What is the best way to handle a legacy of extremism? This is an important question for every democratic government, but particularly in those nations where radical ideology once held sway. And Germany remains on the top of list. No matter how stable the post-war Federal Republic’s political institutions, the Third Reich is never too far from people’s thoughts.

That’s why, even though Far Right movements in France, Italy and now Greece have posed a more immediate threat to the established order than in Germany, anti-fascist rhetoric plays such a prominent role in the latter’s activist circles. Calling one’s opponents “Nazis” packs a much bigger punch in that context, because the threat it conjures is a matter of historical record.

But invoking this term also poses problems. Like the proverbial boy who cried, “Wolf!” those who are always worrying about the return of fascism run the risk of diluting the concept to the point of uselessness. Coupled with the endless parade of Nazi villains circulated by the global Culture Industry, this reflex can, if left unchecked, actually make it impossible to distinguish real threats from imagined ones.

The recent debate in Germany about whether to ban the long-established National-Democrat Party (“NPD”) brings this issue into sharp relief. In nearly fifty years of existence, the party has never managed to exceed the 5% electoral threshold necessary to have a parliamentary presence. Whether in good times or bad, it simply hasn’t managed to convince a significant number of voters to embrace its repackaged ressentiment towards a world intent on keeping Germany down.

Were the party to be banned, however, its supporters could claim to have been a much bigger threat than they actually were, thereby securing the reputation that the movement needs to grow. Paradoxically, declaring the party illegitimate could give it an aura of legitimacy. At the same time, ignoring the party could also lead to trouble. If Germany’s fortunes suddenly took a sharp turn for the worse, as those of Greece, Spain and Italy have done, the existence of a functional organization could make it easier for neo-fascists to gain political leverage. This is what happened in the Weimar Republic, after all, though the absence of a 5% threshold made it much easier for radical parties to make an immediate impact.

When anti-fascist activists decide to confront their enemy in public, as they did last year during a series of “Pro-Germany” demonstrations organized by the Far Right, they need to be sure that they aren’t serving as inadvertent publicists. They would also be wise to think long and hard about their rhetorical strategy.

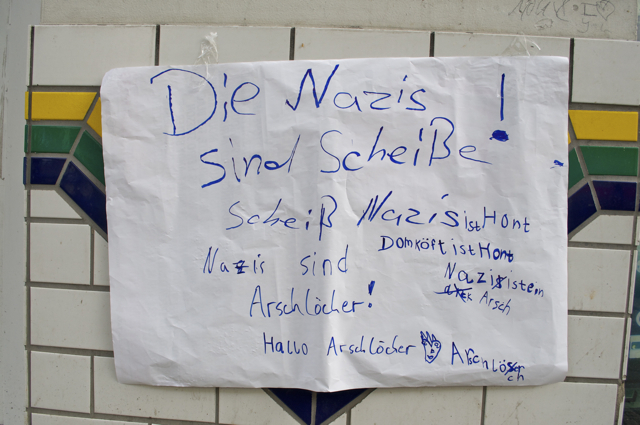

This handwritten sign, posted alongside flyers announcing plans for the counter-protest, testifies to the difficulty of getting participants to articulate a coherent, effective message. Whether its half-assed quality is deliberate or not, the insistence that “Nazis are shit” and “Nazis are assholes” — the sort of ritualistically deployed imprecations that everyone has long since learned to tune out — undermines the sincerity of this particular protest, suggesting that participants are simply going through the motions.

Mind you, there is something refreshing about the way that this sign cuts the earnestness of the official flyer, with its neat-and-tidy layout and tasteful use of color. There was definitely a time, during the early years of the counter-culture, when its crude language might have seemed almost revolutionary, an exuberant rejection of the establishment’s insistence on public decorum. But it’s different now. What might once have passed for irreverence now comes off as the product of sheer boredom. And that’s the last thing the anti-fascist movement wants to communicate.

Commentary by Charlie Bertsch. Photograph courtesy of Joel Schalit.