Michelle Fawcett, co-organizer of Occupy the Film Festival said people had asked about the title of the event. Did she mean “Occupy: The Film Festival” suggesting a festival about the Occupy movement, a completely suitable topic for a program taking place in the weekend leading up to S17, the first anniversary of the birth of Occupy Wall Street (OWS)? Or, did she mean, “Occupy the Film Festival”? That is, in addition to the numerous other occupations (Occupy the Hood, Occupy Research, Occupy Our Homes etc.) it was time to occupy that institution — the film festival — which once a showcase for artistry potentially lost in the shadow of Hollywood, had become a marketplace and an event deeply tied to commerce and the tourist industry, even in its commitment to art. She liked the confusion, because for her, the answer was both. The absence of the colon added a key ambiguity that opened up potential for this event to house multiple meanings, not unlike OWS itself.

To be fair, not every film festival is tied to the production of markets and consumers. Many are dedicated to producing public space for marginalized communities and to cultivating advocacy networks and capacity building (membership and fundraising.) [Shameless promotion alert: Many of these festivals and ideas are covered in the collection Film Festivals and Activism, which I edited with Dina Iordanova, which includes scholarly pieces alongside contributions from festival programmers, activists, and filmmakers.] This fact was not unnoticed by the programmers, who enjoyed the participation of a member of the Human Rights Watch International Film Festival team.

That said, this was very much a grassroots effort reliant on collective effort and goodwill. The site of the festival speaks volumes; the Anthology Film Archives was born from a collective effort to cultivate an appreciation of cinema through an occupation of continuous screenings. It is a center for preservation and screening today, in particular focused on protecting and showcasing the independent and experimental work—the cinema “created outside the commercial mainstream.” Organizations known for their work in media and social change came on as partners to assist, offering outlets for publicity in exchange for promotional space in the festival. These include Paper Tiger Television, Deep Dish TV , Cinema Libre Studio, MAG-Net: Media Action Grassroots Network (a project of the Center for Media Justice) People’s Production House and Haymarket Books as well as Queers for Economic Justice. Further aiding the no-budget festival were unpaid volunteers (including friends from the NYC Grassroots Media Coalition, who collected in person and online to help curate and organize the event.

To call this no-budget is not entirely accurate, not only in light of those donating time, effort, and materials that cost. It may be worth keeping this in mind, because as much as many fantasize about creating “pure” spaces fully free from commercial presence that is not always possible. Very rarely, if we consider the presence of smart phones, browsers, video hosts, social media, computers and other technologies that ensure our on-going immersion in a corporate world. But this did come close, and anyway, purity restrictions rarely lead anywhere good.

The programmers sought to avoid protest porn, those images of protesters violently clashing with police that frequent mainstream media reportage and YouTube. (As much as we might wish online to be a site of utopic collectivity, practices of online voting often ensure hierarchies of interest that are sometimes disappointingly in line with dominant—and destructive—perspectives.) The goal here was to reflect on the Occupy movement, to look at what had been done, to consider where it stood now, and where it could go. This was crucial in light of the one-year anniversary reports that seemed keen to declare that the movement had lost all momentum. This was a time for taking stock, and regrouping, literally and figuratively as events were bringing people back to occupy public space throughout New York City.

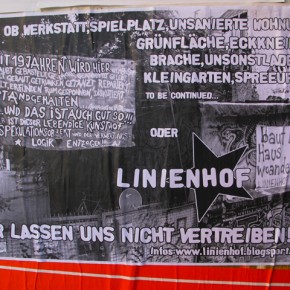

Occupation of space began not inside the theatre but in the upper lobby. Indeed, a film festival is more than its film program: it is a live event that involves the physical collection of people who encounter the screen, each other, and additional materials. In this way, media are connected to the social in a visceral and material way, with real life and real space physically altered for at least a weekend. The walls were papered with posters from the Occuprint Collective recalling OWS and the general strike of 1 May—a holiday (Mayday) that, in my lifetime and experience, has not been so publically or popularly acknowledged in America.

Four other exhibits brought other material mediations of the movement, crucially reminding visitors that smaller analogue media also played a role. One table carried a display of Occupied newspapers from across the U.S. The striking assemblage contradicted claims of the death or growing irrelevance of print journalism: on the ground it appeared to thrive as a means of counter reportage and connecting the occupiers of each city to their collective time and space. More importantly, these publications persisted, even as encampments faded. (To be an academic about it, I am tempted to point out Benedict Anderson’s assertion that newspapers were crucial in the construction of national collectives, or what he called “imagined communities”.) Across from this table, a handful of panels displayed the work of two photographers. Vanessa Bahmani’s black and white portraits, entitled “We are the 99%” showed people holding signs explaining their situation and how they can to be part of Occupy while Andrew Stern’s color photographs showed instances of Occupy across the nation, including protests from Occupy the Hood and home foreclosure defense actions.

Encompassing the entire space, in a manner, was The Illuminator, described by the programmers as “a tactical media machine (aka a van with a really powerful projector, sound system, and library) that has been roaming the streets of New York City and beyond, bringing the spirit and message of the Occupy movement to street corners and public squares everywhere.” Specifically: it projects words and images against buildings and sky and other public space as a means of redesigning the landscape and calling people to action. This spectacle is part of a larger mobile projection venture, which is presently seeking donations via Kickstarter.

These displays were significant not only for their reminder of the role of media in social change—a useful point of entry for this film festival—but also for something they all shared: An almost joyous merger of old and new media, a vibrant assembly of digital and analogue. Bahmani’s “We are the 99%” recalled the We are the 99% Tumblr, where people uploaded their testimonies using the same trope: Figures holding pieces of paper or cardboard on which they wrote their stories. The digital haunted these portraits done on film using a medium format camera. The point Bahamani said, was to slow things down when posing, to encourage the participants to sit and reflect. One of Stern’s photographs showed a flyer from 596 Acres, a New York-based organization which identifies vacant space—a resource that vastly outsizes the number of those in need. The paper leaflet is affixed to a chain link fence but on the leaflet is the image of a QR code, suggesting the possibility for further engagement—after this encounter—through mobile phone and internet technology. Both movement and media spread in Occupy, rendering previous borders and structures porous. These are changing the structure of lived and mediated space.

The program carried on these themes, and more: The films built on the intermediality (the entwined connections of media formations that rely on, refer to, and give meaning to one another) that characterized the entry and further developed networks with considerations of the movement historically and internationally. The festival promo produced by MK12 united these themes in a short that began with what looked to be a game of Pong. One side wins disproportionately, growing into a massive wall; it is only with the collection of additional players on the other side that they can begin to combat the inequality of the game. The camera pulls back to reveal more ‘players’—the lo-fi bars who, from a distance become like twinkling LEDs in a global map.

The world has come together, and is shown to do so in an aesthetic that recalls earlier electronic media, its primitive aspect conferring nostalgia whilst uniting old media with new. The Revolution Will Be Televised, promised Livia Santos’s documentary chronicling the movement in California and New York. Meanwhile, Angeline Gragasin’s playful PSA Occupy: Citizen Journalist Super Suit showed how a person might prepare for the role of citizen journalist with instructions on dress, neutralization of pepper spray, and the best way to document action on one’s camera. An appreciated touch was the reminder to shoot horizontally on one’s camera phone. Not only is the vertical mode distracting, but a proper aspect ratio will travel better across other media platforms.

The first in a two-part series. Part two can be read here. Screenshot from American Autumn courtesy of Occupy the Film Festival. Published under a Creative Commons license.