The pattern was familiar. Following the identification of the Boston Marathon bombers, US media were awash with experts, explaining the appeal of Jihad in Muslim communities. Security forces were deployed in major metropolitan areas. Returning from Pakistan a week after the attacks, a Homeland Security officer at JFK Airport asked me how often I pray, as though, because I’m South Asian, I must therefore be religious.

I could go on. Ask any North American American of Muslim background, and they’ll give you the same answer. There’s something farcical about it all. Instead of using the opportunity to actually learn something about Islam, Americans are taught to fear its adherents more, as though the religion is itself were a form of terror. Very rarely, or so the complaint goes, do Americans ask why Muslims embrace militarism. Most specifically, the form embraced by the Boston Marathon bombers: Salafism.

The Tsarnaev brothers are the latest incarnation of a growing social problem. Often, in the face of growing Islamophobic sentiment in North America and in Europe, left-leaning Westerners feel the need to downplay the appeal of terrorism in Muslim communities. Much of this is well-warranted, as Salafi militarism remains a fringe movement, and is often publicized for xenophobic reasons, rather than the security threat that the ideology actually poses.

However, it is equally true that there are young Muslims who grew up in Western countries, who view Salafi militant organizations with sympathy and affection. Intelligence agencies have some reason to see the Tsarnaev brothers as only one manifestation of an overall trend. It is one that includes the assassinated al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula leader Anwar al-Awlaki, who was born in Las Cruces, New Mexico as the son of a Fulbright Scholar, and who studied engineering at Colorado State University.

The bloated field of security studies that was spawned by the War on Terror has yet to provide an answer as to why this is happening, let alone how to solve it. This is part of the reason that homegrown Islamic militarism has become an American obsession. But the reason that security studies is unable to assess this issue is because the field tends to over-emphasizes the importance of non-state violence. This makes it next to impossible to analyze why some young Muslims become terrorists without first understanding Salafism’s appeal.

Salafism is a complicated movement of revivalism that began in the 18th and 19th centuries. It seeks to emphasize the Islamic scriptures of Qu’ran and Hadith that are associated with the Rashidun Caliphate. The love for this period in Islamic history is based on a Sunni mythology of its four Rightly Guided Caliphs. It is believed that the Caliphs ushered in a golden age for the young Muslim community that was marked by justice, prosperity, and perhaps most importantly, military strength. Understanding that they have to accept certain elements of modernity, the many groups that spring from the movement attempt to use various methods in order to establish the Rashidun Caliphate under modern conditions.

It is fairly easy to understand why this idea became popular when it did. The Rashidun Caliphate became hailed for its piety and strength during a period when Muslim-dominated areas of the world were grappling with the consequences of European imperialism. The bloodshed directly correlated with a faith in the Rashidun in order to heal the past and prevent more instances of the violence.

There have been a number of recent changes on these models, most notably that many groups (such as the Deobandi movement) now have a source of funding from Saudi Arabia. Salafism remains a reaction to colonial and post-colonial violence. Especially after two bloody wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and taking into account other neoliberal characteristics such as financial crises, ecological devastation, and rampant consumerism, Salafism holds a great deal of appeal in Muslim communities throughout the United States and Europe.

This is the ideological precondition for youth joining terrorist outfits that brandish a post-modern definition of jihad intent on reviving the Rashidun. Salafism, as it is practiced in most communities, is actually apolitical. This is primarily because Saudi Arabian Wahhabism focuses on ritualistic aspects of Islam in order to discourage religious movements against the country’s monarchy-theocracy. However, many young people become frustrated with this apathy, which is seen as being inadequate to ending the humiliating relationships of violence that continue to dominate their relationships with Europe and North America.

The Tsarnaev brothers are proof that this is often felt amongst Muslim immigrants, which, in the United States is already burdened with an invisible pressure to perform its whiteness to ensure its integration. Since September 11th, Muslim communities have had the additional expectation to publicly distance themselves from terrorists. This has often meant ensuring that other Americans do not perceive them as threatening, which has become increasingly difficult and anxiety-provoking due to a rise in Islamophobia. It is not at all difficult to imagine why the possibility of a mythical Rashidun free from these and other struggles would have an appeal to the minority of Muslim youth that take it seriously.

Journalists such as Glenn Greenwald have written that the irony of the War on Terror is that the strategies purported to be essential for its victory end up creating exactly the conditions for it to be prolonged. Certainly, the fact that the Tsarnaev brothers are stated to have been self-radicalized by the U.S.-led occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan agree with that assessment.

We must also remember, though, that for many radicalized Muslims who grew up during the War on Terror, these occupations were merely an indication of wider political failures in North America and Europe, which has little to do with Islam, or the Middle East. Taking up arms against the West is just another chapter in opposing imperialism (or post-imperialism, as it were,) in this case, in the guise of neoliberalism.

The mythology of the Rashidun is not simply an objective for Islamist state building similar to the Islamic Emirates of Afghanistan, Somalia, Timbuktu, and so on. It is also an idolization of a period in Islamic history that Salafi rhetoric regards as separate from history itself. The Rashidun has become seen as a vaguely paradisiacal epoch of social organization that stands in direct contrast to the uncertainties and brutality of modernity. The desire to realize it through violent means should therefore be read as a desperate attempt to break current trends of history in favor of something else.

For many Salafi Muslims, a return to the Rashidun is actually a collective reincarnation. It would constitute an ethical renaissance in an Islamic world still mired in conflict with Western governments. Many Salafi terrorists, including radicalized Muslim youth, see themselves in service of this mission. In my view, the only way to fully tackle this problem is to embrace the best aspects of the Arab Spring, meaning those formulated by the leftwing of the rebellion – labor unions, and pro-democracy advocates, in particular – to help create a new social order in the Muslim world.

Certainly, if rebuilt according to the dictates of such a left, the conditions that inspire Salafism would be significantly reduced. Including those that inspire its adherents in the West, who look towards the worst aspects of the Levant, for their inspiration.

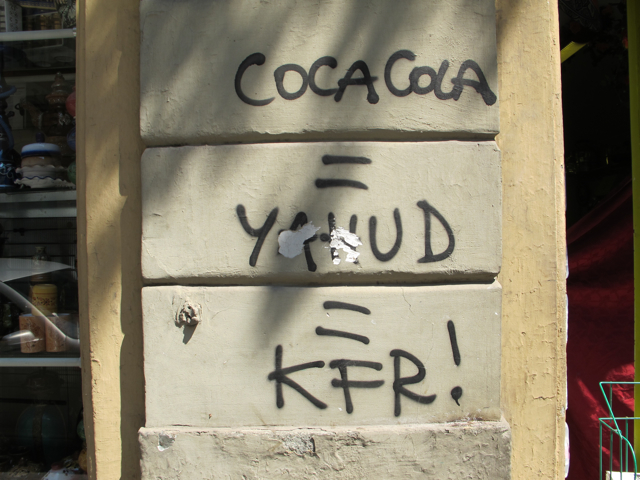

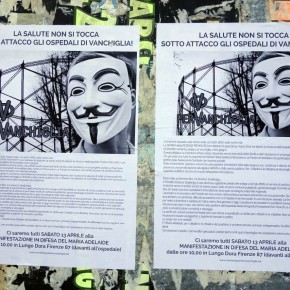

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit