One of the first things I did when I arrived in Germany as an exchange student in 1986 was to walk into a bookstore and buy a collection of Bertolt Brecht’s plays. I spoke almost no German. And the only Brecht I had been aware of back in the states was his libretto for the Kurt Weill “song-play” The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, which I had watched with my opera-mad father on a Metropolitan Opera telecast.

But something inside me longed for the experience of Brecht’s language. Somehow, I knew how it would sound before I knew how to sound it out. Stranger still, I intuitively grasped the extent to which his politically charged approach would estrange the conversational German I’d spend my year abroad learning.

My lovely language instructor at the month-long boot camp I attended in a tony Hamburg suburb — never before or since have I had such a crush on a teacher — was shocked at my temerity. How could someone who couldn’t even conjugate the verb “to be” without assistance hope to learn anything productive by laboriously translating Brecht’s clipped, idiom-rich German in linear sequence?

After initially trying to dissuade me, though, she came to realize that I would only learn if my heart was in my work. Once, I ran into her on the street outside of class and she graciously consented to walk fifteen blocks with me talking about her life and asking about mine.

As a suburban American who had been both sheltered and shunned in high school, I was politically naïve by any European standard. But I wanted to be a leftist badly enough that I was rapidly able to discern that inclination in the people I met. Without having to ask, I soon determined that my teacher was a socialist and, more improbably, that she respected my quixotic effort to become one through my DIY form of extreme cultural immersion.

Throughout the rest of my language course, she let me work on my translating at a desk set off from the rest of the room while my overprivileged and underserious classmates made her miserable. Periodically, she would come over to help me with particularly difficult phrases. Although I frequently felt like my brain was going to explode, I was in heaven.

When I wasn’t in class, I used my free time to wander around Hamburg looking for the Germany I was desperate to find, the place where radicalism wasn’t just a private college dormitory fantasy, but part of the fabric of everyday life. I scoured working-class neighborhoods like Altona and the red-light district of St. Pauli for evidence of down-to-earth leftist politics. Even though I couldn’t understand most of the flyers and posters I came across, I could usually tell from a few key words and their iconography when they reflected the sensibilities I was so eager to cultivate in myself.

Towards the end of my month in the city, my temporary host brother, a “Young Socialist” who was always having heated debates with his middle-of-the-road father, excitedly asked me to join him on a service mission in one of Hamburg’s grimiest quarters. Naturally, I jumped at the chance.

That’s how I found myself carrying heavy furniture up three flights of hard-to-navigate stairs for a family of Middle Eastern origin that spoke almost as little German as I did. Once they realized I was an American, they gave me strange looks. But our shared plight as inarticulate outsiders — and, I’m sure, appreciation for my hard work — gradually established a silent bond forged through eye contact and smiles.

By the time the move was over, I was exhausted and exhilarated in equal measure. It was so nice to have finally had an opportunity to do something in keeping with my political yearnings, especially since it didn’t involve speaking or writing. When my temporary host brother insisted that we reward ourselves with a trip to a classic working-class Hamburg pub for a thick soup and glasses of bitter Jever pilsener, it felt like I had finally arrived in the Germany of my dreams.

As will no doubt be obvious to people less deluded than I was an impressionable teenager, the rest of my year abroad made it painfully clear that the Germany of my dreams — or the one of my temporary host brother, for that matter — was not going to be that easy to make real.

And indeed, over a quarter century later, the country is still torn between its deep-seated conservative tendencies and the impulse to give traditional leftist politics a multicultural turn. Progress has been made, in places, but often with the palpable threat of backlash looming nearby. Germany today feels like a country waiting for its moment, but afraid of what it might bring.

In the course of helping to curate the photographs my Co-Editor-in-Chief Joel Schalit has been taking in Berlin for the past few years, I have often been struck by this sense that, for all of the massive changes that have come to Germany since I was an exchange student there — the fall of the Wall, reunification, the development and subsequent crises of the Euro as a currency — public political discourse on the Left has barely budged.

The same causes, the same slogans, even the same designs pop up over and over in the flyers and posters that paper the “blank” surfaces of the urban landscape. Since I usually agree with the spirit of the rhetoric, if not its particulars, I do not find this sense of déjà-vu all that discouraging.

But I do wonder sometimes, just as I did when walking around Berkeley in the 1990s, whether that might not be a better way of communicating the Left’s key points than by methods perfected when Hitler was beginning his rise to power.

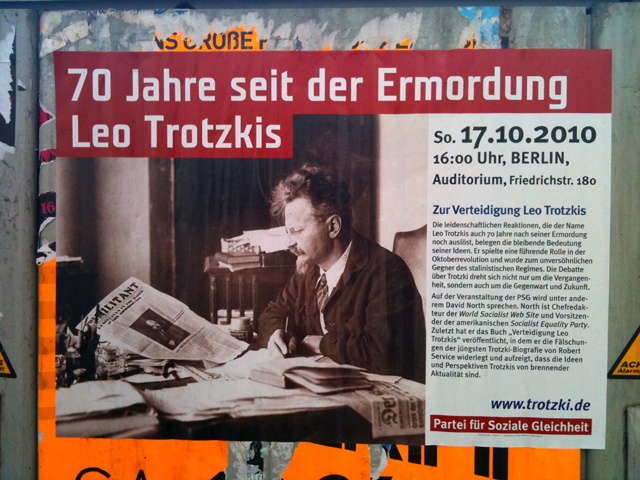

Take this poster for an event commemorating the seventieth anniversary of Leon Trotsky’s assassination in Mexico City, photographed back in 2010. It’s hard to argue with the man’s historical importance. Yet the insistence on hearkening back to his example, at a time when some of the most pressing concerns for the Left are very difficult to express in terms of his political themes, strikes me as a self-marginalizing gesture.

That said, the part of me who thrilled in the summer of 1986 to find evidence that German radicalism had not died out under Helmut Kohl’s stolid leadership is still swayed a bit by the unapologetic invocation of leftist tradition in this poster and others like it. Here’s the text:

70 Years Since the Murder of Leon Trotsky

Sunday, October 17th, 2010

4pm, Berlin

Auditorium, 180 Friedrichstraße

In Defense of Leon Trotsky

The passionate reactions that the name Leon Trotsky still elicits 70 years after his murder, attests to the continuing significance of his ideas. He played a leading role in the October Revolution and became an implacable opponent of the Stalinist regime. The debate about Trosky turns not only on the past, but also the present and future.

Among others, David North will speak at the Party for Social Equality’s event. North is the principal editor of the World Socialist Web Site and Chairman of the American Socialist Equality Party. Most recently, he has published the book In Defense of Leon Trotsky, in which he refutes the falsehoods in the latest biography of Trotsky by Robert Service and demonstrates, that the ideas and perspectives of Trotsky are of a burning contemporary relevance.

www.trotzki.de

Party for Social Equality

Commentary and translation from the German by Charlie Bertsch. Photographed in Berlin by Joel Schalit.

The Party for Social Equality (PSG) has recently threatened another Trotskyist group with taking them to court for violating the PSG’s property rights by planning to show a film on which the PSG claims copyright.