full well that this is unattainable. He also adds fuel to the fire by saying that Iran is a “serial violator” of agreements.

Yet, less publicly, Israeli officials acknowledge they are talking tougher than they really can afford or need to be, and they are quite willing to accept much less than what Bibi outlined.

On the other side, Maj. Gen. Hassan Firouzabadi of Iran allegedly said, “The Iranian nation is standing for its cause and that is the full annihilation of Israel.” Thus far, I have heard no claims that Firouzabadi was misquoted, as Iran’s belligerent president, Mahmoud Ahmedenijad so famously was years ago, the effects of which we still feel today.

Congress’ passage of a bill that absolutely opposes containing a nuclear Iran and pushes the President toward a war is another step that makes the situation more unstable. And these are similar to events that have built one on top of another for many months now.

The talks today seem a likely indicator that the Western nations are committed to resolving this situation without an attack. This would seem to be in Iran’s best interest as well. And Israel seems to be acting in a manner that suggests they know that is the direction in which the wind is blowing, and it doesn’t seem likely to change.

If the bluster and brinksmanship can be kept in abeyance, this crisis may well pass without the cataclysmic results that an attack on Iran would cause. Hopefully, the events of late May and June of 1967 can provide a lesson for these leaders who are more concerned about proving how tough they are, especially in election years, than what is truly in the best interests of their countries and the world.

Like Eshkol and Nasser, it seems that President Obama and Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khameinei do not want war. Hopefully, they will be more successful than the last pair at avoiding the sort of political boulder rolling down a hill that leads to a war that serves no one’s interests.

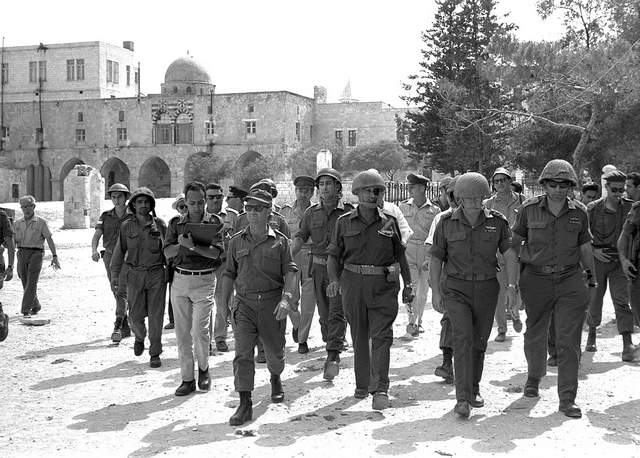

Photographs courtesy of the Israeli Government Press Office and Patrick Peccatte. Published under a Creative Commons license.

I think President Obama would do well to cut the umbilical cord that ties US foreign policy to Tel Aviv.

Morton, I daresay Obama would agree. As would many US politicians and certainly many diplomats.. The question is how?

M K Bhadrakumar noted that today’s date for the talks was chosen anything but randomly by the Iranians:

“May 23 is a memorable day in the folklore of the Iranian revolution. That was the day the tide of the war with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq turned exactly 30 years ago in 1982 when Iran’s revolutionary forces “liberated” the port city of Khorramshahr and registered their first victory on the battlefield.

Khorramshahr is etched deep in the Iranian people’s psyche. Therefore, when a prominent Iranian legislator pointed this out during an open session of the Iranian parliament on Sunday, he was invoking the archetypal symbol of resistance, honor and victory.” (“Iran nuclear talks gaining traction”, http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Middle_East/NE22Ak01.html)

He also writes about how France’s new president and the escalating Euro crisis have de facto tranquilized Europe in these talks.

On the other hand, then there’s also renewed Iranian infighting between the factions of Khamenei and always vitriolic Ahmadinejad, and while the latter (allegedly a fan of the messianic Hojjatieh Society, on top of it) may be increasingly sidelined, his words undoubtedly continue to reverberate within Iranian society & apparatus. (eg “Iran nuclear talks primed for failure”, http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Middle_East/NE16Ak02.html)