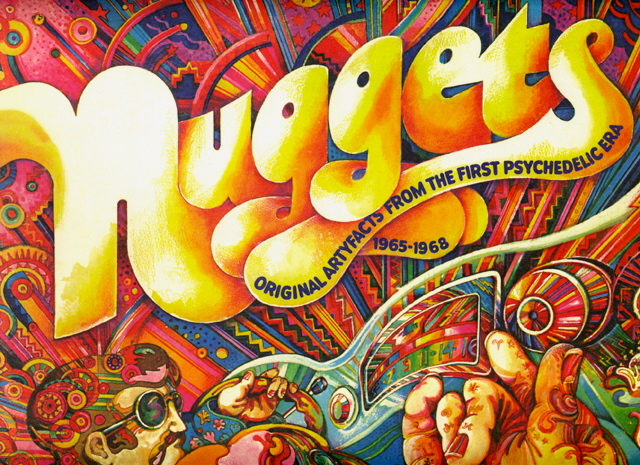

“Not again,” I thought, looking over the new releases on display at the record store. The top shelf featured a 40th-anniversary reissue of Nuggets, the classic garage compilation, while the one below offered a 45th-anniversary version of The Velvet Underground and Nico. It annoyed me that I was being asked to buy music I already owned. But this displeasure soon gave way to a more productive mindset.

Even if I didn’t enjoy feeling like a mark, it was nice to be reminded of something I love. I’ve bought most of the tracks on Nuggets more than once over the years. And I love the Velvet Underground’s debut so much that I needed to buy it a second time in 1996 when a compact disc reissue promised much improved sound and a third time in 2002 when a two-disc expanded edition offered both mono and stereo mixes. Not to mention that, despite usually steering clear of box sets, I had eagerly sprung for both the Velvet Underground box set and the 4-CD expansion of Nuggets that Rhino released in 1998, as well as its Europe-focused sequel.

More important than being reminded of my fannish devotion, though, was the fact that I was forced to think about these albums together for the first time. Although many of the songs on Nuggets date from the same period as The Velvet Underground and Nico, the latter’s ties to the Andy Warhol scene had led me to put it in a different mental compartment from other rough-hewn 1960s rock. But perhaps I’d been too hasty with my classifications.

In the end, this urge to reevaluate was strong enough that I ended up buying both reissues. Even if I’d already had most of the tracks at my disposal, it seemed important to scrutinize more closely the latest attempt to repackage them. At a time when the music industry depends more and more heavily on convincing people to pay for what they already have, the supplemental material that appears on a record has never been more important.

Like many of the expanded editions that have been coming out in recent years — usually in time for the holidays — the latest reissue of The Velvet Underground and Nico is available in more than one form. For the true completist, there is a six-disc 45th-anniversary box set that provides the original album in both mono and stereo versions, as well as an impressive array of rehearsal performances, songs the band ended up not releasing under their own name, and a show from 1966 which, despite being mired in acoustic sludge, is a remarkable document because it was recorded on the road, in Columbus, Ohio, far from the Factory scene.

But there’s also a more manageable two-disc version of the album that is in some ways a lot more interesting to ponder, since it is targeted at those consumers who might be willing to spend $25 on a classic album, but are hesitant to commit to the box set, whether for reasons of money or time. Actually, since the whole six-disc collection is available on Spotify, the latter is a more likely explanation.

The massive changes that file sharing has wrought on listening habits are no longer confined to those willing to risk illegal activity. Now it’s pretty easy for almost anyone with a modest income to pursue musical interests painlessly. But there has to be sufficient motivation to do so. Perhaps that explains the existence of the two-disc version of the 45th-anniversary edition. Its purpose could be to remind fans of the Velvet Underground who aren’t totally obsessed with the band — people like me, to be honest — how good their music can be, while also introducing new listeners to its pleasures.

It certainly worked that way in my case. While it is true that I rarely buy box sets and have almost never purchased one new — they can usually be had at a steep discount a year or two after being released — I was sufficiently captivated by the two-disc version to seek out the material on Spotify. Although I lacked the dedication to make note of all the differences between alternate versions of the tracks on the album, I enjoyed hearing them both as rough drafts and live. And the nearly thirty-minute-long conclusion to the concert, called “The Nothing Song,” gave me a much clearer sense of how the band might have appealed to the hallucinogen-minded demographic.

That rambling improvisation aside, however, I was struck by how much more “rootsy” the songs from The Velvet Underground and Nico sounded to me when I heard them in several different guises. It was almost as if the New York art world touches I’d been accustomed to focusing on had been canceled out in the act of comparing versions. Or maybe this impression was simply the result of the fact that I was hearing the history of the album’s gestation with the garage rock of Nuggets on my mind.

If the 45th-anniversary edition of The Velvet Underground and Nico is focused on giving a more complete sense of the album’s contents, adding more material to the historical record, the 40th-anniversary reissue of Nuggets takes the opposite approach, asserting the primacy of the original compilation over the four-disc 1998 box set and other collections released under the moniker. The sumptuously crafted 180-gram vinyl version makes it particularly clear that, even in an era when consumers can put together their own playlists with ease, not all compilations are created equal.

Reprising sentiments he first expressed for the 1998 box set, longtime Elektra Records boss Jac Holzman notes that, “This was no K-Tel bargain TV ragbag, but a serious study. I sensed that we were near a time when doctoral candidates would be writing dissertations on all aspects of rock.” In other words, his conception of the project, which he would ask Lenny Kaye to realize, was rooted in the conviction that the history of rock and roll had developed to the point where it demanded to be taken seriously. Or, to put this insight more bluntly, that rock and roll was history, with everything that double entendre implies.

“Nuggets was instant archeology,” Holzman writes, “where the dust had barely settled on the remains, yet we intended to excavate them and offer them to the public.” It is probably no accident that this wording conjures the image of a place like Pompeii, not left for later ages to discover, but turned into a tourist attraction in few short years. The album’s release “created an enormous stir,” he adds, “as much for its concept of an archeological dig into the recent past, as for its contents.”

This statement confirms something I already sensed when I first learned about Nuggets in the 1980s — at a time when the record was almost impossible for a suburban teenager like me to come by — namely that there was something deeply significant about its approach to history, the way its organizing principle dilated the span of a half decade until it felt like a century or two.

Although it would take me years to learn to think clearly about most cultural phenomena, I went to high school at a perfect time to develop the instinct to “always historicize.” DC-101, the mainstream rock station I listened to, played plenty of new material alongside classic rock stalwarts like Led Zeppelin and The Who. Rather than leading to sense of continuity, however, this juxtaposition emphasized how radically music making had changed since the early 1970s.

New songs, whether by Yes, Bruce Springsteen or Rush, almost always betrayed the influence of the era’s ubiquitous synthesizer, the Yamaha DX7, and the canned beats that always seemed to follow in its wake. No matter how well written, no matter how heartfelt, they still came across as somehow inauthentic, cut off from rock and roll’s foundation. By contrast, even the prog-rock excesses of bands like Emerson, Lake and Palmer and Genesis seemed vital.

But it was material from the Nuggets era that threw the sorry state of ’80s rock into sharpest relief. Like many stations at the time, DC-101 had started a “Psychedelic Hour” devoted primarily to material from the mid-1960s, before professionalism started to sand down its do-it-yourself lysergic edges. Desperate, like so many teenagers, to find a way out of the hellish “Just Say No” mentality that had been drilled into us since Ronald Reagan’s ascendancy, I relished this music’s lack of decorum, the way it made a point of crossing every line it could. The fact that I was unable to shop for it at my local record store only enhanced the appeal.

Indeed, despite that fact that the music industry was supposedly doing well back then, I remember the 1980s as a time of scarcity. Over and over, I would search for a record I’d read a lot about, only to find that it was out of print or only available as a high-priced import I didn’t understand how to order. I’m not just talking about the music of the one-hit-wonders who appear on Nuggets, either. I knew that bands like Big Star and The Velvet Underground were considered extremely influential, but had no clear sense of what they sounded like, because I never heard them on the radio.

Even when Lou Reed’s infamous Honda commercial pushed “Walk on the Wild Side” back into the spotlight, his work with Mo Tucker, Sterling Morrison, and John Cale remained decidedly underground, especially for those people, like me, who didn’t live within range of a good college radio station. Remarkably, it was not until my freshman year at UC Berkeley that I listened to The Velvet Underground for the first time, when a friend was playing their debut in her room at the notorious Barrington Co-op and I found myself transfixed by the slow build-up of “Heroin.”

Not coincidentally, that was also when I first got to hear some of the tracks from the original Nuggets. Rhino released a more mainstream compilation under that name in 1986, pairing Lenny Kaye’s better-known finds with “Wild Thing” and two songs by The Monkees. Although I knew that I was missing out on some great material — the Rhino album was also quite a bit shorter — I was too delighted to worry. Finally, I was able to flesh out the fantasies I’d had listening to DC-101’s “Psychedelic Hour.”

And that’s the connection between these two albums for me, the one that I’d missed in classifying them differently: they both sound hard to get. Whether the amateurish touches that define them were a function of necessity, as was surely the case with many ’60s garage rock releases, or calculated art, as was true of The Velvet Underground and Nico, to listen to these records is to marvel that their message wasn’t returned to sender. They make you feel very lucky to have found them.

I’ve indulged in these autobiographical details because they underscore just how much things have changed in the past few decades. Even as late as the mid-1990s, lessons in popular music history were likely to come through one’s social networks, with friends helping to fill in the gaps in each other’s collections. Now it’s often simply a matter of how much one cares to learn, since it’s not hard to find whatever musical evidence is required.

Although this state of affairs may sound attractive in theory, it does contribute to a kind of tunnel vision. People are led from one topic to another in the course of their internet searches, but the chain of associations that results tends to be highly idiosyncratic, lacking the depth imparted by contexts in which overarching structural relationships come to the fore. If I start looking up The Velvet Undergound, for example, it’s more likely that I’ll end up following a thread about John Cale or Sterling Morrison’s careers — or, for that matter, Andy Warhol’s — with concomitant detours into experimental drone music or medieval literature than that I’ll be thinking about their music’s proximity to other artists of their era.

In short, my experience in the record store of seeing the 45th-anniversary edition of The Velvet Underground and Nico right below the 40th-anniversary edition of Nuggets is difficult to replicate in the topography of an internet search. That kind of serendipity, along with its corollary in the brick-and-mortar bookstore, is becoming harder and harder to find these days. We may stumble upon all sorts of interesting things in our wanderings on Google, Wikipedia or Spotify, but the trajectory they trace is usually motivated internally, by what we already knew we wanted, rather than externally, by what we hadn’t ever thought to look for.

Perhaps this is a needlessly fine distinction. Happy accidents are still possible, no matter what leads you out the door. Yet I can’t help but wonder whether the reissue culture that these two records exemplify, with its endless repackaging of old material for new times, doesn’t reflect the troubling realization that we’re suffering from a scarcity of scarcity.

Our problem isn’t that nuggets are in danger of being buried so deep that we can’t find them again, but that they get lost amid so many other things deemed worth saving. As a consequence, we are understandably nostalgic for a time when, as Brian Eno reportedly said, “The first Velvet Underground album only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band” and when even accomplished rock bands were in danger of being utterly forgotten a few years after their last record came out; a time, in short, when mining for gold was an appropriate metaphor for the task of the critic, as opposed to today, when it would be more appropriate to bury it somewhere and throw away the treasure map.

Photograph courtesy of Rhino Records

Excellent piece! I loved the original Nuggets album when it came out, but was unmoved by the vast majority of sequels and spinoffs (hello, Pebbles) in its wake. In those cases, the obscurity of the music always seemed to matter more than whether I actually wanted to hear it. I’d say Lenny Kaye deserves a lot of credit; he selected cream. (The 1998 reissue/expansion dug up a lot more great music, but those extra songs were often fairly popular in their day. I don’t think Nuggets makes a great claim for the power of obscurity.) I also always wondered why Nuggets referred to the “first psychedelic era” … had the term “garage rock” not been coined yet?

Thanks, Steven. I am always delighted to have you as a reader, but particularly in this case. Perhaps I should have made it clear that the “conservative” aspect to the 40th-anniversary reissue of Nuggets is one agreeable to my own taste, since, yes, that original 1972 collection does stand head and shoulders above most compilations from that era.