Leftists often bemoan a perceived lack of progress on the issues they work on. Fighting economic injustice, war or discrimination can feel like a thankless task. On top of the difficulty of the work, too often we fail to celebrate success and lose a longer historical view of how the world has changed for the better.

That’s why this week’s revelation by National Basketball Association veteran Jason Collins that he is gay is so important. Collins is the first professional player in a major US male team sport to come out while he was still active, and the media as well as most other athletes who have spoken publicly have been extremely supportive. It’s worthwhile to stop and realize that only a few short years ago the response would have been very different.

As an avid athletics fan who often listens to sports talk radio, I can say that the worst of the responses I’ve heard have been measured and usually consist of asking “why does he even have to bring it up?” That is a very long way from the open hate directed at Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered (LGBT) people that I’ve heard most of my life, in every social realm. Still, it’s worth examining just why it is so important that Collins came out publicly.

The fact is, statements and stances by public figures can have a strong impact on people who are struggling with their identity. It’s a terrifying way to live when you are hiding who you are and afraid of what those dear to you might think if they found out. That is an experience I know too well. And it leaves one very vulnerable to the actions, both positive and negative, of famous people who dare talk about “it.”

By the age of nine, I knew I was bisexual, even though I couldn’t articulate that idea even in my own mind. As I got older and moved into my teens, I grappled with shame, denial and an overwhelming fear of discovery. Though actively bi from the time I was 14, I didn’t tell anyone, not even friends who were gay, let alone my family, until I was 26.

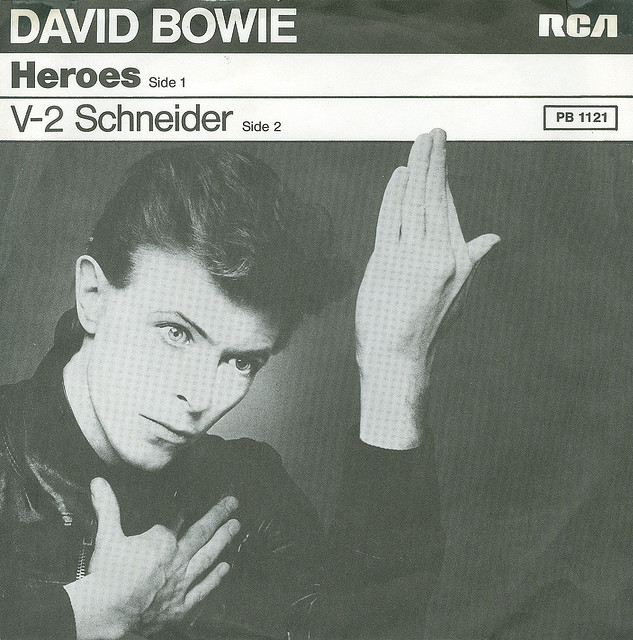

One of the things that got me through those difficult times was my favorite (to this day) musician, David Bowie. I had been listening to Bowie since I was nine, and didn’t really get the whole bisexual thing about him until I was twelve or thirteen. That was, as it turned out, just when I needed it the most.

I wasn’t sexually active yet, but I always felt that my interest in guys showed, even though I could honestly display a genuine interest in girls that was just as strong. I felt like people could read my “inner queer.” My environment was split between a religious Jewish community and a lot of hormonal teenagers, some of whom liked to get drunk and talk about “going to beat up some fags,” so external pressure reinforced internalized homophobia to make me feel alone, afraid, and ashamed.

But Bowie put another feeling inside me, one of pride and a sense that this brilliant artist was just like me, at least in one way. I waited for a new album with great anticipation (even when he was in his Berlin phase and I was too young to grasp the music I would later recognize as his most brilliant work). I loved Bowie’s music before it related to my struggle to accept my sexual identity, but he later came to be the one support I felt I had for that struggle.

Then, after 1980’s Scary Monsters there came three years of nothing, very little new music, as Bowie struggled with putting his life back together after overcoming drug addiction. Finally, in 1983, Let’s Dance came out. I was 17 that year, and I waited for that record as I had the previous four. The record was a hit, probably Bowie’s most successful ever in the US. But I was bitterly disappointed. It lacked any originality or creativity. Let’s Dance was just a very well-produced pop LP. And then came the really devastating moment.

Bowie gave an interview to Rolling Stone, and the cover blared out loud: “DAVID BOWIE STRAIGHT!” Bowie told the magazine that his public declaration of bisexuality was “the biggest mistake I ever made” and “I was always a closet heterosexual.” I was devastated.

It wasn’t only Bowie. In 1983, AIDS was really making its way into the headlines and hatred of gay men was rampant. Much of the progress that had been made since the 1960s’ gay liberation movement was being reversed. The gay culture that was so open during the Decade of Disco was being forced back underground under the cloud of a devastating epidemic. Worse for me, bisexual men were seen as the “conduit” the “gay disease” was using to infect heterosexuals.

It was a tough time to be anything but straight. For the next decade, I watched as friends and, later, colleagues got ill and died. And the one thing in my life that had once made me feel positive about my sexual identity had turned its back on me, told me it was all just a publicity stunt. I had, in 1983, been considering sharing my bisexuality with some of those closest to me – my best friend, who was a lesbian, my brother, one or two others I thought might understand – but I was already terrified, and Bowie’s reversal slammed that idea deep down for almost a decade.

David Bowie continued his artistic decline through the 1980s, culminating in the perversely titled Never Let Me Down. For me, his meaning in my life had disappeared and so did his music, leaving me with only the records of the past, which, though I still loved them, now seemed like mere illusions.

In 1990, I found a book of short stories by a wonderful gay, Jewish writer named Lev Raphael. In it was a story called “Betrayed by David Bowie,” which made be weep for hours after I read it. Raphael wrote about his reaction to the Rolling Stone interview:

“I couldn’t buy the new album. I waited for Bowie to clarify, to say that he wasn’t denying his past, that this was all just some kind of intriguing retranslation of himself, like Ziggy (Stardust) or Major Tom. I wrote angry letters in my head. Bowie was more popular than ever before and his music was the least original of his career. He was claiming to be just like everyone else; forget about ‘Queen Bitch’ or wearing a dress or going down on Mick Ronson’s guitar at more than one concert, or singing about trade, ‘a butch little number,’ cruising, ‘the church of man love’ being ‘such a holy place to be,’ all of it, the obvious and the metaphorical. ‘The Man Who Sold the World’ was selling himself and everyone who’d believed in him.”

Raphael’s words mirrored my own feelings. But I also knew that Bowie didn’t owe me anything. He would manage his own life and career as he wished, and that was his right. Eventually, I found my own way to come out to those closest to me. Some of it wasn’t easy, and some reactions were very unpleasant. But mostly, I found acceptance and warmth and love.

What does this story have to do with Jason Collins? A lot. Somewhere out there, by the hundreds, are young men and women who love basketball, who are also gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgendered. There are other gay athletes, but a man in one of the major team sports in the US has now broken that barrier and come out while he was still in the league. Some of those kids will be more able to be open about who they are now, and some who still aren’t ready to do that will find some comfort in Collins’ revelation.

And it’s important for us all to realize that 2013 isn’t 1983. About a decade ago, David Bowie, who since his comeback in the mid-90s has again produced some of the most brilliant and creative music in the world and seems (with Bowie, one can never assume what’s real, only what seems to be) to have shed his various personae and decided to just be David Bowie, revised his stated sexuality again.

In an interview with Blender, Bowie was asked if he still thought saying he was bi was “the worst mistake” he ever made.

“Interesting,” he said. “I don’t think it was a mistake in Europe, but it was a lot tougher in America. I had no problem with people knowing I was bisexual. But I had no inclination to hold any banners or be a representative of any group of people. I knew what I wanted to be, which was a songwriter and a performer, and I felt that [bisexuality] became my headline over here for so long. America is a very puritanical place, and I think it stood in the way of so much I wanted to do.”

I felt better, not least because I shared Bowie’s view of the US and still do. By that time I was at peace with myself, and comfortable with who I am. But more importantly, Bowie’s ever-present marketing sense reflected a changing world. The US was lagging behind and still is, but even here, times have changed and changed radically.

The response to Jason Collins is as solid proof as you’ll get. It’s a lot of hard work and difficult times, working to make the world a better place for everyone. We sometimes take a step or two backwards, but we can change the world. We’ve done it before, and we’ll do it again.

Photographs courtesy of Affendady. Published under a Creative Commons license.