“How are we going to control one million Arabs?” That was the question posed by Israeli Prime Minister Levi Eshkol almost exactly 45 years ago, when Israel captured the West Bank from Jordan. It never seemed to occur to anyone, as they scrambled to come up with an answer they never really found, just how disturbing that question really is.

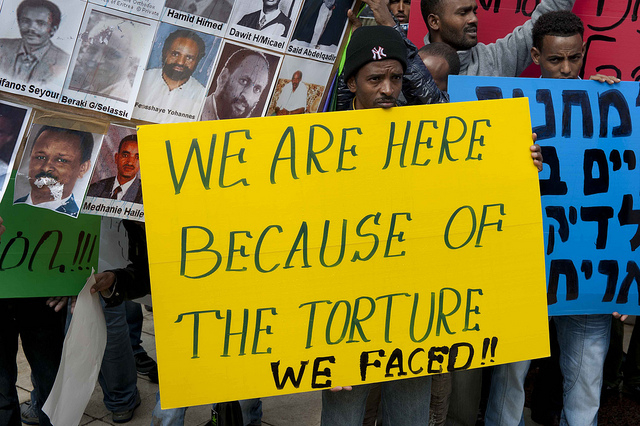

The result of that ethnocentric attitude has been manifest in Israel ever since. A stark reminder of its effect was delivered in an outpouring of hate against African refugees in Tel Aviv a few days ago.

The occupation of the West Bank has often been called “accidental,” most notably by Gershom Gorenberg in his book by that very name. And indeed it was.

Israel did not enter the 1967 war in order to capture territory, a fact confirmed by the records of the day and conclusively demonstrated by Avi Shlaim in an essay in the new anthology, The 1967 Arab-Israeli War: Origins and Consequences, which Shlaim himself co-edited. But as the decisive Israeli victory became clear, more and more land was taken. For Israel, the problem was the many inconvenient people that came along with it.

Those Palestinians were seen as a problem to be managed, not a responsibility Israel was taking on. That attitude has pervaded the occupation and become entrenched over the 45 years in which Israel has systematically denied the rights of Palestinians under their rule, further disenfranchising them above and beyond the tragedy that had befallen them in 1948.

In both the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, the Palestinians were already living under occupation, even when those territories were ruled by Jordan and Egypt, respectively. But be that as it may, the denial of basic rights to Palestinians under occupation cannot endure for four and a half decades without dehumanizing the population under occupation.

The pyrrhic victory that Israel won in 1967 had a great many effects. It cemented Israel’s military superiority in the region. It dealt a crushing blow to secular, pan-Arab nationalism and propelled the shift toward religious nationalism in the region. It transformed a cozy relationship between Israel and the United States into the “special relationship” that endures to this day. It destroyed Gamal Abdel Nasser, who had been Israel’s leading foe for fifteen years. And it brought East Jerusalem, especially the Old City, into Israel’s possession.

It also brought to Israel a triumphalism that bred great hubris and led the country into arrogant mistakes in ignoring Egyptian responses in 1973, rejecting a potential peace deal with Egypt in 1971, and misadventures in Lebanon on 1977 and 1982. It revived the territorial ambitions of “Greater Israel.” It birthed the modern settlement movement and radicalized religious Zionism into utter fanaticism.

It also came a year after Israel had finally lifted martial law from its own Arab population and had made serious strides in transforming its laws to treat the Arab minority as citizens. Even if land ownership and other benefits were tied to military service or the Jewish National Fund in order to keep the Arab population as a permanent “second class” in Israeli society.

Indeed, even the beginning of the occupation could not stop the momentum inside Israel towards addressing the civil rights of its Arab citizenry. That trend would grow through the 1990s, before it was eventually derailed, and subsequently reversed by the Al-Aksa Intifada and the collapse of the Oslo process – a collapse that still has not been recognized in Jerusalem, Washington, or even Ramallah.

But that newfound attempt to integrate the Palestinians who remained inside Israel was ameliorated by the introduction of a million more Palestinians who would not be given any rights of citizenship. Any overarching trend toward normalizing relations between Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs was undermined. This liberal sentiment was now placed in constant tension with the realities of Israelis who were part of a relatively free and vital society controlling the lives of Palestinians who enjoyed no civil rights, which were denied as a matter of course.

As the 21st century dawned, and the occupation was well into its fourth decade, the worst violence between Israelis and Palestinians since 1948 sharpened the ethnic tensions between them as well. More Palestinians were convinced that Israelis would never allow them to be free, while many Israeli Jews who had supported the peace process believed (thanks to the dissembling, political cynicism and foolishness of all three of the leaders of the major players at the time — Ehud Barak, Bill Clinton and Yasir Arafat) that the Palestinians were not interested in their own state but would only be satisfied with the destruction of Israel.

This is the most fertile ground imaginable for xenophobia. In today’s Israel, we can add economic stratification, thanks to years of neoliberal policies imported from the United States and Great Britain. Then we throw in the fact that Israel, with the most open and diverse economy in the region by far, is naturally going to attract those who flee their own countries, and we have a perfect recipe for the hatred that boiled over in Tel Aviv this past week.

The events in the Hatikva neighborhood in South Tel Aviv (an ironic name for a poor neighborhood; “hatikva” means “the hope”) are hardly unique to Israel, of course. The crowds were composed of the working class of Israel (the majority of whom are Mizrahim, Jews of Middle Eastern descent, Ethiopian Jews and other, non-European groups,) a class which is increasingly struggling to make ends meet and which sees its own position as being threatened by Sudanese and Eritrean refugees. These Israelis have watched their social safety net fray and tear, and their leaders make sure to keep that fact separate in their constituents’ minds from the massive amounts of shekels that are poured into the settlements.

In keeping with their xenophobic rhetoric, demagogic leaders of mainstream political parties incite against the migrants, using false crime statistics in order to scapegoat the Africans, calling them a “cancer.” This is just an Israeli version of a pattern of racial hatred that is very familiar to Europeans. Maybe this is why, in surveying foreign press analyses of the violence, there is so little shock about what transpired. Perhaps the outside world has finally stopped wondering how Jews, with our dramatic history of persecution, can act in such a “contrary” manner.

The road that led here began with ethnic tensions, and, yes, with a Jewish cultural mistrust of non-Jews, which has certainly been merited historically. But this particularly Israeli strain of racism has been nurtured by the occupation. Because only by hating, fearing and dehumanizing “the other” can people tolerate holding so many innocents under a regime that denies them their most basic rights. And when you can hate one group, you can hate any other. Indeed, this may very well be the ultimate legacy of the 1967 war. The logic, it appears, is inescapable.

Demonstrating migrants photograph courtesy of Physicians for Human Rights-Israel. Miri Regev photo courtesy of Israel’s Government Press Office. Published under a Creative Commons license.

I refuse to accept the notion that the six day war was accidental and that Israel “accidentally” conquered the territories. There may have been no plan (Israelis are known for improvising, not planning) but the conquest of the entire historic Palestine was in the very DNA of Zionism (Uri Avnery agrees). There is a reason Israel never declared its borders following its independence (something which it refuses to do to this day). As proof: only months after the 1967 conquest, Israel started building settlements in the occupied territories. There is no need for a “master plan” in order to prove that something happened by design. Hitler had no plan for extermination of Jews and has never issued such order, yet nobody claims that Jews were not exterminated. Plan Dalet was merely a plan for “securing” Palestinian villages, rather than expulsion, but that doesn’t mean that Palestinians were not expelled. To prove: by preventing their return, it proves both intention and plan. A serial killer may not plan every one of his murders but that doesn’t mean the murders didn’t take place or were not premeditated.

In the same vein, Israeli politicians didn’t order the pogroms of African refugees, but both they and the rioters are a direct result of the “Jewish State” DNA and blueprint. Israel is no different than what the US would have been under the presidency of David Duke and a ruling party of White Nationalists. When you teach people of a certain group, whether Aryan or Jewish or Christian Protestant, that the state “belongs to them” exclusively, these attitudes and incidents are inevitable. Not to mention the Apartheid and the occupation which are a result of the same ideology of exclusivity and supremacism.

Everyone who supports the notion of a “Jewish State” in a way is responsible. And it will only get worse.

“Perhaps the outside world has finally stopped wondering how Jews, with our dramatic history of persecution, can act in such a “contrary” manner.”

That perspective was part of the problem, whether framed in a philo- or anti-Semitic fashion. Jews share the same desires and frailties of the human species. If Zionism did anything, it forced the non-Jewish world to recognize this. We are neither angels or devils. The entire argument that a people who have been brutalized historically are unable to be brutal themselves is anti-human. Anti-human in that it is against human nature.

Don’t get me wrong, these horrendous acts must be condemned. Further, people should be arrested for their crimes against property and people. But remember, these were not “settlers”, hardeim, or the other groups the left prefers to condemn committing these acts. They were members of the urban proletariat.

Which brings me to my final comment. What Israel needs is *more* neoliberalism and openness in the economy. There is far too much crony capitalism and not enough of a real free-market. It also needs serious reforms of its political system (in particular cutting the influence of parties unable to gather more than 5% of the vote).