Barack Obama continues to insist that surveillance of telephone and internet communications is necessary. Speaking in Berlin, where the outcry over PRISM has been the loudest amongst US allies, Obama claimed that the surveillance had thwarted “at least 50 threats of terror attacks in the United States and other countries,” according to the Voice of America.

National Security Agency Director Gen. Keith Alexander told a Congressional hearing the same: “In recent years, these programs, together with other intelligence, have protected the U.S. and our allies from terrorist threats across the globe to include helping prevent the terrorist — the potential terrorist events over 50 times since 9/11.”

The statements conjure images from the classic Red Scare-era classic, The Manchurian Candidate. In that film, a US Senator, being manipulated by his Communist wife, hurls accusations of Communism everywhere and bolsters his case by waving a piece of paper he says is a list of known Reds in Congress. The number of names on the list changes with each mention. Obama’s and Alexander’s claims have the same credibility.

The case Obama and his administration are making is that we should trust them, because they are charged with our safety, and, while they may have to take some unfortunate measures to fulfill that charge, they have only the best of intentions and will keep intrusions to a minimum. There is some truth to that, but few indeed are the Americans (and even fewer outside the US) who are willing to simply trust that the United States government will pass up on information it can easily obtain under the guise of security in order to maintain our civil liberties.

History teaches us the lessons we need to learn here about the respect of our government for democracy and, by extension, privacy. When it comes to security, there is no greater decision that can be made by our government than whether or not to go to war. Even in cases where the President is authorized to unilaterally deploy US forces, he must consider the political ramifications very carefully. The political consequences of bringing US forces into combat on a large scale against the will of the people can be grave.

So what happens when a President makes that calculation, realizes that he does not have the political backing he needs to go to war, but wants to anyway? He lies to convince people to follow his decision. As bad as that sounds, though, there are scenarios where it might be defensible. Three historical examples are useful in framing the question.

In 2003, neoconservative forces, aligned with Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, had defeated more mainstream conservative forces represented by Secretary of State Colin Powell and were setting the course of US foreign policy. They wanted to invade Iraq, secure its resources for US interests and plant a friendly government in a key state on the Arab side of the Persian Gulf. But there was no proximate justification for the war. So, they manufactured one.

At first, in speech after speech, President George W. Bush cautiously avoided any claim that Iraq had any connection to the attacks of September 11, 2001, but his speechwriters always put mention of Iraq and al-Qaeda very near each other, building an association between the two. After a time, the case became more explicit. Needing more to push the US into a second war in the region, the Bush Administration hammered away at the idea that, despite the fact that UN inspections confirmed that Iraq had no “weapons of mass destruction,” Iraq had managed to secretly make and conceal such weapons.

Bush created evidence, such as falsifying “proof” that Iraq had attempted to purchase “yellowcake uranium” from Niger. He sent the defeated Colin Powell to the UN with an embarrassingly absurd scenario of mobile high-tech weapons labs in trucks, a story that would have been laughed out of the worst James Bond script. But, in the end, Bush was able to hammer away sufficiently to convince enough of the US public to support the invasion of Iraq. We will paying dearly for that action for years to come, though not nearly as heavy a price as Iraqis and others in the region.

Bush, in 2004, after it was clearly established that there were no weapons of mass destruction and no connection to 9/11, said: “Knowing what I know today, we still would have gone on into Iraq. We still would have gone to make our country more secure. He had the capability of making weapons. He had terrorist ties. The decision I made was the right decision. The world is better off without Saddam Hussein in power. And I find it interesting, in the political process, that some say, well, I voted for the intelligence, and now they won’t say whether or not it was the right decision to take Saddam Hussein out. It’s the right decision, and the world is better off for it.”

Forty years before Bush uttered those words, another Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, decided the President did not need to know that a report of an ambush of an American destroyer in the Gulf of Tonkin was not correct. Lyndon Johnson, the president at the time, certainly was eager to expand the war in Vietnam, and when informed of the “ambush” had set about making plans for obtaining Congressional approval for that expansion. In the end, Congress gave him the resolution he wanted, and the American presence in Vietnam started to swell rapidly.

It may well be that LBJ would have pursued the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution even if McNamara had told him the whole truth. Indeed, the record remains somewhat inconclusive as to what Johnson knew or suspected and when he knew it, though it seems clear that he did eventually figure out what McNamara had done and didn’t inform Congress, much less the public, of the deception. In any case, the US public did not know until later that the turning point in the escalation of the Vietnam War was a congressional resolution based on an incident that US leaders knew had not occurred.

This is the government that is today asking not only its own citizens, but the entire world to trust that, while it might have the ability to spy on everyone and is running a program to enable it, it respects democracy and privacy and will only look at the information it is gathering when absolutely necessary to save lives. It is also asking us to trust it when it runs such programs without ever telling the public and allowing for debate on whether or not we want such a program or are willing to extend such trust.

Obama might have been able to make a case in support of all of this surveillance, though it is pretty likely that a clear majority of Americans would have opposed it, despite the fear we live in today. That fear was just as strong regarding “Commies” in the early 60s, and even more acute just a few years after 9/11. But in all of these cases, we note that the assault on civil liberties uses the fear of the current demon – first Communists, now terrorists – to accomplish its goals.

Yet, we can also see where sometimes the tactics are vindicated. In 1940, Franklin Delano Roosevelt led a strongly isolationist United States, but he believed that it was crucial that his country get involved in World War II. He campaigned on a platform of keeping the US out of the war, while simultaneously working to provoke Japan and Germany and gradually step up US involvement well before the attack on Pearl Harbor at the end of 1941. There can be little doubt that FDR willfully misled the American people and stealthily acted against their will.

This last incident demonstrates that sometimes, secrecy can be necessary. Historian Howard Zinn did an important service in offering a different framework for understanding World War II. Yet even Zinn cannot make the case that it wouldn’t have made any difference if the Axis had won, nor that such a victory would not have come about if the US had delayed its entry long enough for Britain and Russia to fall.

While FDR’s actions tell us that we need to seriously consider the issue of secrecy, the experiences of Vietnam and Iraq, and how easily lies led the country into both, must make us all the more skeptical of a government that is asking us to trust that it is only treading on crucial personal rights when it absolutely must. And certainly it should prevent us from taking the notion that “fifty terrorist attacks” were prevented by the surveillance programs at face value. We should believe that when there is evidence to support the claim. And then we will need to ask if that means it was worth it.

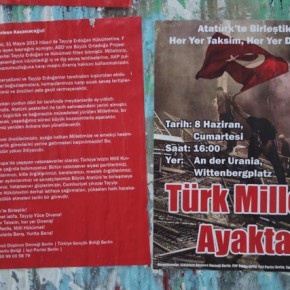

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit