The Academy Awards had its share of surprises, but none more significant than the end of broadcast cutaway to the White House, where the First Lady helped presenter Jack Nicholson announce the winner of the Oscar for Best Picture. Like many of the media events sculpted for the Obama Presidency, this high-tech exchange stopped many viewers short.

To be sure, this break with Hollywood precedent was handled with aplomb, like most of Barack and Michelle’s public appearances. Yet the slickness of the moment, the sense that politics and entertainment had been perfectly synchronized — particularly on a night when the aura of professionalism had otherwise been lacking — left a lot of people uneasy, even if they couldn’t pin down a reason for their feelings.

I was among them. It wasn’t until I watched Best Actress winner Jennifer Lawrence’s refreshingly awkward press conference after the ceremony that the gears in my mind started to engage properly. Because although her performance in Silver Linings Playbook was impressive — I still think she was a bit young for the part — I identify her more with the role of Katniss Everdeen she played in The Hunger Games. And the questions she was getting about her preparations for the evening and the trouble she had climbing the stairs to accept her award viscerally recalled the struggles Katniss has coming to terms with her sudden fame. Instead of passively consuming another pro forma ritual of the entertainment business, I started to notice parallels between the Academy Awards and the spectacle in which the teenagers from the Hunger Games find themselves.

I also realized that, despite enjoying massive success at the box office and generally good reviews, The Hunger Games had been completely ignored by the Academy. Mind you, there’s nothing new about the Academy Awards slighting what were once classified as “pulp” genres such as science fiction and horror. In the case of The Hunger Games, Lionsgate didn’t even bother to screen the picture for voters, no doubt presuming that the exercise would accomplish little. But it’s also true that The Hunger Games’ dystopian tale of America’s totalitarian near future strikes too close to home for Hollywood’s comfort.

While The Hunger Games, like the Suzanne Collins young-adult novel on which it’s based — I discuss the trilogy at greater length in this piece — has sufficient teen romance to be marketable, the film differs sharply from the Twilight series to which it has too often been compared. Instead of an age-old story of vampires and werewolves in which modern political institutions and the ideologies that sustain them are ignored, The Hunger Games confronts us with a world gone wrong that is clearly extrapolated from the reality we inhabit now, showing us what may happen when the desire to consume other people’s lives becomes so intense that reality — or at least a highly processed take on it — becomes more compelling than fiction.

This prospect resonates for anyone who has experienced the ascendance of shows like Survivor and The Bachelor, Big Brother and The Real Housewives of New Jersey, as well as more traditional forms of documentary. But the depth of its impact depends less on these commercial offerings than the social media that have helped to raise their stature. Anyone who has felt the pressure to use services like Facebook and Twitter will grasp intuitively how fleeting privacy has become. Even those who refuse to participate in this activity have heard horror stories about the overexposure it makes possible. Simply put, we live in a new form of surveillance society in which the doings of ordinary people are not only recorded to an unprecedented extent, but also serve as a prime source of entertainment for others.

Some have argued that this trend represents a new mode of democratization, in which fame is no longer monopolized by the culture industry. But The Hunger Games reaches a far more pessimistic conclusion suggesting that the stardom available to us in the era of reality programming is actually an index of our powerlessness in the face of invasive technological scrutiny. Celebrity, as Katniss and her fellow participants in the Hunger Games discover, is an instrument of political power. If the influence of the culture industry as we know it has waned, it is simply because its functions have been seamlessly absorbed into the state.

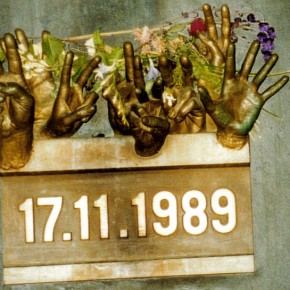

The Hunger Games deftly turns twentieth-century-style totalitarianism, which had once seemed destined for the proverbial dustbin of history, into the logical outcome of our supposedly post-totalitarian era. In particular, it directs our attention to the immediate aftermath of the Cold War, when the sudden collapse of the Eastern Bloc briefly left the United States as the globe’s sole superpower. It was in this period of transition that both the internet and reality programming first came to prominence, a development that seems, in retrospect, to imply the existence of a Law of Conservation of Surveillance, with the low-tech approach of state agencies like the STASI of East Germany giving way to more insidious forms of control.

Not coincidentally, this was also the era in which Hollywood refashioned itself as a purveyor of superior technology, making the special-effects blockbuster into its global calling card. Even as the Academy Awards continued to honor traditional filmmaking, with its emphasis on actors, writers and directors, the balance of power within the industry had shifted to the technicians who could literally conjure worlds from scratch. Paradoxically, right as reality television and faux documentaries like The Blair Witch Project were taking the public by storm, cinema was becoming less constrained by external conditions than ever before.

From this perspective, the Oscars could be plausibly described as an elaborate ruse, in which the technological and financial reality of contemporary Hollywood is concealed by an appeal to tradition. Last year’s winner of the award for Best Picture, the neo-silent film The Artist — see my piece from last year for more in-depth discussion — was a perfect example. But so, in its way, could this year’s little-film-that-could nominee Beasts of the Southern Wild, its low-budget DIY approach metonymically standing for the virtues the industry holds dear. Or Amour, Michael Haneke’s brutally claustrophobic tale of old age, in which the very idea of special effects seems preposterous.

What interested me most about this year’s ceremony, however, were the moments when this bait-and-switch threatened to break down. The sequence in which Mark Wahlberg presented together with his “co-star” from the raunchy comedy Ted, a computer-generated stuffed bear voiced by host Seth MacFarlane, stands out, as did the skit in which the original Star Trek’s William Shatner supposedly traveled back in time to warn MacFarlane how he was going to screw up the show. For me, though, the sight of the First Lady, surrounded by fresh-faced young people in military regalia, was most telling.

When you think about it, the White House’s involvement makes a lot of sense. After all, three of this year’s Best Picture nominees, Zero Dark Thirty, Lincoln and the winning picture Argo — see my piece on the latter from October — concern the exercise of Presidential power. Together, they give a new twist to the vision of American exceptionalism that Hollywood has long promoted. Because although they still cheerlead for the nation’s commitment to freedom, they also justify its pursuit by any means necessary, implicitly sanctioning the expansion of executive privilege that accompanied the Patriot Act after 9/11. In short, they promote Presidential liberty.

More subtly, the First Lady’s surprise appearance testifies to the mutual recognition, by both Hollywood and the White House, that political and cultural imperialism are inextricably bound together. We are accustomed to thinking of the technological innovations of so-called “peacetime” industries separately from those of the military-industrial complex. The truth, however, is that Hollywood has always played an important role, not only in supporting the Pentagon through overt and covert propaganda, but by perfecting many of the devices and techniques that have given it an advantage over the nation’s enemies. And that is the case today more than ever.

But the synergy doesn’t stop there. In movie after movie, Hollywood communicates the message that being under constant surveillance is the price of freedom. Think of all the plots that center on attempts to evade scrutiny, yet ultimately convey the futility of doing so. Even when the good guys — or the bad ones — get away, we see them being seen, usually by security forces of the state. Although we may identify with those characters, we are also encouraged to identify with the position from which their actions are recorded on video. The result is a profound psychological schism, in which we learn to see ourselves as the impersonal eye of the camera sees us, learning to occupy the role of potential informer.

To be sure, this is not a new phenomenon. In one sense, cinema has promoted this sort of panoptic consciousness from the get-go. The difference is a matter of degree. Never before have so many people had access to the means of capturing themselves and others in motion pictures and then distributing those recordings to a potentially global audience, effectively becoming members of the media.. Both Hollywood and the White House recognize this state of affairs as a threat to their power. Yet they also understand that, if they handle things right, this surfeit of surveillance can still serve them well, particularly if they work in tandem. What better proof could there be than this year’s Academy Awards?

Screenshot courtesy of The Ocars 2013. All rights reserved. Obama mural courtesy of ChiaLynn. Published under a Creative Commons license.