Calling Owen Hatherley’s A New Kind of Bleak a book about architecture is like saying Orwell’s Animal Farm is a book about a farm. Yes, it’s about Hatherley’s travels through the United Kingdom, in which he analyzes edifices ranging from the National Space Centre in Leicester, (affectionately called “The Maggot,”) to Preston’s bus station. However, it’s also about gathering the evidence necessary to indict British urban planning.

Owen Hatherley repeatedly reminds us that what a municipality chooses to dedicate urban space to reflect what the municipality values. For example, in the final chapter on London, he contrasts the 1970s tower Guy’s Hospital with the city’s new, tallest skyscraper – the Shard, which is intended to include high-end offices, luxury flats, a hotel and a spa. “The notion that London could erect a block of council housing or an NHS hospital as one of the pivotal objects on its skyline is now unthinkable,” he concludes. It’s not at all a stretch to see the Shard’s towering nature as symbolic of luxury’s paramount status in London, a city that Hatherley characterizes as “Old Corruption in braced glass, the satanic site at the heart of the UK’s malaise.”

Too often, renovating buildings and reinvigorating neighborhoods means expelling the people who already live there to make way for the offices, luxury flats and shopping areas to come. Hatherley gives us numerous examples of what, as he says, “all starts to look like a deliberate plan – space is freed up in the inner city, and new space is allocated in the exurbs. Crossrail will get the cleaners back in from Essex, and get the bankers from Maidenhead to Canning Town.” It’s a problem that’s by no means limited to London. Relatively the same could be said for New York City, where rent keeps getting higher in gentrified areas outside – but relatively close to – Manhattan, forcing people who can’t afford the prices to move further and further away.

Hatherley doesn’t present the alternative – rich and poor living side-by-side in parallel universes – as any rosier, either. He points out that the cities that erupted in the August 2011 riots – London, Manchester/Salford, Liverpool, Birmingham, Bristol and Nottingham – “by and large have the rich next to the poor, £1,000,000 Georgian terraces next to estates with some of the deepest poverty in the EU,” with that same principle leading to poor being ‘pepper-potted’ with stockbrokers in Housing Association schemes. “All of us, all along, if we were honest for a microsecond, knew this was a ludicrous way to build a city, to live in a city … I’d often idly wonder when the riots would come,” he writes.

When the riots occurred in England and Wales last year, Hatherley was in Scotland, where he was regularly reminded of the absence of rioting there. As a possible explanation for the lack of civil unrest, he offers the possible explanation of Scottish cities’ localization of extreme poverty in distant settlements. However, as Hatherley acknowledges, Glasgow and Edinburgh both have mixed districts, including Edinburgh’s Old Town, which he says “proves to be a surprising example” of such a district and where, incidentally, I lived as a postgraduate student at the University of Edinburgh. If a mix of residents living side-by-side in parallel universes is a recipe for disaster, then the chain of cause and effect does not seem to apply in all locations or in all circumstances.

A New Kind of Bleak doesn’t focus entirely on bleakness. Hatherley finds bright spots in the urban areas that he surveys – bright spots that could, and should, serve as examples for improvement elsewhere. One of those bright spots is in Aberdeen. There, “the money went somewhere decent, for once, in the renovation and upkeep of its housing estates – the one time I’ve ever really seen the boom’s capital evidently invested in the maintenance and respect, rather than the clearance and demonization of a working class area,” he writes. He finds another bright spot in the Ladywood area of Birmingham. The Chamberlain Gardens estate there is, for British council housing, “remarkably well-preserved, calm and attractive,” with a five-minute walk to the city center, according to Hatherley. That leads him to ask, “Why wasn’t it all like this? Why can’t it be done again?”

Hatherley is surprised to find one of the brightest spots in London – specifically at the Golden Lane Estate, where working class people “plainly manage to live well next door to architects who are paying through the nose for the same flats.” As such, Golden Lane is one of the few places in the UK that he says “really shows how we can create alternatives, how we can create a new, better and more egalitarian city.” However, to transform existing cities into more egalitarian versions of themselves, it will take the “intervention of the state, of planning, of the division of labour, of technology and industry,” according to Hatherley. That’s the crux of the book. In writing A New Kind of Bleak, Hatherley is attempting to make the form of coexistence that he sees at Golden Lane the norm for urban life rather than the anomaly.

It’s a vision for equality, at least in housing, that is of course also applicable in cities outside the UK. A New Kind of Bleak hits shelves in the US on July 31.

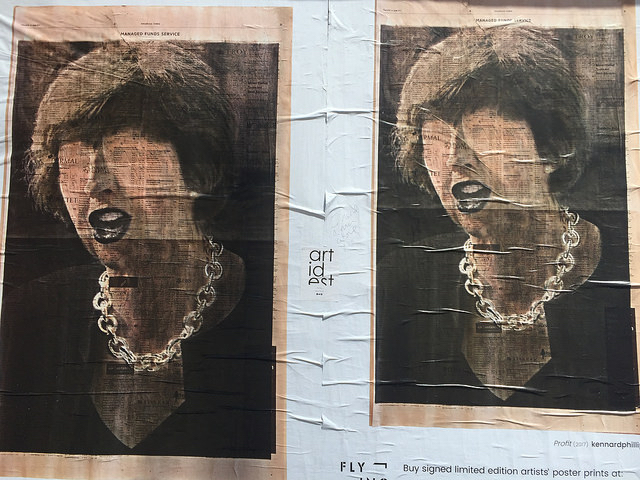

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit