Susan Sontag created Susan Sontag. The first volume of her journals and notebooks, Reborn, made that clear. As her son and the journals’ editor David Rieff writes, the entries show a young person who “self-consciously and determinedly went about creating the self she wanted to be.” The recently published second volume, As Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh, reinforces the notion that she – and, by extension, we – can consciously create our identities, or at least personas. However, the two volumes also show that, no matter how much Sontag created her ideal self, she, like us all, faced limits to how much she could change.

The two volumes cover very different periods of Sontag’s life. The first consists of entries from 1947 to 1963, roughly ages 14 to 30, a time in which she studied at the undergraduate and postgraduate level, got married, had her first and only child, got divorced, lived in two continents and wrote her first novel. The second volume, documenting 1964 to 1980, shows her entries from ages 31 to 47, a period in which she published her best-known works, became an icon and battled cancer. It’s easy to feel like an underachiever in comparison to Sontag’s professional success.

This success – and moreover, the freedoms and abilities that it brought – in many ways represents the accomplishments of goals that Sontag set in her earlier journals. “I want to write – I want to live in an intellectual atmosphere – I want to live in a cultural center where I can hear a great deal of music – and this and much more,” she writes in a February 1949 entry, after arriving at the University of California, Berkeley, at age 16. She, of course, went on to be a prolific writer, live in several cultural centers and counted some of the twentieth century’s most renowned intellectuals, writers and artists among her friends.

Despite her successes, she never stopped trying to transform herself into the person that she wanted to be. Sontag never felt that she “had made it,” that it was okay to stop becoming and just be. At age 24, her list of things to do (and not do) included showering every other night (a “do”) and not publicly criticizing anyone at Harvard. Twenty years later, her list of rules included getting up in the morning no later than eight and writing in the notebook every day, using Georg Lichtenberg’s Waste Books as a model. She also remained a forever student – as Rieff writes, her success, if anything, made her more of a student, rather than less.

As part of her autodidactic program, Sontag’s journals and notebooks were primarily a place where she worked through ideas, some of which went on to become the ones that made famous. These notes on literature, film, philosophy and culture are valuable in themselves and make the journals worth reading, even if someone has no interest in other aspects of Sontag’s life.

However, what the journals accomplish most is humanizing Sontag. For better or worse, they show a side to her not found in her essays or novels – a Susan Sontag that had her heart broken time and time again, who was plagued by insecurities, including a fear of being alone. As Sontag wrote in one 1970 entry, while in another unstable love affair, “If I’m not safe in the deepest relationship, I can’t really give my attention to other things too. I’m always turning my head back, to look anxiously if the other person is still there.”

It’s Sontag’s most emotional entries, which usually focus on difficult or failed relationships, that differ most from the pieces that she published during her lifetime. In that sense, some of the most profound elements of Sontag’s journals are not her thoughts on the books she read, the films she saw and the politics she observed. The reader already has at least some grasp of her ideas on these topics from her published works and interviews. What matters most about the journals is that they show Susan Sontag the human being, not the Susan Sontag, the persona that she fashioned for the world to see.

For that reason, as much as the journals are about Sontag creating her ideal self, they are also about the parts that she could not change. No matter what Sontag accomplished professionally, how many people admired her and how many she books she read, she did not stop fearing being alone, loving people who did not love her back and always feeling that she was a work in progress. At least not as of 1980, when the second volume of her journals ends. We can only wait and see what unfolds in the final volume.

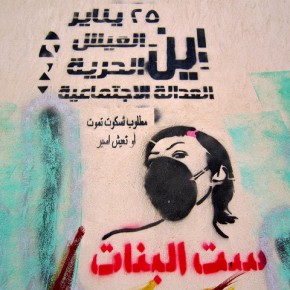

Photograph from Sarajevo courtesy of Anosmia. Published under a Creative Commons license.