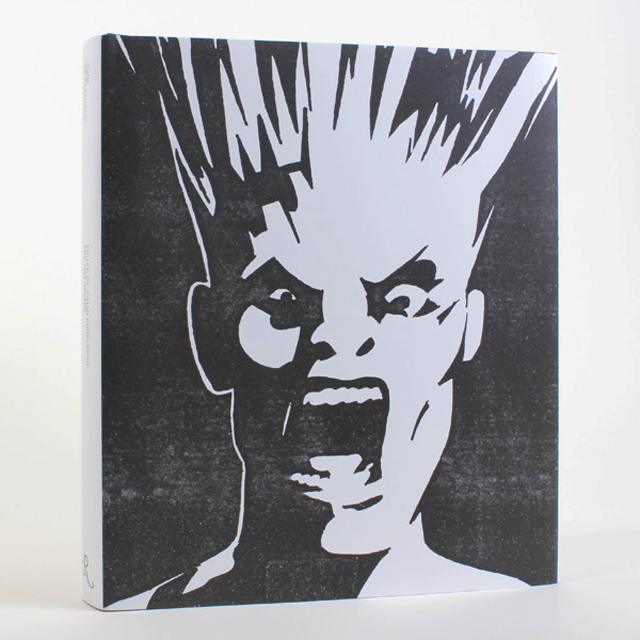

The back cover and spine of Punk: An Aesthetic are almost entirely white, with a clean, black typeface. Seen from a distance on a bookshelf, it could be any modern art book. But the front cover — punk cartoonist Gary Panter’s illustration of the singer for The Screamers — is another matter, a large, low-quality print of a black-and-white face fixed in what looks like a scream of rage, befitting the book’s innards.

Look inside and you’ll see a riot of images: hand-scrawled political rants, shredded clothing, swastikas, pornography, violent photomontage and hundreds of others from the 1970s punk movement. That screaming face on the front cover gives you the feeling the content inside doesn’t want to be contained.

Indeed, when editors Johan Kugelberg and Jon Savage took on the task of assembling a visual narrative of the punk aesthetic, they found it to be a difficult thing to capture, both logistically, because of the media’s fleeting nature, and conceptually, because of its oppositional, apocalyptic impulse.

“Cultural negation isn’t self-documenting,” Kugelberg notes.

As a result, there’s a good deal of debate in the accompanying analysis by the editors — along with contributors, novelist William Gibson and punk artists Gee Vaucher and Linder Sterling — as to whether there even is such a thing as a punk aesthetic, much less exactly what it is.

If does exist, it should be somewhere in these pages, or the dozens of boxes of artifacts that the editors amassed from public and private collections around the world. Pop culture writer Kugelberg joined Savage, the one-time zinester whose 1991 book England’s Dreaming is a touchstone for punk history, and created an exhaustive catalog of T-shirts, record covers, zines, handbills, posters, photos and other ephemera from the time. The curator at Cornell University Library, where most of the collection now resides, describes their work as having “advanced a better understanding of the cultural landscape of the late twentieth century.”

But the art surrounding punk, like the music, is slippery. It exists on shreds of cheap copy paper, images of other media it dragged into a garage, shredded, glued back together and immediately lost. And exactly what it meant varied greatly depending on the person it bounced off of before moving on to the next.

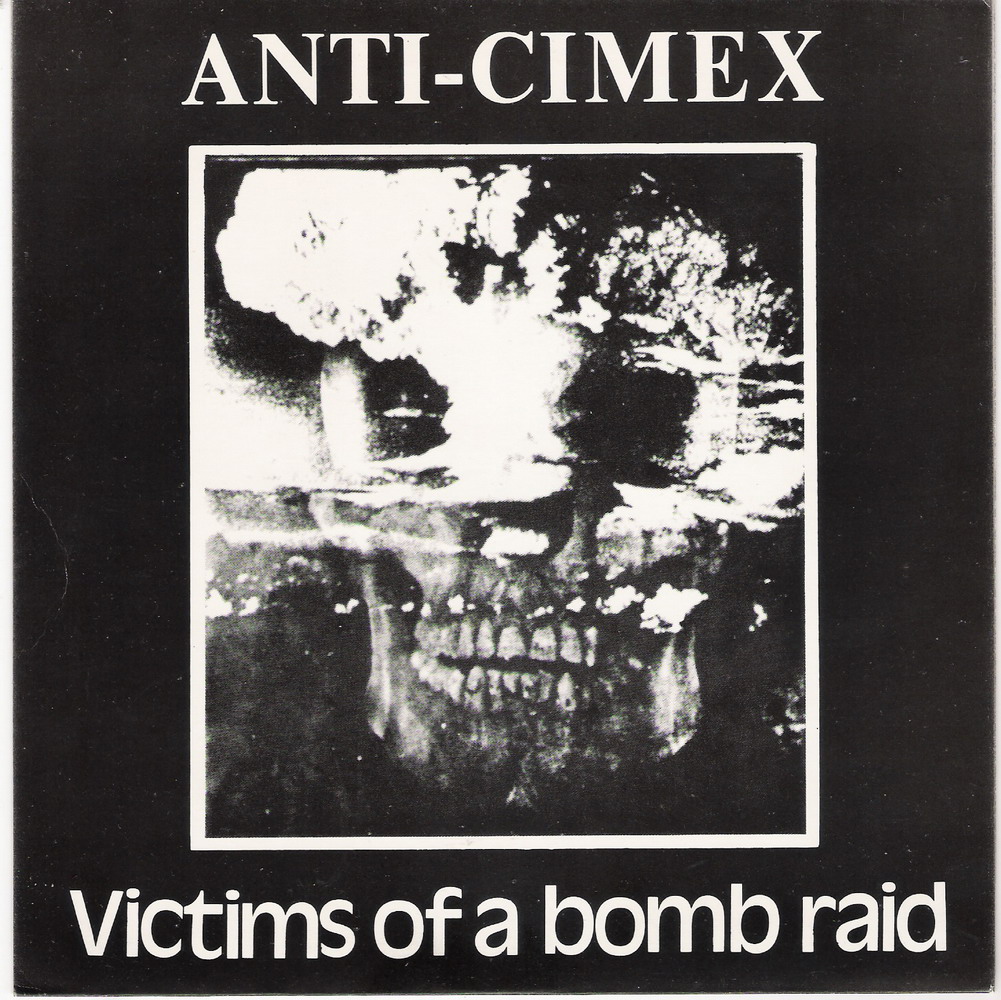

So the resulting collection is appropriately chaotic. It starts with raging Situationist flyers from the late 1960s and gay, glam and proto-punk zines, Debbie Harry at her platinum, dead-eyed best; then on into gig posters and photos from the early London and New York scenes. The centerpiece of the book covers the explosion of the Sex Pistols and Malcolm McLaren’s nihilistic fashioning of their image, followed by the adoring or outraged reactions from the rest of the world. It closes out by charting the splintering legacy into post-punk, hardcore, new wave and modern pop culture.

While the feat of the book is the compilation of images, the contributors provide some profound insights in a series of essays that attempt to make sense of it all, or at least concede there’s little sense to be made.

“The notion of what punk became as a signifier and yardstick remains a maze and a riddle, and amen to that. The history of the punk aesthetic cannot be told, only shown…” Kugelberg argues. And quoting The Simpsons:

Marge: The moral of the story is—“

Bart: “There is no moral to this story. It was just a bunch of stuff that happened.”

Part of the challenge in pinning down a punk aesthetic is that it inherently wasn’t a thing that wanted to be documented or codified, but rather a petulant opposition to such things. A counterculture to the Counterculture.

As Gibson puts it in his essay for the book, punk was the “cracks in the monolith of the baby boom 1960s.” He calls it his refuge from “the congealed fat in the cold griddle of Woodstock Nation.” Punk’s aesthetic didn’t care if it was recorded and it didn’t want to be defined, because it wasn’t building a new world like its hippie predecessors. It was destroying.

But in the book’s storm of incongruent images, something is there, something that persists. Kugelberg notes that you can see it in Banksy’s street art, graphic design, VICE magazine and, for better or worse, Hot Topic. Like pornography, you know the punk aesthetic when you see it.

For one, much of the art shares distaste for packaging or at least the appearance of packaging, from Suicide’s scribbled band name on flyers, to the zine Sniffin’ Glue’s masthead in handwritten marker. So much of the material collected in Punk: An Aesthetic looks, well, shitty.

But that’s because speed was the crucial factor in its creation. As Savage puts it, “One way to achieve this intensity of life was to be faster than everyone else. That’s how you avoided the dead hand of definition, commercialization, and reification.” The images were cheap, mass-produced on crappy early Xerox machines. This, he adds, “informed punk’s urgency, as it seemed like the image was on the point of disappearing.”

Another consistent thread through the collection is a sneering, unrepentant humor. Punk was “black, black, black” Savage reminds us, scary and mean. But it was also about not taking anything in life too seriously. This duality is one of the common threads that jump out. Whatever their dark connotations, the images were — more than anything else, maybe — funny.

That humor comes through in another recurring theme, which is the use of repurposed material. Forever fontified by the Sex Pistols, the ransom-note magazine clipping is everywhere. Entire zines were rebuilt from ripped up mainstream images. The artists behind them were ripping off shreds of the monolith and making them into something more interesting. Or to use Gibson’s other metaphor, grabbing a hunk of cold, congealed fat and lighting a fire under it again.

The photo collages by Savage, Sterling and Vaucher from the time are some of the best examples of this approach included in the book. Sterling replaced the heads or body parts of people with consumer objects, giving them a funny but eerie, zombie-like appearance. She would take images from women’s magazines and men’s pornography and mash them together, rebuilding gender roles in her own vision.

These recurring visual elements are a function of what the editors seem to agree is the true legacy of punk art, even if it’s not, strictly speaking, an aesthetic: the explosion of self-starter culture.

In describing her process, Sterling recalls, “Punk was the cutting out of the question, ‘Can I do this?’…the distance between having an idea and executing it was minimal.” It’s that speed and availability that made the aesthetic feel so different. It was about the present and the future, not the past. Sterling describes the moment of tension in her collage work, after making a scalpel cut, but before the “sticky permanence of the adhesive.”

That’s a fitting description of where punk lives.

So what happened once that glue dried? Did all the books on the meaning of punk force it to congeal? It has certainly had many deaths over the years, as each wave of revival played itself out.

Gibson suggests that maybe punk isn’t a cohesive aesthetic, but a code you recognize, or a “rolling ball of code.” It reaches people with something simple like a T-shirt seen on television, but grabs them as an irresistible emotional impulse, affecting and attracting everyone a little differently. That code is still around and strong, even if though those who operate under it now might look at the original punks and find them trite.

Kugelberg suggests that this evolving punk impulse is why it has managed to become commercial over the years but still continue on and retain a semblance of purity at the same time. The youth pick up the code and run with it, taking for granted where it came from.

As a result, new generations are able to have powerful and authentic punk experiences, he concludes, even if they are doing so based on inauthentic subject matter.

So the mini-movements keep fragmenting and exploding, faster and faster. The online anti-organization Anonymous comes to mind, evolving into something new every time someone starts to pin it down. It’s hard to imagine that the countless new versions of punk could ever be captured in a bound narrative history ever again. Then again, you could argue it’s not really contained in this one either.

Photograph courtesy of Rizzoli USA