Few continents have been as lost on the left as Africa. That doesn’t mean there haven’t been openings, however. From the anti-Apartheid movement of the 1980s, to the Arab Spring, there have been plenty of opinions on offer. But, the idea of Africa, as a site of political struggle, between the West, and its inhabitants, is relatively new. That is, to post-Cold War progressive politics. Ask veterans of the anti-colonial struggle in France, for example, from the 1960s, and you’ll get a very different answer.

Hence, the challenge of France’s recent intervention in Mali, and the complexities it engenders. Led by a leftwing French government, one that made the furthest attempts of any French leadership to date, to atone for France’s conduct in the Algerian conflict, its actions have been confounding. Coming on the heels of other recent European military operations in Africa, most signfiicantly, the Libyan War, many progressives as begun a process of soul searching, about their lack of preparedness for these interventions, and what they might mean.

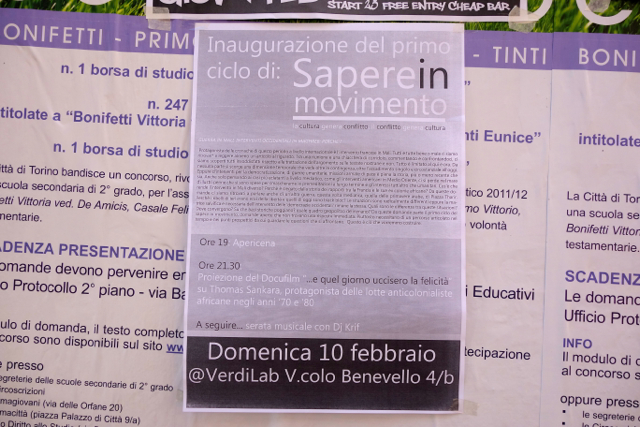

Today’s translation from the Italian is a good example. A flyer found in central Turin, at the beginning of February, it asks precisely these sorts of questions. We’ve reproduced the text in its entirety, below, including the lack of line breaks. Click on the photograph for a closer look.

Opening of the first series of: “Knowledge in motion”

Culture creates conflict, conflict creates culture

Mali war, western interventions in Maghreb: why?

One of the main subjects of international press (right now) is France’s intervention in Mali. Everyone, more or less, has read at least one article about this topic. Between a meeting and small talk, we found ourselves unsatisfied with regards to how the subject is treated in Italian and foreign newspapers. Everything is limited to the “here and now.” It’s not possible to find a temporal dimension that goes beyond contingency, beyond the single, today-related event. Nonetheless, history, more or less recent, is full of interventions for democratization, of humanitarian wars, of armed missions for peace. Only thinking of the most striking cases in the international media, such as US intervention in the Middle East, you could get lost among the unaccountable journalists who attempted to reveal the long-term premeditation and interests, all but humanitarian. What makes Mali intervention different? Why is it disconnected from the history of relationship between France and its African former colonies? Starting from these questions, we found ourselves talking about another war, a media one: the Arab Springs, Tahrir Square. Why yesterday’s rebels were freedom heroes, while today’s are black bloc? Situations are radically different, but, (for) the redeeming and necessary essence of the “western democracies” intervention remains the same. Which are the differences between these situations? Where do they converge? On which historical basis are they founded? Which geopolitical scene do they outline? From these questions begins the first series of “knowledge in motion,” open questions that have no immediate answer. Rather, they require a well-structured, timely analysis, (offering) different points of view. This is what we would like to create.

7 pm dinner

9.30 pm shooting of the docu-movie “…that day they killed happiness” about Thomas Sankara, key figure of the anti-colonialist Africa struggles in the 70s and 80s

Following: music with Dj Krif.

Sunday 10th February @ VerdiLab Vicolo Benevello 4/b

Translated from the Italian, by Giulia Pace. Introduction and photograph courtesy of Joel Schalit.

Speaking as a historian of Africa, and a sometime activist with the Association of Concerned Africa Scholars, I would suggest that for a start, you ought to critique both the Italian flyer and your own response to it in terms of the desire to treat the relevant unit of analysis as “Africa.” Why is a film on a revolutionary president of Burkina Faso held by Italian left intellectuals to be likely to help their understanding of interventions in Mali? Might this be as misleading as trying to gain insight into U.S. politics by watching a film biography of the former premier of Saskatchewan and founder of the New Democratic Party Tommy Douglas? If you already know enough about the history of the two countries to be able to interrogate the commonality of the term Medicare, you might learn something, and Thomas Sankara may have some connection to political or social forces in Mali, but it is not the place for people who confess ignorance to start.

There are complex reasons why this occurs. There is the legacy of deracination of enslaved Africans from their particular cultural heritages in the U.S. and elsewhere, the use of a common racist rubric of Africans as unified by their blackness, held in various mystified ways to justify their domination and oppression. There is the counter effort, roughly on the left, to construct an often racialized Pan-Africanism as a form of resistance forced upon Africans and the African diaspora by the terms of racialized domination. The fact remains that Africa is not a country, and if you really want to be serious about a left politics about particular interventions, you have to get below the level of the continent.

You might also investigate the actual left intellectuals who *do* engage with Africa. ACAS would be a good place to start. African Action (formed by a post-anti-apartheid, post Cold War merger of the former American Committee on Africa and Africa Policy Information Center) would be another place to turn. An important resource is AfricaFocus, run by activist intellectual and author William Minter. Black Agenda Report often carries strong Africa materials.

On the other hand there are probably things to be interrogated about why left-leaning Africa scholars let themselves be so encapsulated. Why have they/we been so ineffective after 60 years of organized Africa scholarship, mostly aligned in left or liberal ways (though Newt Gingrich’s Ph.D. was on the Belgian Congo) with African liberation movements and their successors, in changing the basic U.S. cultural discourses on Africa, and perceptions of it? Is their/our non-inclusion in any cohesive way on organized left, such as it is, a defect of scholarly ivory towerism, of uninterest among other leftists, or both? In the 1970s or 1980s left engagements around South Africa, Southern Rhodesia/Zimbabwe, Angola and Mozambique, Mobutu and the CIA in Zaire, attention to revolutionary figures and their downfall in West Africa did figure on the left. What happened in the 1990s, despite bits of attention to oil politics in southeastern Nigeria, and genocide in Rwanda? Is it just the shrunken and atrophied character of the left in general that has left Africa in an attentional vacuum until renewed imperialism on the continent forces response? Is it subconscious racist deprioritization by white leftists? Is it the victory of media hegemony portraying Africans as helpless, hopeless basket cases at best, or of marginal humanity at worst?