It would be wonderful if real life were like a Hollywood movie, where we have the good who are pure ,and the bad who are irredeemable. In Syria, life is all too real and the combatants are complex figures. You’d hardly know that, though, from the rhetoric coming from the United States.

Perhaps most disappointing has been a segment of the left, which has been overtly supportive of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. This seems to be a knee-jerk reaction to the US support for the uprising.

This segment of the left, which likes to believe itself to be the most accepting of the “other” in every instance actually comes off as condescending, believing that the uprising is a Western construct. This echoes Assad’s own propaganda, which characterizes the Syrian opposition as “foreign-backed and full of foreigners fighting the Syrian regime.”

On Facebook, I saw several US activists lift the following quote from a Turkish anti-government/pro-Iran, and Hezbollah news source: “Bashar al-Assad has recently been demonized by the mainstream and so-called alternative media who claim that he is a brutal dictator. Actually Bashar is a reformer who has done much to further the causes of democracy and freedom.”

The interventionist rhetoric is no better, but much more widespread and mainstream. The US State Department’s spokeswoman, Victoria Nuland, characterized Assad as “evil” and “unfit to rule,” to cite one of legions of examples. Whatever people may think of that characterization, its use as political rhetoric is meant to stir emotion and defeat rationality.

The numbers in the Syrian civil war are staggering, and continue to build. Some 70,000 dead, and over a million are refugees. These are horrifying statistics. Anyone who looks at them cannot help but feel an urge to see their government, indeed the entire world, rush into Syria, stop the carnage and remove Assad from power. But it is vital that we recall the history of foreign interventions. They have a pretty poor track record. At the same time, standing by and doing nothing just feels unbearable.

Neither wild conspiracy theories that rob the Syrian people of their own agency and blame the civil war on foreign imperialism, nor a blind rush toward regime change gives us the answers we need. Meanwhile, France is ready to charge in unilaterally, because, of course, they did such a bang-up job creating and shepherding Syria and Lebanon into the 20th century. And every day, voices in the US grow louder, urging intervention and harshly criticizing Barack Obama for not “doing something.” In the United States, the basic axiom that if all you can do is harmful then doing nothing is preferable is still lost on many, especially in Washington.

Still, intervention needs to be seriously considered, even if that intervention would be self-serving and imperialistic in nature, simply because the situation in Syria is so bad. But whether or not to support intervention is a question that can only be realistically assessed with a clearer look at Syria, and what is happening there. We need to ask all the questions: do we think the fall of Assad will lead to a better government in Syria? Would Western intervention really help the opposition or taint it? Do we have any idea what would come next in Syria if we do help topple Assad, and if so, is it desirable?

These questions will have a variety of answers, depending on the worldview of the questioner. But wherever one ends up, a sober look at both the Assad regime and the opposition is required to sort it out. And in too many sectors that has been sorely lacking.

Bashar and the Assad Regime

Beginning with Assad, his demonization and his horrific crimes are both rather ironic. Seen as a much gentler man than his father, Hafez al-Assad, Bashar was originally hoped to be someone who was inclined toward a more democratic and open Syria than his father. Indeed, where Hafez always craved power, Bashar never seemed all that passionate about it, but simply accepted it as the inevitable consequence of his birthright.

But whatever ideals Assad may have once been identified with, he inherited a highly repressive government. In Syria, that repression was largely based on politics. Where it had to do with any sort of sectarian religious issues, these were usually issue-dependent, not theological. Assad’s regime was secular and, especially, but not solely, because the Assad family and many of its cronies were Alawi, sectarianism was actually something Bashar al-Assad wanted to tamp down, although his father used sectarianism expertly to maintain control and bolster the Alawi community. It was, after all, sectarian opposition to his father that had been the biggest threat to the regime in its early days.

One noted historian of Syria who got to know Assad to some degree, David Lesch, says that things changed for Assad “…after the assassination of former Lebanese prime minister Rafik al-Hariri in February 2005. He adopted a bunker mentality against the rest of the world because he really believed they were out to get him. And most of the rest of the world was out to get him. So I think I saw it from that point on.”

Assad made some minor reforms and offered vague promises of more changes after the Syrian uprising had been going on for a while, but few had much faith in these gestures. Indeed, when the first protests started and were generally non-violent, the government responded with overwhelming violence. This was surely a calculated move; Assad knew he had less to fear from an armed opposition than a large, unarmed one. But it also reflected the same sort of ruthless disregard for Syrian civilians that his father had displayed in the Hama Massacre of 1982, which ended five years of fighting between the Syrian government and religious Sunni groups, especially the Muslim Brotherhood. Estimates of the death toll in the Hama massacre range from 10,000 to 40,000.

There’s little doubt that Syria was a highly authoritarian regime all along. The many reports from human rights organizations over the years demonstrate a clear pattern of massive repression. However much Bashar Assad may have wanted to enact reforms in Syria, his actual record shows precious little departure from the actions of his father.

Still, when looking over Human Rights Watch reports from the past two years, it is striking how little is said about the armed opposition groups. One wonders, is that justified? Let’s look at the Syrian opposition.

The Opposition

There are any number of factions, with all kinds of ideologies at play in the Syrian opposition forces. Assad is, from all accounts, vastly overstating the number of foreign fighters involved in the opposition, though obviously details on demographics are necessarily sketchy. But similarly, Western media which portrays the opposition as having support from the overwhelming majority of the Syrian people is equally disingenuous.

The perception that there is some choice among opposition groups to back “Islamists” or “non-Islamists” is equally false. Virtually all of the opposition casts itself in religious overtones. In the early days of the uprising, before the armed groups dominated, there were strong and visible liberal-secular factions, although the Western media, not surprisingly, played up and exaggerated their size and influence. These days, such groups have largely been pushed to the sidelines as they are not engaging in fighting. The same goes for “radicals” vs. “moderates.” There is no guarantee at all that any part of the Syrian opposition will remain friendly to the US if and when they assume control over Syria. In fact, the likelihood is that there is no good horse for Washington to back.

Right now, the Free Syrian Army is the American choice. Salim Idriss is its leader, a Syrian general, educated in Germany, who defected to the opposition. His sway among the various factions is questionable, but not absent, and he is probably the least sectarian of the various Syrian leaders. But even if Idriss, or someone like him emerges as Syria’s leader, the politics of post-Assad Syria are unlikely to be the kind that works well for the US.

The groups that are fighting are divided among themselves. The divisions are, not surprisingly, often sectarian, though there are also some ideological divides and some territorial ones. Perhaps most crucially, and certainly ominously, opposition groups are also divided between foreign patrons.

While Western media often discuss the roles of Russia, Iran and Hezbollah in backing the Assad regime, much less attention has been paid to the brinksmanship among those backing the opposition. Turkey and Qatar, who would prefer to see a Muslim Brotherhood government emerge in Syria, are opposed by Saudi Arabia, Jordan and the United Arab Emirates. Each grouping is arming and funding different factions. The United States and other Western countries are trying to play the middle and bring the main actors – the Saudis and Qataris — together, but it is a narrow tightrope to walk.

But as reports of war crimes and serious human rights violations mount against many of the opposition groups, it becomes less and less clear how much popular support the uprising continues to enjoy. There have always been significant sectors of support for Assad, but certainly not a majority. Clearly the rebels as a whole and in terms of individual factions have support as well. But how strong is the feeling of ordinary Syrians trapped in the middle who simply want it all to end? It’s difficult to quantify, but it is surely growing.

Where Does the US Go?

The CIA has been working to support the Syrian opposition for some time, in one of the worst-kept secrets this side of Israel’s nuclear arsenal. Last year, the Obama Administration finally came forth and began more openly supporting the rebels, with aid currently escalating. But what has that aid brought? There is no decisive advantage that is apparent for either side, nor is either the government or the opposition winning hearts and minds in Syria. Quite the opposite, the feeling there seems to be a stark division between supporters of both and a growing feeling among many that wishes a pox on both houses.

With the government and the various opposition factions receiving aid from their various patrons, no one is winning and the killing, dispossession and devastation continues. But the rebellion was no more started by the West than the Assad regime was birthed by Russia and Iran. Such conspiracy theories have not gained a lot of traction outside of the most fringe elements of the left, but it is good to be wary of them. Enough parts of the left thought opposing US aggression meant supporting the likes of Slobodan Milosevic or Saddam Hussein that there was damage done to the anti-war movement’s credibility. We have enough problems without that.

But even more mindless are the bi-partisan calls for direct US intervention, such as bombings or armed drones. The result of such action is completely unpredictable as to its success in ousting Assad and would only hasten what might be equally horrific violence as the various factions contend with each other to fill the power vacuum. But when influential voices, such as Democrat Jane Harman, leading Independent hawk Joseph Lieberman and Republicans John McCain and Lindsey Graham are all making similar calls for attacks on Syria, it’s inconceivable that the White House can just remain deaf to them.

In the end, one criticism of Obama’s Syria policy rings very true: the limited help he has given the rebels has probably done more harm than good. Of course, escalating that aid might well cause Russia and Iran to escalate their help as well. But even if they decide the stakes had become too high, the results of such US action could very well backfire. Foreign intervention in a civil war like Syria’s seems to be inevitable, but unlikely to produce good results.

The US should, of course, greatly increase its humanitarian aid, but this should go to all the people of Syria. The best course would be for the international community to find a way to bring the regional players – Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Iran – together to work on settling the Syrian conflict. But that is just wishful thinking. In the end, there really are no good choices in Syria. However, history tells us one thing: little good ever comes from Western meddling in the Arab world. Except maybe in the movies.

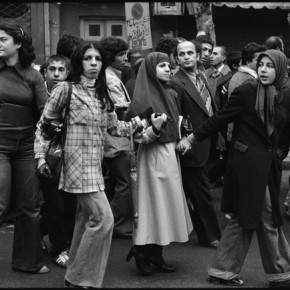

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit

I think this is the very best view I have seen and probably the best that can be given the ambiguity of the condition there. I have avoided tracking the conflict, even though I am the director of The Israel Palestine Project, and what happens in Syria is obviously very important to Israel and probably Palestine as well. That avoidance waS conditioned by the confused situation there and your article has supported my view as well as making the situation much more clear to me. Thank you so very much

jack Berriault

hello Mitchell, there’s much to be commended in your report. however, i am a tad baffled by your opening. with all this death, destruction and misinformation floating around, why say “Perhaps most disappointing has been a segment of the left which has been overtly supportive or assad” without even linking to or naming this “segment”? other than an allegation about several facebook activists, there’s no supporting evidence offered. i’ve never run into any US blog representing this ‘segment’. and the link you offer is to a turkish site i have never seen.

my observations are there simply is no ‘segment’ of the american left “overtly” supporting the regime. albeit, like you, there are many people who realize there’s not much upside here in supporting the opposition given the composition is sectarian in nature as your supporting links attest. would it be possible for you to link to an american blog representing this segment. thanks.

Annie, check out Brian Becker’s (of ANSWER) description of the situation here. Much as i wish they were not, ANSWER is certainly a segment of the left. http://www.answercoalition.org/national/news/video-syria-debate-brian-becker-06-15-2012.html