Thirty years into the Islamic Republic, Tehran was transformed by an explosion of youth, and a demand for higher education. Globalization hadn’t only affected the economic and political strategies of the government. It had affected the structure of Iranian society. New communication technologies arrived, and the country was opened to global culture, defining a new generation. These new technologies created a revolution that decentralized, disembodied, and delocalized Iranian social relations. Iran had entered the age of neoliberalism.

Iranian political theorist Farhang Rouhani argues that the Islamic yuppie is the product of this era: a new generation of well-educated, young urban professionals who grew up simultaneously under the influence of the Islamic Republic and global neoliberalism. Rouhani’s Islamic yuppies profess to being Muslim, as well as Iranian nationalists. For these new Iranians, faith increasingly became a matter of private practice, rather than a matter of public debate. Religion is only significant in the public realm, to the extent that it informs and educates private individuals. Otherwise, it remains personal.

The Student Reform Movements and 2nd of Khordad Front are also products of this period, and were equally a result of Iranian society’s exposure to neoliberal globalization. Since 1999, these movements, and their protests, laid the foundation for future demonstrations in the country. This helped pave the way for the Iranian public to break its historic silence and criticize the government, to find new means of expression, and exercise its rights.

In June 2009, one of the most important political events in the country’s history occurred, with the advent of mass protests against the results of the presidential elections, and the government’s restrictions on social and private life. These demonstrations brought millions out on to the street, catching both the government, and the international community, by surprise. According to The New York Times, the June 15th protest “involved hundreds of thousands of people and was one of the largest protests since the Islamic Revolution 30 years ago.”

Tehran, in particularly, played host to huge numbers of Iranians taking to the streets, demanding their rights. The city’s streets became a new medium of communication between the the people and the government. They became a place for Iranians to express themselves and to be heard, where they could create their own collective memories, and participate in the country’s democracy. However, these public spaces weren’t communicative ends unto themselves. They were part of something larger.

Unlike the 1979 Revolution, when government-controlled media published news of the event in accordance with its own agenda, communications technologies such as the Internet and mobile phones turned every Iranian into their own media. The slogan “each citizen, a media” clearly expresses the role of new technology in the organization and creation of this Iranian movement. Media and social networks such as Facebook and Twitter served as their communications and publishing outlets, prefiguring their use in the Arab uprisings of 2011.

Instead of using the walls of the city to publish their rights and slogans, Iranians used the walls of social networks for publishing news globally and locally, as well as for organizing their protests. All the main streets and squares involved in the protest were connected together and unified. An all-encompassing view of Tehran was thus made available to participants. By way of the Internet and their mobile phones, demonstrators had an overall understanding of the protest in different parts of the city, and how it was changing. Protestors were notified to reorganize based on information distributed and updated online.

Demonstrators also used their mobiles to capture events, take pictures and videos, share their individual experiences with others, and publish their news globally. Though this appears commonplace to revolutions now, one cannot underestimate what this signified to participants at the time: recorded events appeared more pluralistic and visual than ever before, as though they were composites of numerous peoples’ testimonies. This, in turn, inspired a new kind of solidarity, not just amongst Iranians, but for the outside world, with domestic Iranian struggles.

A crucial point for the Green Movement was that the 1979 Revolution was still alive in the memory of Tehran and its inhabitants. All the public spaces involved in this uprising still bore its memory. Unsurprisingly, places of gathering in both uprisings tended to be the same. For example, the largest demonstration was planned to take place from Enghelab (Revolution) Square to Azadi (Freedom) Square.“As Enghelab ta Azadi” (from Revolution to Freedom) was a slogan among protestors, a symbolic reference to these two places. Since Freedom Square is the center of commemorations of the 1979 Revolution, protestors planned to gather in Azadi, show their numbers, and demonstrate against state-organized celebrations.

Indeed, such location-conscious protests spoke to another ingenious aspect of Green demonstrations: how they reconciled different moments in Iranian history. For demonstrators seeking to provide themselves with mainstream political legitimacy, this was a well-thought out move. Given the degree to which the Green Movement considered issues of space, online, and took advantage of the freedom that it offered, it ended up finding the same offline, in the streets of Tehran.

The irony is of course obvious. New communications technologies made it possible to create one of the greatest protest movements in Iranian history, while remaining, when all was said and done, under the control and limitation of the government. As Marshall Berman once wrote: “All my conscious life I have wanted to be a citizen-that is, a person who proudly and calmly speaks his mind. For ten minutes I was a citizen during the demonstration.” One could say the same for Iran’s Green Movement, too.

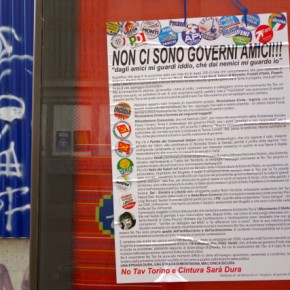

Photograph courtesy of Nima Fatemi. Published under a Creative Commons license.