One of the peculiarities of punk is that its ethos of personal freedom has often been expressed through regimentation. Punk’s earliest exponents had no coherent ideology, yet punk exists today as a congeries of well-defined styles and symbologies. A further feature of its history, whose appearance was roughly coterminous with the emergence of punk itself, is the view that punk is dying or that it is already dead.

The two things are not unconnected. Punk, a cultural formation whose basic impulse is the search for the new, to fight boredom, is constantly looking backward to a more vibrant past. Yet, paradoxically, these repeated cycles of destruction and sclerosis are not a sign of degeneration, but rather an expression of a vibrant process of re-appropriation, one that goes some way to explain why punk and its stylistic progeny persists in the present day.

One of the most important moments in the early development of punk occurred during its transition from North America to the United Kingdom in the mid-1970s. There was no stylistic continuity, either in music or dress among the various scenes in cities like New York, Detroit, and Cleveland. With the possible exception of track marks, nothing united the disparate groups outside of their orientation to settled middle class culture. When punk caught on in the UK, it quickly synergized with the clothing style-based youth cultures that already existed in the country.

In an interview with the documentarian Don Letts, Joe Strummer once summed up the significance of clothing style in the early UK punk scene: “I know in America people think it’s ridiculous that people can fight to the death over articles of clothing, but in these islands it’s a different story.”

Youth groups such as the mods were an outgrowth of the postwar boom in Great Britain. The mods originated in the late 1950s, in a time when expanded employment opportunities for young people meant that they could afford to buy tailored suits and jazz records. In the fluid cultural milieu of postwar Britain, mod culture was eventually co-opted commercially, but it also fragmented, giving rise to further clothing based cultures like skinheads and teddy boys. This latter group comprised fans of jazz and skiffle and who attired themselves in suits that recalled Edwardian styles of dress.

British punk was always likely to have a strong sartorial dimension, given that two of the scene’s most important progenitors of the scene were the fashion entrepreneurs Malcom McLaren and Vivenne Westwood. McLaren and Westwood had run a series of clothing stores on the King’s Road in London, a central nexus between fashion and youth culture in the 1970s. The teds were experiencing a last hurrah of sorts in the mid-1970s, when punk came on the scene in Great Britain. As Strummer noted later, the punks reconfigured the teddy boy style to express their own brand of apocalyptic social criticism. “Punks took [teddy boy jackets] and tore them up and put safety pins through them. [Johnny] Rotten was particularly good at decorating a jacket.” While the redeployment of teddy boy style was not the only element of early punk fashion, it constituted a significant enough element to spark a severe outbreak of intercultural violence between punks and teds in 1976-77.

The conflict between the punks and the teds, although intense, eventually petered out, both because the atavistic teddy boy culture was in decline and because the punk subculture itself was changing. By the late 1970s, the original cultural impetus of punk was dying. Most of the early punk bands had split up or gotten signed by major labels, illustrating the degree to which the punk of the time was unable to differentiate itself from the established music cultures out of which it grew. The process of cultural ossification proceeded apace. Whereas punk style in the 1976-77 had been a relatively freewheeling proposition, in which adherents could define for themselves what the punk look comprised, by 1979-80 black motor cycle jackets and boots (whether Dr. Martens, engineer boots, or simple combats boots) had coalesced into a stylistic form that would define the punk look for most of the 1980s.

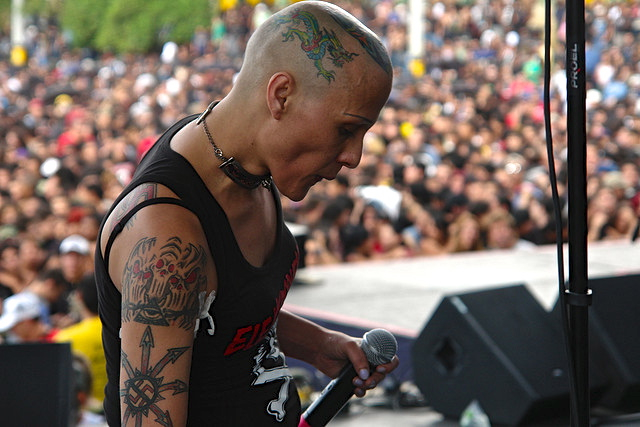

The last days of the 1970s saw the rise of a new generation of punk music that would shape the so-called hardcore punk scene (sometimes just shortened to hardcore.) Bands like Discharge, Chaos UK, and Disorder defined both the look and the sound of the new wave, with simpler, more aggressive music and the black leather style of the latter days of the original English. punk scene. This particular stylistic mode expanded and transformed, both in the British heartland. but also as the hardcore scene spread into Scandinavia. Additions to the stylistic cannon included that addition of metal studs by the hundred, which added to the implication that the punks of the early 1980s hardcore scene were some sort of post apocalyptic warrior. It also expanded to include painted designs, sometimes merely band names, both other times quite ornate renditions of records covers and other iconography. In a way this recalled, and was an expansion of, the Lettrist impulse that had shaped the early style of The Clash.

It is important to note when talking about these styles that these are generalizations, not universals. As the hardcore form diffused, creating micro-scenes around the globe, it brought with it complex processes of creativity and conformity. Much depended on exactly what the means of transmission was; which records, which fanzines, which videos penetrated where. As hardcore punk spread to rural America, a wide range of stylistic influences could be seen. Large cities tended to allow for more rigid stylistic definition. Penelope Spheeris’ 1983 punk period piece Suburbia illustrates this point. Set in the Los Angeles suburbs, the characters (most of whom were actually recruited from the ranks of the LA punk scene) reflected a wide range of stylistic influences, while still recognizing each other as part of a common culture.

This element of recognition was crucial. As punk spread, forming small pockets in the vast expanse of the exurban United States, the need to represent intensified, serving both to discomfit normal people and to facilitate recognition by those similarly inclined. Unmoored from the original emergence of punk in the US in the early 1970s, the hardcore kids of the 1980s mixed and matched often quite disparate elements, creating a styles that both reflected elements of earlier stylistic movements and hybridized them in ways that reflected the availability of certain kinds of clothing (flannel shirts, trench coats, and other items likely to be found at the local Goodwill or St. Vincent DePaul.) They created their modes of expressing the marginality of disaffected white, suburban, youth that appropriated earlier developments, sometimes playfully, sometimes expressing the urge to uniformity implicit in the need to create boundaries for the disadvantaged.

By the mid-1980s, the British scene had further transformed, in part with the interpenetration of the hardcore scene with political anarchism. The bands that made up the hardcore, crust, and grindcore communities in the UK lived a marginal lifestyle in the high unemployment environment of Thatcher’s Britain, subsisting on dole allotments and living either in council housing or in squats. Although some stylistic elements were retained (for instance the motorcycle jacket was still a common accoutrement,) the combination of penury and the increasing influence of animal rights politics wrought important stylistic changes in the punk scene.

One important result of this was a change in tendency from dressing in motorcycle gear to simply dressing in rags, thus emphasizing one’s disenfranchisement from the dominant culture. The black leather jacket type of punk style turned out to be a relatively easy target for appropriation. Dirt and raggedness proved less apt for such purposes. Bands like Chaos UK (who had been original proponents of the black leather jacket style,) as well as newer acts such as Concrete Sox, Amebix, Antisect, Doom, and Extreme Noise Terror brought this style to greater prominence as the profile of their music rose.

Photographs courtesy of Telemedellín – Aquí te ves, Paul Townsend Helgeov and ♪♫PSICO–MOD♪♫. Published under a Creative Commons license.