Former squatter Hannah Dobbz’ Nine-Tenths of the Law: Property and Resistance in the United States (AK Press) couldn’t arrive at a more fitting time. The housing crisis unquestionably complicated and challenged Americans’ notion of the American Dream of universal homeownership, leaving fertile ground to explore and question who or what grants the right to live in a dwelling.

Before the housing crisis, it would have been unthinkable for a U.S. politician to mention squatting, let alone advocate it, as Ohio Democrat Marcy Kaptur, did in 2009. “So I say to the American people, you be squatters in your own homes. Don’t you leave,” she said as her district faced both epidemic foreclosures and unemployment. Kaptur noted at the time that possession is “nine-tenths of the law. Therefore, stay in your property. Get legal representation.” Indeed, Americans who would have never before imagined themselves squatting – and may have had no idea what the term means – suddenly found themselves on a thin line between the American ideal of homeownership and the often demonized concept of squatting, the latter of which Dobbz acknowledges “has never had a particularly good reputation in the United States.”

As Dobbz’s book shows, the desperate measures that these residents of foreclosed homes were forced to take were by no means without historical precedent. One of the many strong points of Nine-Tenths of the Law is its use of anecdotes from the distant and recent past to trace the history of property ownership and resistance in the United States, which Dobbz points out, was founded by squatters. For instance, she describes how the nineteenth-century residents of Rensselaerwyck (now the Albany and Rensselaer counties of New York) struggled for 26 years in their Anti-Rent movement against the archaic form of Dutch feudalism in which they were trapped.

Albeit with some successes along the way, the Anti-Rent movement ended with disappointment, the effects of which can still be felt today. “The Anti-Rent incident dispelled the American notion of democracy for many nineteenth-century contemporaries who questioned how, in a country of ‘free’ people, the violence of the state could be utilized as an arm of private tycoons to silence the majority,” Dobbz writes. Though the Dutch patroonship system that these early New Yorkers faced is distant history, this same questioning that their incident prompted is still highly relevant today.

Possession is indeed nine-tenths of the law, yet the conflicts experienced in Rensselaerwyck during the nineteenth century and in the foreclosure crisis of the twenty-first century show that possession of real estate is not as clear-cut as one might think. Who possesses a property when the person or people living in it are different from who or what has the legal title? Take, for example, a foreclosed home that is occupied by squatters. Who should have the right to the property – the bank that holds the defaulted mortgage, the family that lived in the home before defaulting on the mortgage, or the squatters physically residing in the property?

The answer to that question depends on one’s own views. Even when Bay Area squatter Steve DeCaprio tried to claim adverse possession of a property formerly owned by a deceased man with no legal heirs, the fate of DeCaprio’s claim depended on the presiding judge, whom DeCaprio decided “was completely opposed” to giving him the title. As Dobbz explains, claims of adverse possession are rare but are sometimes won, such as when in 2009 an anonymous couple won 55 percent of their neighbors’ land they had been using in an “open, notorious, visible, and hostile” manner for the statutory period of 21 years.

For those seeking alternative means of residency to property ownership and renting, Nine-Tenths of the Law offers a spectrum of possibilities. For those looking to squat, Hannah Dobz provides advice culled together from expert resources, such as DeCaprio’s step-by-step process for researching abandoned properties and squatting tips from members of Organizing for Occupation in New York City. However, squatting is not in line with everyone’s personal tastes and so Dobbz also offers other alternatives. For instance, she describes 28-year-old Shirley Mason who took the “backdoor to homeownership” in Pittsburgh, buying the debt of an abandoned home from the bank, taking the property to sheriff’s sale and paying back utility fees and taxes on the property. All in all, Mason estimates she got the property for a total of $12,500 in expenses. Of course, that’s a fraction of what a home bought in the traditional manner would cost. Dobbz also provides an entire chapter on housing cooperatives, including a financial projection table for co-op housing.

To be sure, Nine-Tenths of the Law can serve as a guide for anyone considering squatting, co-op housing or Mason’s “backdoor” route to homeownership. However, it’s more than a how-to book, as it raises important issues that are especially pertinent in the aftermath of the housing crisis. As Dobbz writes, “The historically contradictory reaction of Americans to the foreclosure crisis is reassuring … And with squatting once again in the mainstream discourse, the potential to overhaul the way we do housing and the way we view resources creeps closer to a new reality.”

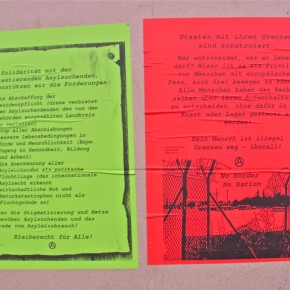

Photographs courtesy of Viqi French and Punk Nomad. Published under a Creative Commons license.