What does it mean to be an anti-fascist? Never easy to answer, today this question can seem like a Zen koan. First you have to decide what constitutes fascism. Then you have to figure out how to oppose it. Beyond those groups that deliberately invoke the iconography of brown and black shirts — a small number, relatively speaking — there is a wealth of potential enemies. The challenge is to choose them well.

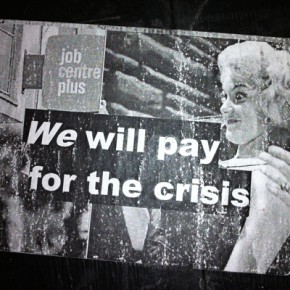

As the Euro Zone struggles through wave after wave of economic instability, the Far Right is achieving a level of political clout unprecedented since the end of Franco’s reign. At a time when governments are forced to acquiesce to the demands of a supranational technocracy, the dream of a state that can stand up for itself holds great appeal. This poses difficulties for leftists, particularly those with an aversion to all forms of centralized power.

In theory, they should welcome the withering away of national autonomy. But austerity capitalism promotes this tendency, not for the international solidarity of the working classes, but the financial advantage of a select few. Calls for state intervention to preserve workers’ contribution to the economy, the safety net that they have paid into so dearly, are problematic. Yet the alternative might be worse.

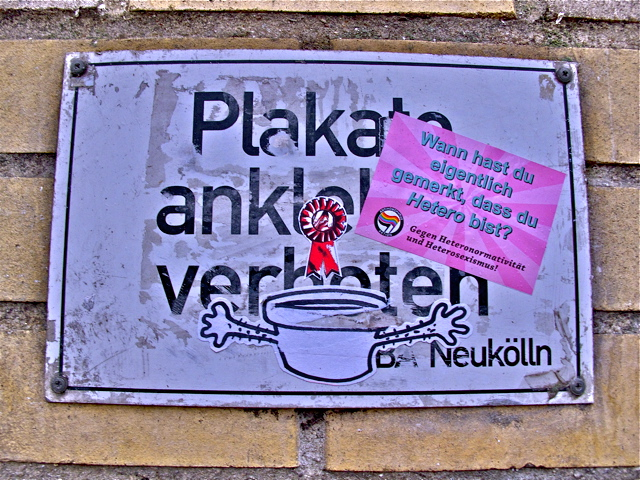

These two stickers, photographed in Berlin’s Neukölln neighborhood, represent a delicate balancing act. Neither one addresses the Far Right directly. Rather, they make the case for extending the definition of fascism to include all forms of intolerance.

The first, ironically superimposed on a sign forbidding the application of posters and stickers, tackles discrimination against the LGBT population. A provocative question, “When was it, exactly, that you noticed that you were hetero?”, is followed by the slogans, in smaller print, “Against heteronormativity and heterosexism.”

Given the Nazis’ brutal discrimination against those identified as homosexuals after the suppression of the SA, there’s clearly historical precedent for identifying this message with the anti-fascist cause. The same goes for the second sticker, which concentrates on the plight of the disabled, another group the Third Reich targeted for elimination. “Why don’t you sit in a wheelchair?”, it reads, followed by the slogans, in smaller print, “Against able-ism and the pressure of normality.”

In both instances, we are encouraged to conceive of anti-fascism as a “Big Tent” philosophy, that embraces not only the battle against the resurgence of 1930s-style Far Right radicalism, but also the softer forms that it appears to assume in contemporary democratic societies.

The problem with this approach is that, like the battle against austerity measures, it can easily seem like an endorsement of government-led initiatives. If you are as resolutely opposed to the state as most “ANTIFA” groups claim to be — tellingly, the second sticker is paired with a Czech “Stop Vládě” sticker that literally translates as “anti-government” — the goal must be to argue against discrimination without simultaneously advocating for politico-juridical actions to prevent it. Bearing this in mind, the questions posed in these two stickers personalize the issue, urging readers to identify with the plight of groups traditionally deemed “abnormal”.

Translated from the German by Charlie Bertsch. Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit.