2012 is just about done. A good deal has transpired in the Israel-Palestine conflict in this year, to put it mildly. In many ways, the events of the past twelve months have paved the way for significant developments in 2013. Let’s take a look at what some of those events might be.

Israel

2013 will get off to a fast start in Israel with new elections that promise to bring a government that is well to the right of even the current one. The joint Likud-Beiteinu ticket will win, and it is quite possible that Netanyahu, if he so chooses, can get not only the right-wing parties, but also some of the centrist ones into his governing coalition. Given the rightward tilt Likud took in its primaries and the link with Yisrael Beiteinu, including centrist parties could give Netanyahu an absolute mandate.

Labor leader Shelly Yachimovitch is non-committal about joining a Netanyahu-led government. She may be more tempted now that there is going to be an opening at the Foreign Ministry in the wake of Avigdor Lieberman’s resignation. But Labor would likely gain more by reclaiming the leadership of the opposition and re-establishing itself as the counter to Likud (a position the Kadima party occupied in the last few years) than by being Bibi’s junior partner. And aside from non-Zionist and Arab parties, only the tiny Meretz party would hold Labor’s left flank. That means the other key centrist parties aside from Labor, Yesh Atid and Ha’Tnuah (Yair Lapid’s and Tzipi Livni’s parties, respectively) would constitute what opposition there would be to Bibi’s left. That’s not much, and it certainly doesn’t represent an opportunity for any sort of serious change in Israel’s suicidal course.

The HaBayit HaYehudi (The Jewish Home) coalition with the National Union party has zoomed to the number three spot in polls, and is certain to be part of Netanyahu’s coalition. But, if Yesh Atid and Ha’Tnuah also join the government, Bibi will have the leverage he needs to both encompass most of Israel’s right, and at least try to present a somewhat more reasonable face to the rest of the world. Such an attempt would be transparently phony, but that hasn’t stopped such charades from being effective in the past. Indeed, it was, in part, Labor playing this role in governments headed by Ariel Sharon and Ehud Olmert that led to its demise over the past decade.

What this all adds up to is a right-wing coalition that could well be large and have a wide enough spectrum to encourage even bolder steps to destroy any possibility of a peace process. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, though, for the Palestinians or for people who work to see an end to this conflict.

The Israeli right, especially the secular right represented by Likud-Beiteinu, revels in defying world opinion. As one senior Likud source told Ha’aretz, global and even US condemnation of recent Israeli announcements of settlement expansion is “excellent − it is sheer profit for us.” With Yachimovitch courting the settler vote and reminding everyone that Labor is responsible for most of the settlements, the simple truth that Israel’s political mainstream is not interested in the sort of minimal compromises necessary for peace will become even more apparent.

It will also be clear that only outside pressure can possibly bring a resolution to this conflict, a resolution that will be even more imperative to Europe and the United States in the wake of changes in the Arab world. Is it possible that such pressure could manifest? The signals are mixed, and it certainly won’t happen in any significant way in 2013. However, there are some positive signs.

United States and Europe

At this point, we can rest assured that President Barack Obama is not going to stand up to the powerful political forces that oppose any move that might lead to resolving this conflict. AIPAC, CUFI and their fellow travelers are just too big a hassle when Obama, who is disinclined in general to get into tussles with powerful lobbies, has more pressing domestic concerns. And as long as the US continues to scuttle actions by the UN Security Council and provide billions in aid to Israel annually, it will continue to be a big part of the problem.

But there are some reasons to think things are changing, albeit at a glacial pace. As I recently wrote, Obama seems to be reacting to the Mideast quagmire by pulling as far away as he can without incurring the sort of political issues he is trying to avoid. He is also poised to appoint Chuck Hagel as his Secretary of Defense, a move which AIPAC, with the organized Jewish and Christian Zionist communities behind it, is opposing. While the outcome is by no means certain, at this point, this seems like a battle the vaunted Israel Lobby is going to lose. That offers a bit of promise for the beginning of Obama’s second term.

But the relative inaction of the US is meaningless if Europe doesn’t accept the signal that it is free to put more pressure on Israel, and their recent behavior does not indicate that they are taking the hint. Still, there is a clear sense of anger from EU diplomats. This is likely coming from a few sources: Netanyahu’s brazen attitude is grating on the Europeans, and it is making it harder to justify Europe’s ongoing inaction; popular opposition in Europe to Israeli policies is growing; and perhaps the biggest factor is a growing concern that the shifting political landscape in the region is going to make a resolution more imperative while Israel is making it impossible.

These conditions are all going to grow in 2013. Netanyahu is making it absolutely clear that condemnations, criticisms and displays of outrage are not going to slow him down. He will push the occupation envelope until there are reasons for him to stop. His right wing coalition will continue to push him down that path, and until Europe or, much less likely, the US actually provides some consequences for these actions, Bibi will keep taking the next step. 2013 may not see this dynamic reach its end, but it may well give us an indication where that end might be.

Palestinians

The Palestinians are ending 2012 in a very unusual position. Both Fatah and Hamas have seen victories against Israel, each in their own way and their own milieu. Hamas withstood an Israeli air assault and negotiated a cease-fire on better terms than had ever been approached before. Fatah led the push for the upgrade at the UN that so infuriated Israel. Each party, in the end, supported the other and the two victories were intertwined.

What might this mean for the Palestinian body politic? Maybe nothing, but maybe it helps provide part of the bridge needed for Palestinian political unity. Now that the PA has moved away, at least a little, from its role as Israel’s subcontractor, and Hamas, despite some bombastic statements, has continued to mature into a real political body, there may be more common ground for the two to come together.

This raises consternation for many in Jerusalem and Washington. Everyone knows that without Palestinian unity, there cannot be a resolution to the conflict through diplomacy of any kind. After all, with the split, any deal made with the PA excludes Hamas, by definition, and vice versa. Put simply, there is no more chance for negotiating peace with only one part of the Palestinian body politic than there would be for a peace negotiated only with Israel’s Labor Party.

The door opened by recent events is one where Fatah and Hamas can find a unity that does not negate either of their strategies. Fatah has come to be seen as weak and quisling, while Hamas is resolute and stands up to Israel. But Hamas has shown no real strategy toward an endgame, and many Palestinians realize that the religious party brings certain obvious drawbacks in dealing with the West and with Israel, not the least of which is their insistence that, even if they will agree and abide by a political agreement, they will not recognize Israel. Whether one agrees with that stance or not, it is obviously a diplomatic hurdle, one Fatah can overcome.

The two could come together and meld their methods and strategies. They can be two parties within the Palestinian movement, not unlike the way Labor and Revisionist Zionists existed before 1948. As tense as that relationship was at time, the combination obviously succeeded in creating the State of Israel. Fatah and Hamas would do well to emulate that example.

There will be other formative factors in 2013. The Iran issue has not gone away, and both Iran and Washington continue to show distaste for compromise. Egypt and Turkey are likely to move to strengthen their respective positions of leadership in the region, and this will certainly impact Israel-Palestine, especially if Turkey is serious about re-establishing ties with Israel. And Egypt’s revolution may be entering a whole new chapter after President Mohammed Morsi’s failed power grab. These are just two examples of factors that are likely to play big roles next year.

2013 could well be a decisive year in Middle East politics on many levels. Rarely has a year begun with so much potential for fundamental shifts. The Israel-Palestine conflict seems more insoluble than ever, but it has also never so much resembled a pressure cooker that might blow loud enough to force external action. Ironically, it is the very hopelessness of the situation that could keep some hope alive.

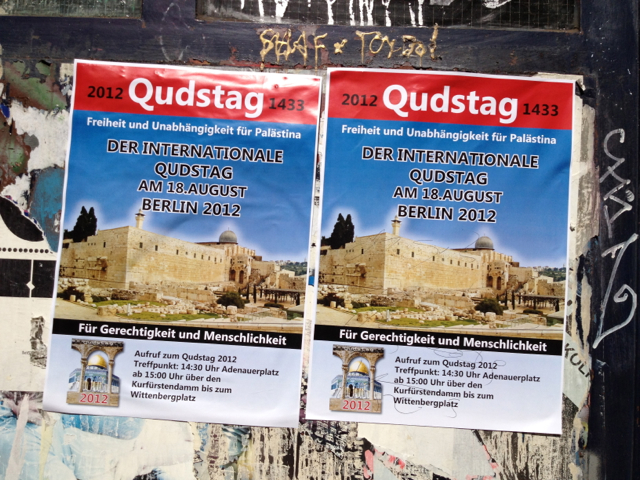

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit

In regard to Israel’s thumb-in-the-eye w.r.t. international law and international opinion (on settlements, occupation), the EU and South Africa have become a bit restless, as if reassessing the talk-but-never-act program which has been holy dogma since 1967 (or 1948) guaranteeing no movement toward compliance by Israel, and it is my sense (no one can prove such a thing) that Obama is encouraging this restlessness. Also, we might have a US SecDef who is less attuned to Israel (and to neocons) than over many years.

Throw that in the hopper with some pop-corn and watch 2013 unfold.