While David Cameron’s recent wreath-laying ceremony in Amritsar was a welcome gesture, his failure to apologize sent an ugly message. Though the Prime Minister rightly acknowledged that the 1919 massacre by British forces was “deeply shameful,” such an act remains worthy of contrition.

Given that Cameron was willing to apologise for the 1972 Bloody Sunday massacre – an execrable crime, but one that led to fourteen deaths, not hundreds, as in Amritsar – this decision not to do the same abroad, in India, reflects a serious lack of consistency.

Are Punjabi lives worth less than those of Irish Catholics? Just how bad, one is tempted to ask, do Britain’s colonial crimes have to be in order to warrant an official apology? It’s not as though the Indian government is demanding reparations. Such questions prompt troubling thoughts when one reflects on just how horrendous the incident in question was.

A review of the events that day suffices to hammer this home: nearly 400 unarmed men, women and children were butchered by British troops, in a city park, in the holiest city of the Sikh religion. The protesters had gathered, very understandably, to show their opposition to the heavy taxation and forced conscription of Indians, who were being compelled to fight in service of an oppressive Imperial power that they did not wish to be governed by, let alone die for.

This occurred at a time in which Britain had resolved to crack down on internal unrest in the country. In order to achieve what commanding officer Brigadier General Reginald Dyer believed would be the “moral effect” of murdering innocent civilians, presumably to “educate” them not to commit the offence of daring to stand up to imperial imposition, an expedient outburst of extreme violence was deemed necessary. Prior to the assault, which only ended when the British forces had expended all of their ammunition, all exit routes from the scene of the massacre had been blocked so escape was impossible. Dyer’s punishment for this atrocity was to be removed from his post, and to face the relative disgrace of an official inquiry.

Adding to the extreme shamefulness of the whole episode, as the journalist Sandip Roy rightly reminds us, many Britons disapproved of even this mildly punitive measure against Dyer. He notes that many members of the British middle and upper classes lionized the military “hero”, and some went so far as to raise “26,000 pounds sterling for his benefit. A women’s committee presented him a sword of honour as the “Saviour of the Punjab.” Brigadier-General Michael O’Dwyer, the Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab, called Dyer’s use of force “justified.” All of which makes one think of Gandhi’s celebrated reflection on western civilization, or the lack thereof.

The Mahatma’s remark was again brought to mind by the Prime Minister’s visit to the Punjab. Having made this week’s belated official gesture over the Amritsar atrocity nearly a century too late, and while still on Indian soil, the PM however did not forget to mention “the good” that Britain’s departed empire had done. He did not elaborate beyond this vague (in the circumstances hopelessly tasteless) statement, and identify exactly who the chief beneficiaries of this supposedly sometimes-benign empire really were. As everyone knows, for the most part they were not Indians, but rather the British merchant classes, who grew unimaginably wealthy, while ensuring that their needs were “most grievously attended to” by Westminster, as Adam Smith critically observed as early as the 18th century.

In order to understand why certain writers like myself may find sentimental views of Britain’s bygone era of dominance both deluded and infantile, it is worth remembering the sort of impact that Britain had on the people of the subcontinent by recalling some of the more sobering examples of the UK’s “civilizing” influence in the area.

A legacy of drug addicts and mass starvation on either end of the Asian supply chain ensued when the East India Company (the world’s first official corporation) forced Bengalese farmers to abandon food crops for opium to sell to China. Subsequently, the population of Dhaka, modern Bangladesh’s capital city, at that time a dominant regional centre, declined by 150,000 to 30,000 within a century of British rule. No amount of casuistry from the viewpoint of cold historical distance in lofty panegyrics by Niall Ferguson about our gifting of railways, parliamentary democracy and the print media to the subcontinent will convince me that British-inspired “progress” in India (the usually-cited “good” we did there) came at a worthwhile human cost. Quite the reverse: the history of Britain’s colonial presence in South Asia is littered with clusters of outrages and injustices that we shouldn’t hesitate to acknowledge and apologize for given the sheer immensity of human misery caused.

Yet even the murders in Amritsar, and the immiseration of the Bengal, are mere footnotes to the full, multi-volume criminal saga of Britain’s imperial adventures throughout the world. While some small positives (travel infrastructure) may have come out of the biggest empire in history for its non-British subjects, when set against multiple genocides, the slave trade, famines, pillaging and massacre to feebly say “don’t forget the good stuff” seems obscene, even sinister.

Of course there’s no need for modern Britons, including the Prime Minister, to feel directly responsible for the massacre in Amritsar (or the empire generally.) However, it was churlish of Cameron not to proffer a response more proportionate to the seriousness of the crime. By failing to give something that costs us nothing (an apology,) over something that caused such pain, the British government showed that it has a long way to go to achieve the magnanimity of their more civilized counterparts on the post-colonial world stage.

One example of the latter, from recent history, was represented by the Mandela government. in post-apartheid South Africa, overwhelmingly representing the victims of imperialism, who sought internal reconciliation after coming to power. Cameron and his coterie, by comparison, the modern inheritors of the party of class war and foreign plunder, have few reasons to feel at ease with the past.

As an after-thought on the whole affair, I’d like to quote the considered if pointed reflections of Cambridge University’s Priyamvada Gopal: “Saying sorry, not saying sorry, half-saying sorry. It’s all absolute bunkum. Just acknowledge that the empire was a dismal project overall and lots of people died in lots of massacres and famines, teach schoolchildren the real history, and we can be done with these sorts of performances and have a more productive discussion.”

While I feel strongly about the lack of an apology, Gopal’s points remain valid. However, given that the Tories, and a considerable portion of the left intelligensia have mounted inadvertent or conscious defences of empires old and new, the chances of such a modest corrective, in the UK at least, remains doubtful. Yet another reason, why a Conservative Prime Minister might dispense with a little humility. After all, if Dave can do it, any Briton can.

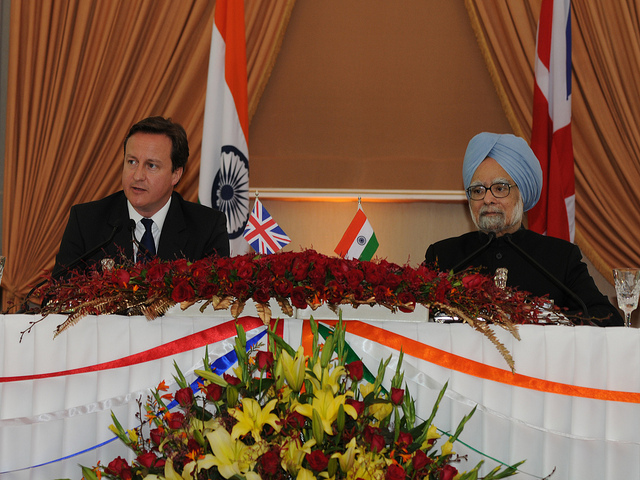

Cameron/Singh photograph courtesy of The Prime Minister’s Office. Amritsar screenshot courtesy of Gwydion Williams. Published under a Creative Commons license